Columbus’s connection to Lisbon was significant but complex. He resided in Lisbon for nearly a decade (from around 1476), joining a colony of Genoese merchants and working as a mapmaker alongside his brother Bartolomeu. He first learned to read in Portuguese

Lisbon, then the world center for navigation, was where Columbus gained crucial nautical training, learned from ongoing Portuguese Atlantic exploration, and married the Portuguese noblewoman Filipa Moniz Perestrelo. This milieu profoundly influenced his development as a navigator and inspired his westward Atlantic ambitions. In spite of recent blame for the violence of Spain in the conquest of the Americas and removal of a USA holiday held in his honor, Columbus remains an inspiration to US sailors.

US Sailors who cruise are different than those who just race. A US pure racing sailor views sailing as a competition between human athletes with the vessel being equipment. A US cruising sailor views the crew as components of the vessel required to make it seaworthy. These views have implications in crew selection and training.

The former allows for selection of athletes who have no sailing experience (but are otherwise fit for a triathlon). These follow without knowledge necessary to form questions. Those who do not venture to ask questions are valued over those who do. Knowledge is shared on a need to know basis because there is concern that selected athletes may take knowledge to competitors. Knowledge of the racing rules isn’t desired because loyalty is valued above the competency gained from study of the rule books. The athletes are replaceable – meaning they can be flicked off (removed from) crews with no damage to the overall goal -which is to win.

The later US Sailors, the ones who cruise, are different animals. They must seek knowledge, not just from rule books but from libraries and from scuttlebutt. They must question everything in order to gain competency and make the vessel seaworthy. This is because, on any given day, the least experienced among the crew may need to make a decision necessary for safe operation of the vessel. There may not be time to consult and if there is the captain may not have all the facts in which to make a good decision and those factsl come from the knowledgeable. If a crew member is flicked off, there is damage to the overall goal which is seaworthiness.

I thought about these points upon news of Vestus Wind’s return to the Volvo Ocean race. The restored race boat has been transported to Lisbon but her navigator has been removed from her crew, apparently taking blame for a grounding earlier.

Portugal is a nation steeped in maritime history. I advise any sailor interested in the development of seamanship and racing to make a pilgrimage to this beautiful and enlightening place.

Praca do Comercio

My pilgrimage started at the grand maritime entrance to Lisbon (Praca do Comercio) where, in 1493, a person could spend the entire day without hearing anyone speak the native language. Such was its importance in trade. Columbus announced the discovery of his first voyage, in February 1493, first in Lisbon and news of the discovery spread throughout Europe from Praca do Comercio. Columbus had strong ties to Lisbon.

Lisbon had a large Italian population from Geneva when Columbus lived and worked there as a cartographer with his brother. He later was given a library from his wife’s father. Portuguese was the language of navigation while Columbus was alive and when it was time for him to learn to read (at age 25) he excelled in reading navigation books. It was clear to any who could read that the world was round and hence it is useful to ponder why the myth of a flat world was held so dear.

Need to Know Knowledge Sharing supported Flat world Myth

In 1492, a crusade had just ended in Europe, which was recovering from loss of life owing to war and plague. Coastal populations in Portugal struggled with Barbary Coast pirates who gathered slaves from those populations for trade in Arabia and for ransom.

Venetian merchants held a monopoly on trade with India and China because they were willing to work with Moors and were ruthless in protecting the routes over land. Knowledge of these routes was worthless without consent from the Venetians because anyone attempting such land based trade would be executed unless permission had been given. It was a strong monopoly.

The Military Order of Christ (successor to the Knights Templar in Portugal) knew that a sea trade with India and China was possible by following the coast of Africa. Their Grand Master (today known as Prince Henry the Navigator) spent 40 years and considerable Order of Christ wealth in trying to break the Venetian monopoly.

Rumors such as the world being flat but also rumors involving the lost city of Atlantis and sea monsters helped the Venetians hold on to their monopoly. Half of the sailors Henry sponsored died on expeditions so, even without rumors the risk was high and reward not certain until 1445 when numerous captives could be obtained past Cape Bojador.

The Importance of Libraries

Prince Henry, by agreement with his older brother Pedro (who was regent to the child-king Alonso V), received a charter for one-fifth share of all profits from African voyages that normally went to the crown. Substantial profits from the slave trade financed further day trips down the African coast. With the opening of the first slave market in Europe in Lagos Portugal, traders found it profitable to lease the charter from Henry until Prince Henry’s death in 1460.

