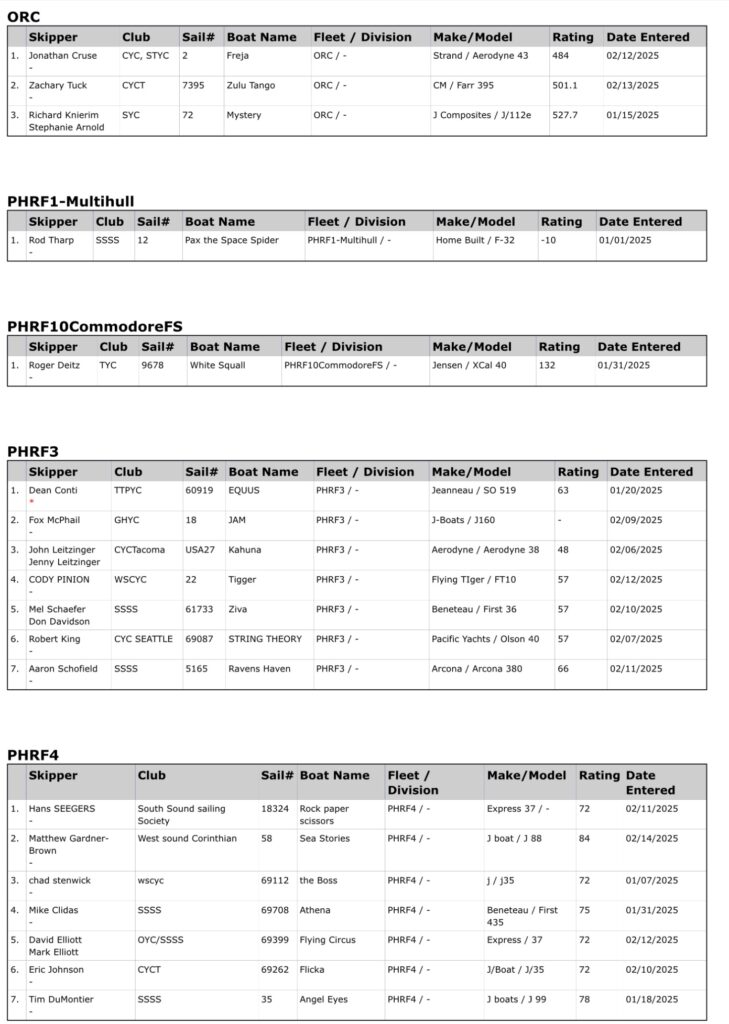

The 2025 Toliva Shoal Race sponsored by South Sound Sailing Society and Olympia Yacht Club was noteworthy because three sailboats raced in ORC class with one, a J112e making her first appearance on the 28 mile course. A description of the new boat precedes a discussion of ORC below. Conclusions regarding ORC and the accustomed PHRF rating are then made.

Overview of the J/112E

The J/112E is a high-performance cruiser-racer sailboat designed by Alan Johnstone and manufactured by J Composites, a licensed manufacturer for J/Boats, located in Les Sables d’Olonne, France.

Initially, production was focused in France, with plans to expand to the United States later12. The “E” in J/112E stands for “Elegance” and “Evolution”, reflecting its dual-purpose design as part of J/Boats’ performance cruising “E-Series” (e.g., J/97E, J/122E)68. Launched in 2015, it combines racing agility with cruising comfort, earning accolades like 2017 Sailing World Boat of the Year and SAIL Magazine Best Performance Boat over 30ft145.

Below is a detailed breakdown of its features, ratings, and competitive advantages.

- Design: 36.1 ft (11 m) monohull with a fractional sloop rig, carbon fiber mast, and resin-infused balsa/foam sandwich hull for lightweight durability134.

- Performance:

- Sail Area/Displacement Ratio: 22.09 (indicative of strong windward performance)3.

- Hull Speed: 7.55 knots, optimized for coastal and offshore sailing4.

- 2016 Chicago to Mackinac Race: Competed in heavy conditions, achieving speeds over 18 knots under spinnaker and securing a second-place finish in its section1.

- ORC Rating: Competitive under the ORC system, optimized for mixed conditions17.

- Accommodations: Two-cabin layout with a spacious saloon, galley, and CE Certification “A” for offshore use15.