Columbus was a boy about 10 years old when Henry died but he had already begun work as a sailor out of Genoa, Italy on vessels that visited Lisbon, England, and Flanders. During one attempted visit, in 1476, his vessel (part of a 5-boat convoy) was mistakenly identified as a Barbary Coast or other enemy vessel and was destroyed by Portuguese defenders.

Columbus survived by swimming to the site in Sangres where Henry the Navigator is credited with having founded a school for navigation. Columbus considered this his lucky career break, quickly making Lisbon (where a large Genoese colony was established and his brother worked as a map maker) and then, after marriage, Madeira his home.

His first child was born in Porto Santo of the Madeira Islands which is 600 miles off the coast of Portugal. You can visit what is claimed to be the Columbus home today at Porto Santo. His wife’s father, Captain Bartolomue Perestrello , the governor of Madeira, had passed away when Christopher Columbus married and his mother in law gave Columbus the Captain’s library. When his wife died (five years after their son was born in 1485) Columbus focused on financing a voyage across the Atlantic. In most ways Columbus was at this time Portuguese and not Italian.

Portuguese focus on breaking the Venetian monopoly, lost after Prince Henry’s death, was renewed by the time Columbus pitched his voyage to the King of Portugal (Prince Henry’s grand nephew.) The king was not interested in such a voyage because of knowledge that breaking the monopoly was possible simply by continuing the focused day trips Prince Henry had supported down the African coast. Each explorer was required to plant stone markers, called padroes. And by contract, a padro had to be placed beyond all predecessors.

It would be just a matter of time until markers extended to India and beyond. Columbus pitched his proposal many times to King Joao and to others eventually finding – after six years of rejection – acceptance by Queen Isabella of Spain, some think owing to the two both having red hair in common, but others believing that promise of new lands to be given to Military Order of Christ members, of which Columbus was one, were needed now that a crusade in Europe had ended.

The symbolism of hair color in nobility has deep historical roots and varies greatly across cultures and periods:

- In ancient Egypt, darker hair shades often symbolized nobility and higher social status, while lighter or reddish hair, often dyed with henna, was associated with vitality, youth, and divine favor (e.g., red hair linked to goddess Isis)14.

- In ancient Greece and Rome, blonde hair was strongly admired and associated with divinity, heroism, and beauty, often depicted on gods and noble figures. Roman noblewomen used dyes to achieve blonde or reddish hair, marking class distinctions—red being preferred by the elite and lighter hair associated with higher status. Conversely, darker hair colors were more common among lower classes2348.

- During the medieval period in Europe, blonde hair symbolized angelic innocence and purity, while red hair became linked to supernatural traits such as witchcraft or fiery temperaments, sometimes stigmatizing red-haired individuals amid witch hunts. Yet in places like Scotland and Ireland, red hair was a proudly celebrated Celtic trait3456.

- Hair color also had legal and social class implications—for example, in Roman times, prostitutes were required to have blonde hair to signify their profession, while other classes adhered to specific hair color norms29.

In summary, hair color symbolism in nobility evolved through:

- Associations of dark hair with nobility and spiritual power in ancient Egypt.

- Blonde hair as a divine, noble, or pure trait in Greek, Roman, and medieval European cultures.

- Red hair with ambiguity, esteemed in some cultures (Celtic) but linked to witchcraft or supernatural suspicion in others.

- Hair color serving as a marker of social class, profession, and identity especially in classical and medieval Europe.

Thus, the origins of hair color symbolism in nobility reflect a blend of cultural values, religious beliefs, social hierarchy, and regional interpretations across history12345.

Queen Isabella I of Castile is historically described as having hair color that ranged between strawberry blonde and auburn (reddish-gold). Some period descriptions and portraits show her with golden or light reddish hair, although many surviving artworks portray her hair darker likely due to pigment fading over time. As for Columbus’s hair color, historical sources are indirect and somewhat inconsistent, but several contemporaries and early portraits suggested he had light or reddish hair, which turned white prematurely.

The Italian historian Bartolomé de las Casas described Columbus as having a “reddish or fair complexion and freckled skin,” and his son Ferdinand Colón referred to his father’s hair as “light in color” before it turned white. However, there is no contemporary color portrait of Columbus, so this description is not absolutely confirmed, but most scholarly references agree he likely had reddish or auburn hair in youth.