Ratings and Speed Potential

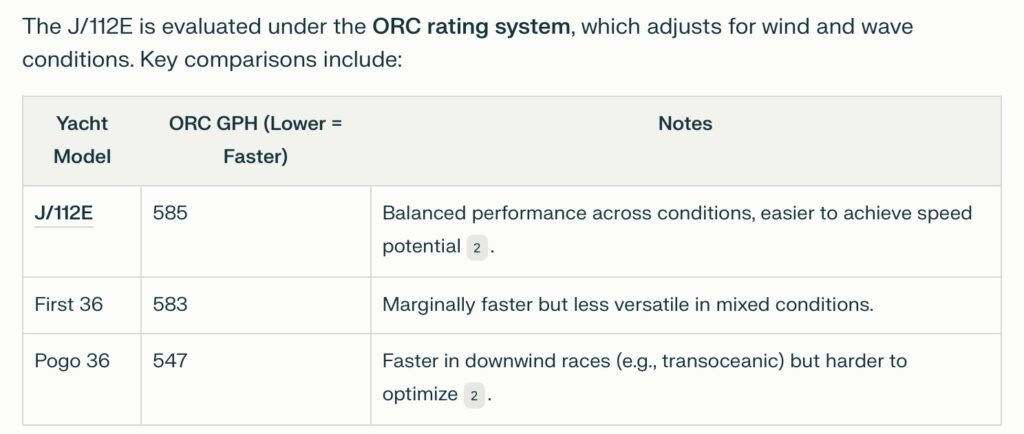

The J/112E is evaluated under the ORC rating system, which adjusts for wind and wave conditions. Key comparisons include:

- J/112E orc of 585 Balanced performance across conditions, easier to achieve speed potential2.

- First 36 orc of 583 Marginally faster but less versatile in mixed conditions.

- Pogo 36 orc of 547 – Faster in downwind races (e.g., transoceanic) but harder to optimize2.

The J/112E’s design prioritizes consistency, allowing it to perform well in both light winds and heavy seas without requiring extreme crew effort12.

Production Numbers

Exact production figures are not publicly disclosed, but the model has been in continuous production since 201535. Its popularity in regattas and cruising circuits suggests a robust global fleet.

Advantages Over Competing Racing Sailboats

The J/112E excels in versatility and user-friendliness:

- Dual-Purpose Design:

- Sail Handling:

- Build Quality:

- Award-Winning Ergonomics:

In summary, the J/112E stands out for its ability to transition seamlessly between racing and cruising, offering a rare blend of speed, comfort, and ease of handling124. While production numbers are undisclosed, its design and accolades cement its status as a top choice in the 36-foot performance sailing category. However there is No Water Ballast, Swing Keel or Rotating Mast.

- Water Ballast/Swing Keel: The J/112E uses a fixed fin keel with a lead bulb (6’11” draft standard, 5’9″ shoal option)147. It does not have water ballast or a swing keel.

- Rotating Mast: The standard rig includes a tapered aluminum mast (carbon mast optional)17. It does not feature a rotating mast, a carbon fiber mast is optional.

Pricing

- 2016 Base Price: Approximately $275,000 USD (adjusted for 2025 inflation, likely $325,000–$375,000+ depending on options)7.

- Key Options:

Performance Highlights

- Speed: Clocked at 18.2 knots downwind in the Chicago Mac Race1.

- Handling: Balanced helm, responsive rudder, and efficient sail plan (105% jib + retractable carbon sprit for asymmetric sails)37.

- Construction: SCRIMP resin-infused hull with balsa core and vinylester barrier coat for durability147 similar to other J boats.

For current pricing or race history details, contacting J/Boats dealers like Key Yachting or RCR Yachts is recommended28.

In summary, the J/112E has one rudder, no water ballast, a fixed keel, the mast does not rotate and the ORC rating system provides a single rating that is adjusted for different race conditions, not multiple ratings based on conditions as other ORC boats are.

Alan Johnstone designs

Alan Johnstone, the vice president and designer of J/Boats, has been instrumental in designing several models for the company. Some of the notable sailboats he has designed include:

- J/70: A 22.75-foot (6.9 m) day sailer and one-design racer.

- J/88: A 29-foot (8.8 m) one-design racer-cruiser.

- J/99: A 32.6-foot (9.9 m) offshore cruiser-racer.

- J/111: A 36.4-foot (11.1 m) one-design racer-cruiser.

- J/112E: A 36.1-foot (11 m) performance cruiser-racer.ORC Velocity Prediction Program (VPP) influence boat ratings

- J/121: A 40-foot (12.2 m) offshore racer.