In 1492:

- Spain was still a dynastic union, not a consolidated state. The Crown of Castile and the Crown of Aragon kept separate parliaments, laws and coinage1819.

- Navarre remained an independent kingdom north of the Pyrenees until its gradual incorporation (1512 – 1524)20.

- Granada had only just been annexed; the Canaries were still being subdued; the Kingdom of Portugal was fully independent.

- Overseas holdings (Canary Islands, later the Americas) lay outside the peninsular frontier established on period maps such as the Iberian Peninsula 1491 chart20.

Without promise of new lands, squabbling among young nobles who expected the crown to pay them in land was likely. Spain needed to search for suitable land and Columbus, unknowingly, had stumbled on the solution. The Keeper of the Privy Purse for King Ferdinand, Luis de Santangel, a cultivated friend of Columbus’, was able to secure financing for the venture using that solution as a main goal.

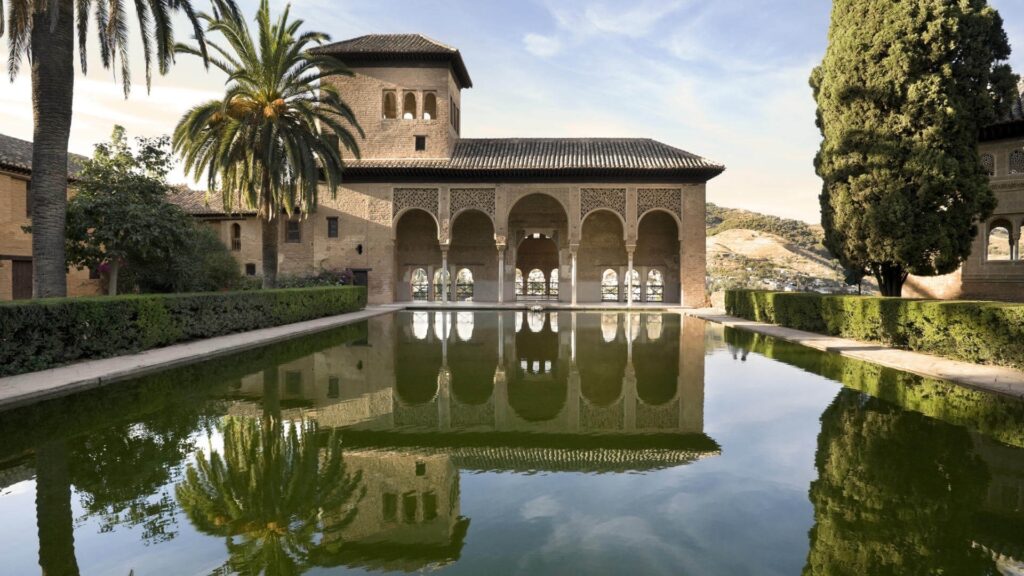

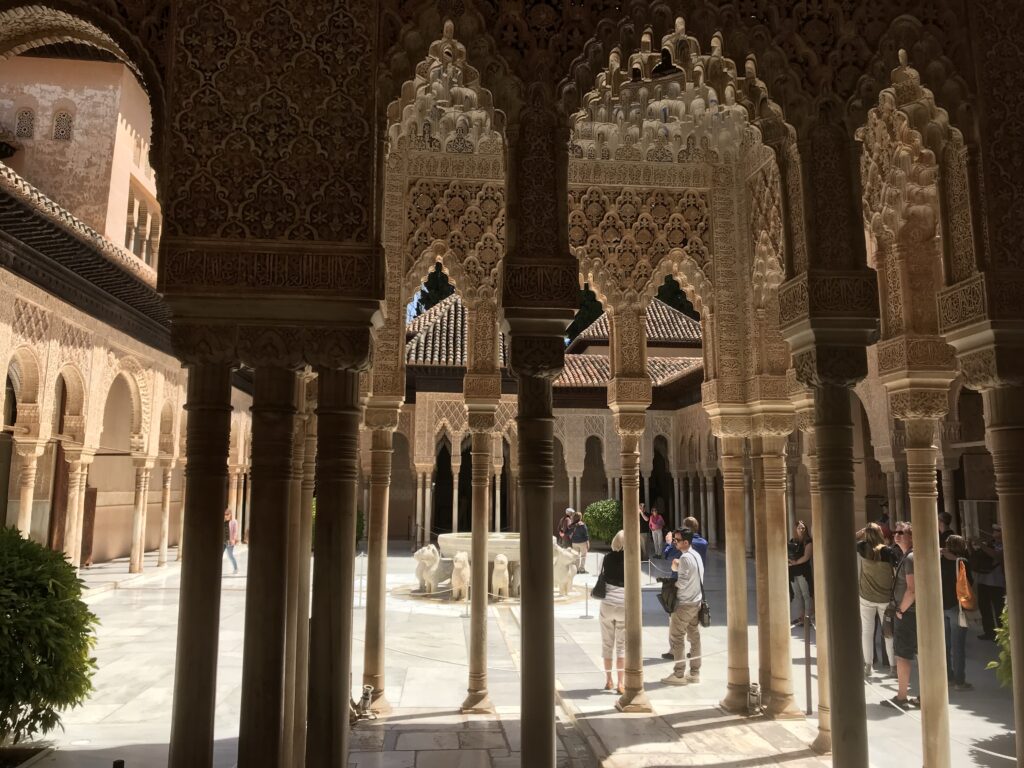