- J/122E: A 40-foot (12.2 m) performance cruiser-racer.

- J/9: A 29.5-foot (9 m) day sailer introduced in 2021.

These designs reflect Alan Johnstone’s focus on creating boats that balance performance with comfort and practicality for both racing and cruising applications358.

The most popular J/Boat models include:

- J/24: With over 5,500 units built, it is the most successful J/Boat model and the world’s most popular one-design keelboat1.

- J/22: Over 1,650 units have been produced, making it another highly popular model among sailors1. The Seattle Yacht Club owns a fleet of J/22s

- J/70: Known as the world’s most popular sportboat, it is widely used for racing and day sailing68.

- J/35: A successful model with 330 units built, known for its performance in racing and cruising1.

These models are renowned for their performance, durability, and versatility in both racing and cruising applications. Not all J-boats use SCRIMP (Seemann Composite Resin Infusion Molding Process) method, but many models, particularly those produced after its adoption in the 1990s, utilize this advanced resin infusion technique.

The J/112E and J/122E are both part of J/Boats’ “E” series, designed for performance cruising. Here are the main differences:

Length and Layout

- J/112E: 36.1 feet (11 m) with a two-cabin layout, offering a more compact but versatile design for both racing and cruising12.

- J/122E: 40 feet (12.2 m) with a similar interior layout to the J/112E but with more space and options for customization37.

Performance and Handling

- J/112E: Known for its agility and upwind performance, it is well-suited for lighter crews and mixed conditions12.

- J/122E: Offers more stability and power due to its larger size, making it suitable for heavier weather and longer offshore passages47.

Keel Options

- J/112E: Standard draft is 6’11” with an optional 5’9″ shoal-draft keel3.

- J/122E: Offers three different keel options, providing flexibility for various sailing conditions7.

Interior and Features

- J/112E: Features a modern interior with ample natural light and a focus on comfort for short-handed sailing25.

- J/122E: Has an updated interior with more space, similar to the J/112E but with additional options for customization7.

Construction and Production

- Both models are built by J Composites in France, with the J/122E having an updated deck and interior compared to the original J/1227.

ORC System and Ratings

The term “ORC system” in sailing refers to the Offshore Racing Congress rating system. The ORC rating system is designed to provide a handicap for sailboats based on their performance under various conditions.

ORC ratings are calculated based on a boat’s design and performance characteristics, and they can vary slightly depending on the specific race conditions (e.g., wind, waves). However, a boat typically has a single ORC rating, which is adjusted for different race conditions using factors like wind speed and angle. This allows for fair competition across a range of conditions6.

ORC Measurements and Weighing

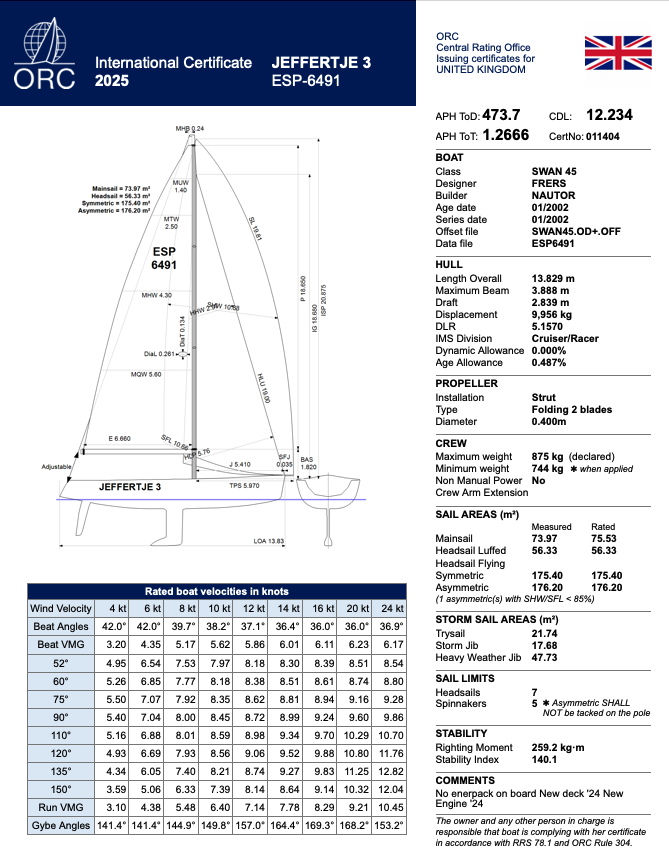

The ORC rating system uses detailed measurements of a boat’s characteristics, including:

Rig and Sails: Sail area, mast heights, and boom length.