The belief that Columbus received his financing at the Alhambra comes from popular retellings rather than historical fact. In reality, the official agreement with Columbus—the Capitulations of Santa Fe—was signed in the military camp of Santa Fe, not in the Alhambra palace.

The Alhambra is often portrayed in legends, art, and later literature as the backdrop for the deal, likely because it was the main royal palace of Granada, an iconic symbol of royal authority, and the city to which the monarchs moved after Granada’s conquest. However, at the actual moment of Columbus’s contract, the monarchs were still based at their field headquarters in Santa Fe and had not yet taken up residence in the Alhambra. Santa Fe is about 13–14 km (8–9 miles) from the Alhambra in Granada.

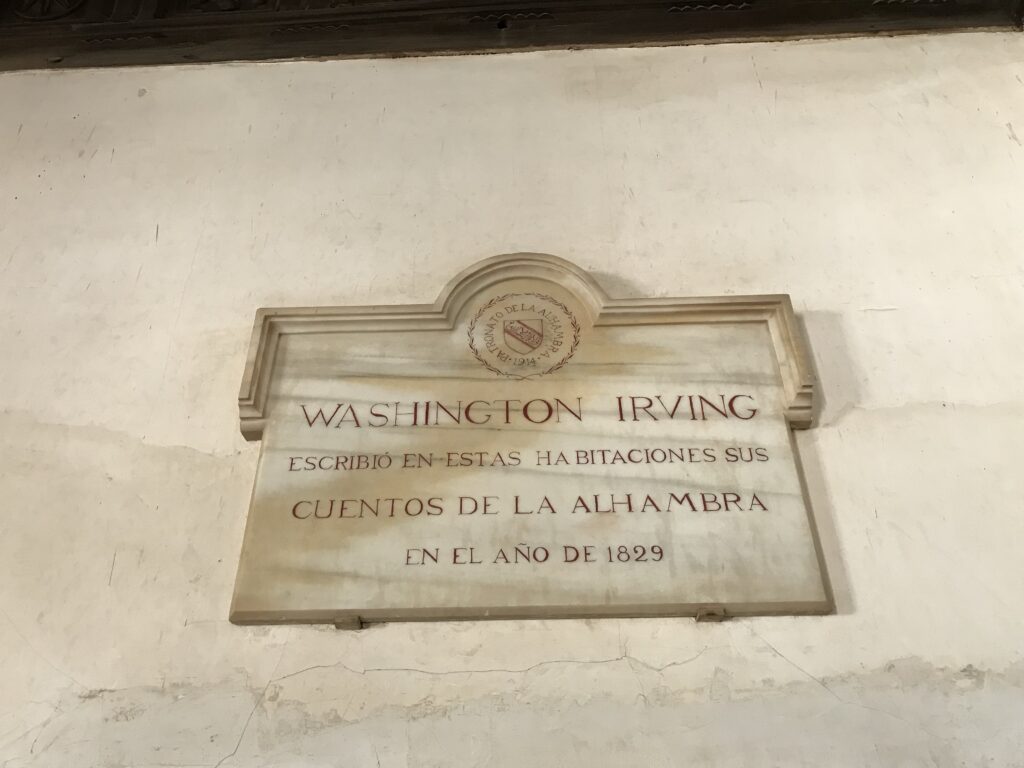

The American author Washington Irving wrote extensively about the Alhambra and about Columbus. After completing his biography A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus (1828), Irving stayed at the Alhambra in Granada and gathered legends for his later book Tales of the Alhambra (1832), blending fact, myth, and observation—this is why many wrongly associate Columbus and the Alhambra in later popular culture. A plaque in the Alhambra commemorates Irving’s stay.

The Capitulations of Santa Fe (17 April 1492) were drafted and sealed inside the royal field-city of Santa Fe, an armed camp erected during the final siege of Granada. Isabella was physically present there because the monarchs were overseeing the last act of the Reconquista; Granada capitulated less than three months earlier (2 Jan 1492) and the court had not yet returned to its usual seats. Columbus followed the army south to press his proposal at a moment when the monarchs—flushed with military success yet cash-poor—were receptive to a low-risk maritime gamble that promised revenue and religious prestige.

The funding for Columbus’s first Atlantic voyage came from a mix of royal, private, and local sources, each playing a vital role in making the expedition possible. The primary backers were the Catholic Monarchs, Isabella and Ferdinand of the Crown of Castile-Aragon.

However, the Spanish treasury was drained by the recent conquest of Granada, so the monarchs did not simply provide funds from their own coffers. Instead, the royal grant came in the form of a loan provided by the Council of the Military Order of the Santa Hermandad, arranged through the royal treasurer, Luis de Santángel. The monarchs essentially borrowed over 1 million maravedís, a formality that allowed them to back Columbus’s venture despite limited available cash.

Luis de Santángel and a group of Genoese and Florentine bankers in Seville contributed by advancing the cash needed for the expedition, expecting to be repaid later when the crown’s finances improved. Their involvement was crucial to overcoming immediate funding obstacles.

Christopher Columbus himself provided a small part of the funding, personally raising up to one-eighth of the total costs. He managed this by pledging a share of prospective profits and securing support from minor backers—he was not wealthy, and his stake relied on future returns, not present wealth.

Support also came from the town of Palos and the Pinzón brothers, who provided two of the three ships (the Niña and the Pinta) and assembled experienced crews. Their contribution served as payment to the crown in lieu of fines they owed, effectively offsetting a large part of the expedition’s material needs.

In total, about 2 million maravedís (≈ US $350 000 today) were raised for the 1492 voyage—half in cash, the rest through in-kind resources like ships, supplies, and wages. The popular story that Queen Isabella pawned her jewels to finance Columbus’s expedition is a later romantic invention; records show her jewels were already pledged to fund the war with Granada, not the Atlantic voyage. Instead, the enterprise was made possible through a combination of royal approval, financial maneuvering, personal risk, and local obligation.

Scuttlebutt

The Pinzon brothers accompanied Christopher Columbus on his first Atlantic crossing. Columbus documented concerns regarding Alonso Pinzon because Alonzo Pinzon preferred to sail the Pinta at hull speed, racing ahead of the Santa Maria, a bulky trading ship that Columbus sailed on with Juan de la Cosa serving as Captain.

When the Santa Maria was lost on a reef, the Pinta was absent and it was Yanez Pinzon on Nina that calmed the panic by encouraging the Santa Maria crew as well as Captain Cosa to follow Christopher Columbus. Captain Cosa had put the least experienced crew member at the helm of The Santa Maria when she went aground and was lost on Christmas Day 1492. As Captain, this was his right. However, Columbus had warned him against doing so.

When Santa Maria crew members were safe ashore Columbus founded fort Navidad and gathered timbers from the wreck for its fortification. On January 4th1493 he joined Yanez Pinzon on Nina, caught up with Alonso Pinzon on the Pinta, and allowed himself to be convinced that insolence and disloyalty were not involved.

A homeward passage then commenced with the understanding that both vessels would stay within sight of each other and use flares at night to make that possible. 39 men were left at fort Navidad. The passage home was eventful.

Owing possibly to storm, the Nina and Pinta were again separated and both assumed the other had been lost. Both required repairs (Nina in Lisbon and Pinto in Vigo Spain) before returning to home port in Palos Spain on the same tide.

The Nina had arrived first and Alonzo Pinzon had nothing to look forward to but inevitable charges of insubordination. He died within the month but not before disseminating some rumors about Columbus wanting to abandon the Atlantic crossing before sighting land. His brother Yanez would not support the rumors. It is likely that Columbus, by disseminating his story from Lisbon earlier, limited damage that may have been caused by Alonso Pinzon and those loyal to him.