Hull and Appendages: Measurements like freeboard, waterline length, and appendage dimensions.

Stability: Inclining tests to determine righting moment and stability.

Propeller Installation’s: Type and measurements.

The above conveys that ORC rating is complicated and ridged. This should be contrasted with the, familiar to South Sound sailors, Pacific Handicap Racing Fleet.

PHRF

The PHRF (Performance Handicap Racing Fleet) rating system has evolved significantly since its inception, adapting to technological advancements, regional needs, and shifts in sailing culture. Below is a summary of its key developments:

Origins and Early Development

- 1940s–1960s: Rooted in the West Coast’s “Arbitrary Fleet” system, PHRF emerged as an empirical alternative to complex measurement rules. By 1960, Southern California’s PHRF had over 350 members and was used in major races like the Newport Beach to Ensenada Race4.

- 1970s: PHRF expanded nationally, with US Sailing formalizing standards and regional fleets adopting the system. By 1973, the Pacific Handicap Racing Fleet rebranded as PHRF, becoming a nationwide phenomenon4.

Technological and Structural Advancements

- Computerization: In the 1970s, PHRF adopted early computer systems (e.g., GE’s CRT terminals) to manage growing membership and race data. By the 1990s, databases migrated to Microsoft Access, and websites (e.g., phrfsocal.org) provided public access to ratings4.

- Scoring Methods: Introduced Time-on-Time (ToT) and Time-on-Distance (ToD) scoring, with debates over fairness. ToT’s variable “B factor” (e.g., 480 for heavy air, 600 for light air) aimed to adjust for conditions but faced criticism for favoring higher-rated boats23.

- Dual and Triple Ratings: By 1995, Southern California implemented dual ratings (buoy vs. random leg courses) and later added an “Offwind Rating” (1999) for races with predominantly downwind legs4.

Adaptation to New Boat Designs

- 1980s–2000s: PHRF grappled with emerging designs like sport boats (asymmetrical spinnakers, retractable bowsprits) and high-tech features (water ballast, canting keels). Rules were revised to accommodate these innovations, such as regulating asymmetrical spinnaker sizes without automatic penalties4.

- Class Rule Refinements: Modified displacement definitions, eliminated bans on headfoils for cruising classes, and required owners to verify boat data accuracy4.

Regional vs. National Coordination

- Local Flexibility: Regions maintained autonomy, adjusting ratings ±12 seconds per mile based on local conditions. For example, a J/105 might have a PHRF of 93 in San Francisco vs. 117 in New England14.

- US Sailing’s Role: Standardized guidelines and a PHRF Handicap Book (compiling 5,000+ classes) aimed for consistency, but regional variability persisted13.

Modern Challenges and Innovations

- Perceived Flaws: Critics highlighted PHRF’s subjectivity, reliance on “Bristol condition” assumptions, and vulnerability to rating manipulation. Disputes over handicaps fueled perceptions of political bias12.

- Hybrid Systems: Regions like Southern California introduced PHRF Plus, blending empirical ratings with elements of measurement-based systems (e.g., ORC) for fairer competition4.

Legacy and Impact

PHRF’s evolution reflects sailing’s broader shifts—balancing accessibility with precision. While its empirical roots and regional adaptability sustained grassroots participation, controversies over fairness and complexity spurred innovations like computerized databases and multi-condition ratings. Today, PHRF remains a cornerstone of U.S. keelboat racing, even as newer systems like ORC gain traction among elite fleets.

PHRF is a performance-based system, relying less on precise measurements and more on observed performance:

- Basic Hull, Sail, and Rig Details: Owner-declared information.

- Observed Performance: Handicaps are assigned based on how boats perform in races, adjusted over time28.

PHRF is generally easier for designers to tweak because it is more subjective and based on observed performance rather than precise measurements. This allows for more flexibility in design modifications without significant re-measurement requirements.

The PHRF (Performance Handicap Racing Fleet) rating system has played a nuanced role in the decline of keelboat racing in the U.S., primarily through perceived unfairness, administrative challenges, and its inability to adapt to modern sailing trends. Here’s a breakdown of its impact:

1. Subjectivity and Perceived Unfairness

- Observed Performance vs. Measured Data: PHRF relies on historical race results and owner-reported data to assign handicaps, leading to inconsistencies. Sailors often dispute ratings, especially for modified or newer boats, creating a sense of arbitrariness.

- Regional Variability: PHRF ratings differ between regions (e.g., a J/105 might have a PHRF of 93 in San Francisco vs. 117 in New England), confusing sailors and undermining trust in the system.

2. Administrative Burden

- Volunteer Committees: Local PHRF committees often lack resources to audit boat modifications or update ratings promptly, resulting in outdated handicaps.

- Rating “Gaming”: Savvy sailors exploit loopholes (e.g., declaring smaller sails or omitting upgrades) to secure favorable ratings, alienating newcomers who lack insider knowledge.

3. Stifled Innovation

- Design Stagnation: PHRF discourages innovation because new boat designs or modifications risk unfavorable re-ratings. For example, a J/99 optimized for offshore racing might get penalized in PHRF despite its versatility.

- Arms Race Mentality: Owners invest in tweaks (e.g., rigging, sails) to “beat” their PHRF number rather than improve true performance, raising costs and excluding casual sailors.

4. Decline of Mid-Level Racing

- Fleet Fragmentation: PHRF struggles to balance diverse boats (e.g., 40-year-old IOR designs vs. modern foiling prototypes), leading to uncompetitive fleets. Many races now see only 3–5 boats per class, reducing excitement.

- Shift to Casual Events: Sailors increasingly prefer non-PHRF “beer can” races or distance events (e.g., Pacific Cup), where camaraderie outweighs competitive rigor.

5. Contrast with ORC

While the ORC system offers precise, measurement-based ratings, its complexity and cost ($1,500–$3,000 per certificate) make it inaccessible to many. PHRF’s simplicity initially appeals to casual racers, but its flaws—combined with sailing’s broader challenges (cost, aging demographics)—accelerate participation decline.

Why Does This Matter?

PHRF’s limitations exacerbate sailing’s reputation as a niche, insider sport. Young athletes, already deterred by cost and cultural irrelevance, see little incentive to engage with a system perceived as opaque or unfair. Meanwhile, alternatives like one-design racing (e.g., J/70s) or foiling classes (e.g., Waszps) attract youth by emphasizing simplicity and parity.

Pathways Forward

- Hybrid Systems: Regions like Southern California blend PHRF with ORC elements (e.g., SoCal PHRF Plus) for fairer scoring.

- One-Design Revival: Low-cost, strict-class boats (e.g., ILCA dinghies) sidestep rating debates entirely, fostering competitive equity.

In summary, while PHRF isn’t solely responsible for keelboat racing’s decline, its flaws amplify systemic issues. Modernizing handicaps—or shifting focus to ORC —could help reverse the trend.

Controversies Slowing ORC Adoption

Controversies include:

- Complexity: ORC’s detailed measurement requirements can be daunting for some users.

- Cost and Time: The process of obtaining an ORC rating can be more expensive and time-consuming compared to PHRF.

- Perception of Objectivity: While ORC is considered objective, some view its complexity as a barrier to adoption, preferring simpler systems like PHRF36.

Boat designers face several challenges when adapting to ORC ratings:

- Complexity of the System: ORC uses a sophisticated VPP (Velocity Prediction Program) that requires precise measurements and calculations, making it complex for designers to optimize their designs without extensive data and computational tools17.

- Stability and Inclining Tests: Designers must ensure their boats meet stability requirements through inclining tests, which can be time-consuming and costly18.

- Adaptation to Changing Rules: ORC regularly updates its rules and VPP models, requiring designers to stay current with these changes to maintain competitiveness12.

- Balancing Performance Across Conditions: ORC ratings aim to provide fair competition across various wind and sea conditions, which can be challenging for designers to optimize without compromising performance in specific conditions78.

- Cost and Time: The process of obtaining and maintaining an ORC rating can be more expensive and time-consuming compared to simpler systems like PHRF5.