Columbus’ instance that the Nina and Pinta arrive together was supportive of a unified communication regarding his findings.

In 2011, fado was inscribed on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

The essence of fado is captured by the word saudade, a Portuguese term for a profound sense of longing or nostalgia for something lost. Fado is performed in intimate settings such as pubs, cafés, and traditional “fado houses,” and has become a symbol of Portuguese national identity.

According to 16th-century Spanish chronicler Francisco Lopez de Gomera, Columbus’ first voyage was the “greatest event since the creation of the world (excluding the incarnation and death of Him who created it).” But his subsequent voyages were worse than unsuccessful.

None of the 39 left at Fort Navidad were found alive when Columbus returned later that year. They had all been killed by Indians. The following decade turned Columbus from an optimistic and talented entrepreneur to a pessimist obsessed with the idea that enemies were everywhere. He suffered from severe arthritis and died on May 20 1506.

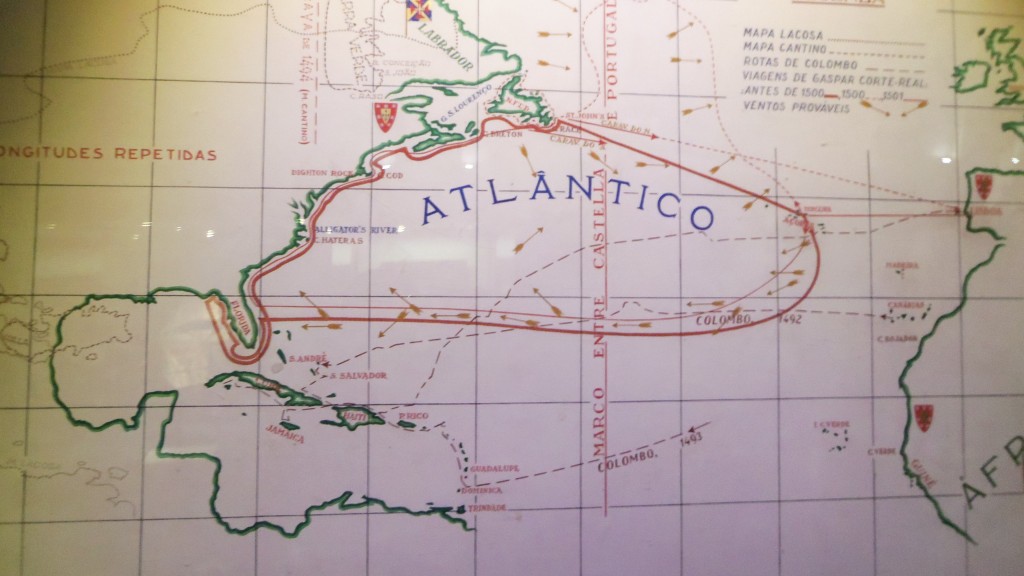

Portuguese Maritime Museum

I continued my pilgrimage at the Portuguese Maritime Museum. Tales of the sea, of men and civilization were oriented to the Portuguese citizen and a portrait of Christopher Columbus (who as described above was for at least a while Portuguese) was on display as was a chart depicting his Atlantic Crossings. In 1565, Italian chronicler Girolamo Benzoni wrote in his History of the New World that if Columbus had “lived in the time of the Greeks or of the Romans or any other liberal nation they would have erected a statue.”

Columbus sailed under the Castilian flag; Barcelona erected its 1888 column to mark that he reported to the Catholic Monarchs in that city.

In lieu of a statue, artists created paintings from descriptions of Columbus. None were done when he was alive. These paintings were very popular in the late 16th century. There were hundreds of different depictions of his image. The one at the Museum showed a man with blond and not reddish hair but I was please to see it. There is a world chart near the statue of Henry the Navigator which holds center stage at the museum.

The chart shows the paths of the great Portuguese explorers but did not include Columbus’ four Atlantic crossings. Columbus sailed for Spain but so did Ferdinand Magellan who proved Columbus’ was correct, that it was possible to sail around the world to the source of wealth for the Venetian monopoly. Note that Columbus had known of the Pacific Ocean from reports during his forth voyage to Panama and that Magellan died before completing Columbus’ quest to reach India.

If Spain is the head of Europe, Portugal, where land ends and sea begins, is the crown upon the head” sang Luis de Camoes, Portugal’s great national poet in 1572.