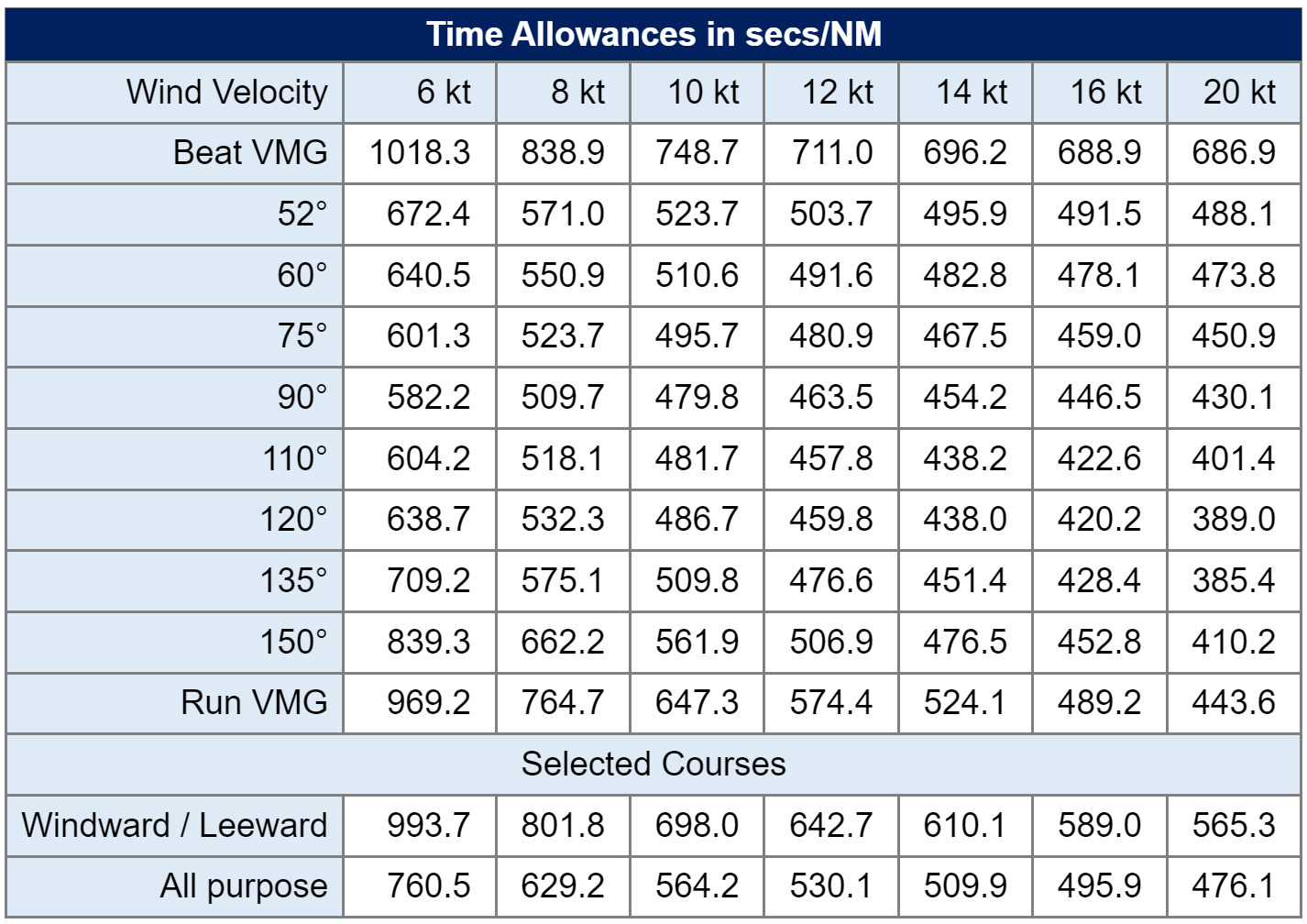

- ORC Velocity Prediction Program (VPP) influence boat ratings

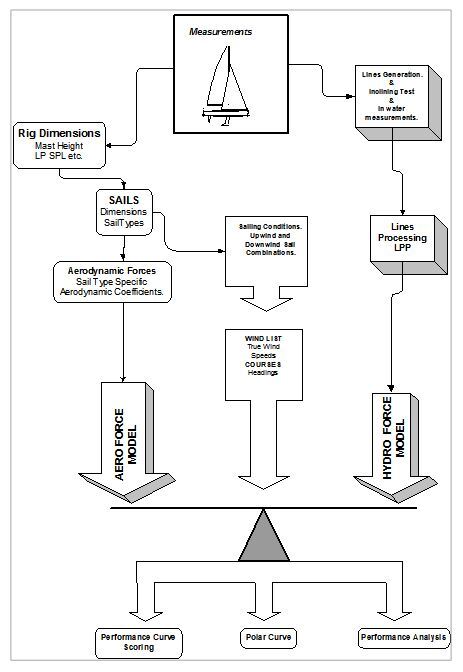

The ORC Velocity Prediction Program (VPP) significantly influences boat ratings by providing a sophisticated method to predict a boat’s performance under various conditions. Here’s how it impacts ratings:

- Performance Prediction: The VPP calculates a boat’s theoretical speeds at different wind strengths and angles, creating a comprehensive performance profile. This data is used to generate ratings that reflect a boat’s potential speed relative to others13.

- Equilibrium Equations: The VPP balances driving forces from sails with drag forces and heeling moments with righting moments, ensuring accurate predictions of a boat’s steady-state performance1.

- Rating Calculation: The VPP output is used to calculate handicap ratings, which are then applied to race scoring. This allows for fair competition by adjusting for differences in boat design and performance8.

- Design Optimization: The VPP provides designers with detailed insights into how design changes affect ratings, enabling them to optimize their designs for better performance under the ORC system5.

Developing a Velocity Prediction Program (VPP) for a racing sailboat currently involves significant costs, which are generally not covered by ORC rating fees.

Here’s a breakdown of expenses and ORC’s role:

Costs to Develop a VPP

- ORC Designer’s VPP Subscription:

- Annual Fee: €400–1,000/year (€400 for standard ORC VPP; €700–1,000 for superyacht ORCsy VPP)6.

- Features: Access to ORC’s proprietary software for simulating boat speeds, hydrostatics, and stability. Requires input of hull/rig measurements (e.g., DXT/OFF files).

- Naval Architect Fees:

- Basic Polars: $2,000–$5,000 (using existing data) [Avalon Offshore].

- Full VPP Development: $5,000–$10,000+ (incl. inclining tests, CFD analysis, and sail measurements) [Avalon Offshore, 1].

- Measurement Costs:

- ORC International certificates require full hull/rig measurements by certified engineers (~$1,500–$3,000)2.

ORC Rating Costs (Unrelated to VPP Development)

- ORC Certificate: $2.18–$13.15 per foot LOA (e.g., $8,700 for a 40-ft boat)2.

- Speed Guide (Polars): $35 (subsidized rate via ORC)2.

- Trials: $50–$100 per modification (e.g., sail changes, crew weight)2.

Key Takeaways

- ORC provides tools (VPP software) but does not cover the cost of developing custom VPPs.

- Designers/owners must pay for:

- ORC software subscriptions.

- Naval architect services.

- Measurement and certification.

- Pre-existing VPP data (e.g., Avalon Offshore’s 470+ models) can reduce costs for common designs7.

Why This Matters

While ORC streamlines rating calculations, developing a competitive VPP for ORC remains costly though it need not be. Cruising Sailors know that PredictWind AI Polars are determined real-time from a boat’s instruments via the DataHub, incorporating GPS speed, apparent wind speed, and wave conditions12. These polars are used for route planning. Of course the operator’s sailing style may not be competitive for racing but someone sailing the same model boat may have a competitive sailing style. That polar should be acceptable for the purpose of ORC.

Hence, paying for custom VPP development for boat models currently racing PHRF so they can race ORC seems premature. The fairness afforded ORC racers through VPP can be obtained by waiting for PHRF plus VPP or for ORC to incorporate PredictWind polars so that it is less costly.

ORC (Offshore Racing Congress) rating system is gaining popularity and might continue to do so, especially among younger athletes and those involved in high-performance sailing. The ORC system is known for its sophisticated Velocity Prediction Program (VPP) which provides a fair and accurate rating for a wide variety of new model boats, making it attractive for competitive racing.

On the other hand, the PHRF (Performance Handicap Racing Fleet) system is simpler and more cost-effective, making it popular among grassroots and casual racers. However, it has faced some challenges and controversies, such as its perceived lack of accuracy and governance issues which may be responsible for the decline of interest among young athletes in the sailing sport,

In conclusion, while ORC might see increased adoption, especially among younger and competitive sailors, PHRF is likely to remain relevant for local and casual racing due to its simplicity and lower cost. There is also the opportunity of using America’s Cup technology (specifically its sponsor’s PredictWind software) to make PHRF fair through AI.

Both systems will probably continue to coexist, catering to different segments of the sailing community with those newer to the sport favoring ORC.