Another charming Whidbey locale, Coupeville’s recently refurbished pier features the new Native women-run coffee shop, Beaver Tales Coffee. It’s also close to Ebey’s Landing, one of the most breathtaking hikes on the island, with jaw-dropping views of the sound and distant Olympic Mountains.

13 small towns near Seattle that are absolutely worth a visit

A Maritime Adventure Near Coupeville: Where History, Naval Heritage, and Natural Wonder Converge

For families seeking an enriching destination that seamlessly blends maritime history, natural beauty, and cultural significance, the area surrounding Coupeville on Whidbey Island, Washington presents an extraordinary opportunity. This unique region offers compelling experiences for historians, naval architects, wildlife enthusiasts, hikers, sailors, those interested in Indigenous culture, wooden boat aficionados, and photographers alike.

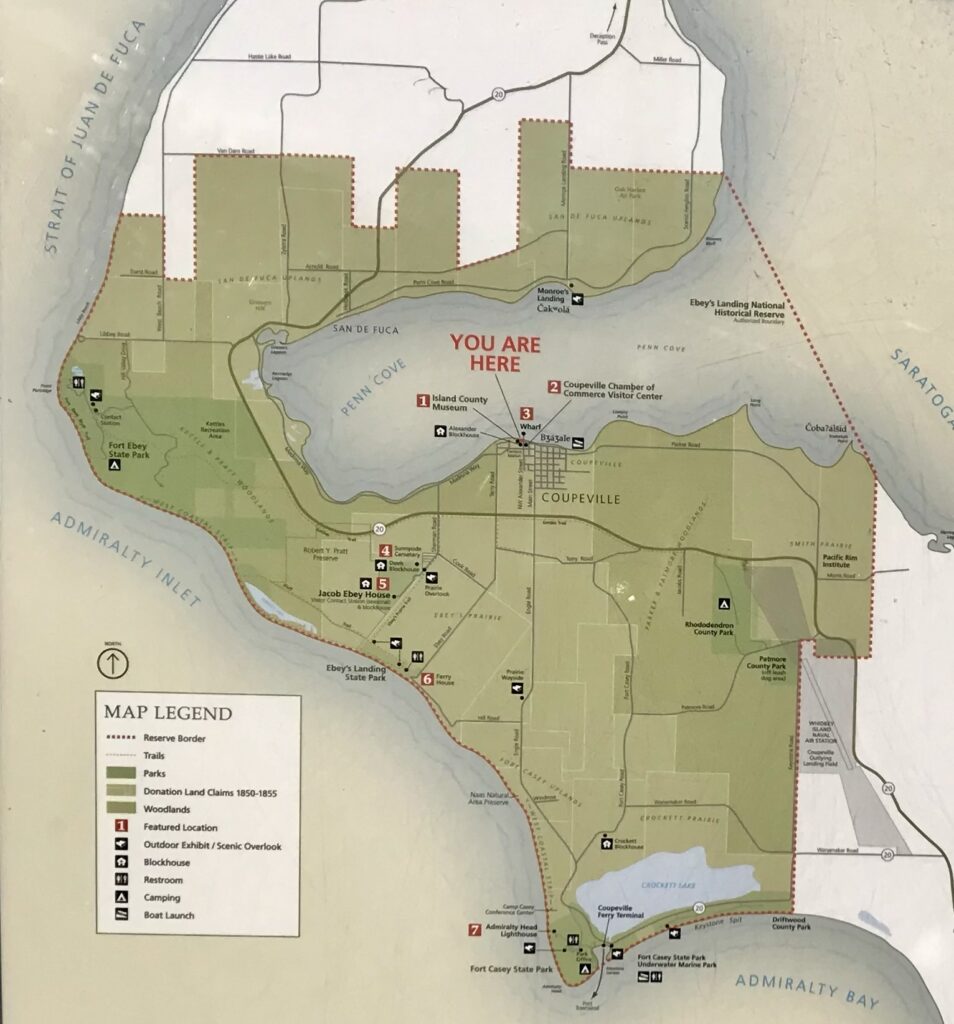

Ebey’s Landing National Historic Reserve: America’s First National Historic Reserve

Ebey’s Landing National Historic Reserve stands as the crown jewel of the region, established in 1978 as the nation’s first national historical reserve. This remarkable 17,400-acre area preserves an unbroken historical record of exploration and settlement in Puget Sound, representing a unique preservation model based on partnerships between government and citizens. The Reserve encompasses not just historical sites, but an entire living landscape where farms, historic buildings, and archaeological sites tell the story of human habitation spanning over 10,000 years.

For historians, the Reserve offers an extraordinary window into Pacific Northwest settlement patterns. The area was first inhabited by the Lower Skagit People, who established permanent villages including bah-TSAHD-ah-lee (snake place), the largest being located at present-day Coupeville1.

The maiden of Deception Pass

Ko-Kwal-alwoot and other maidens were gathering sea food on the beach one day, when one of the shellfish slipped from her grasp and fell into deeper water. She reached for it, and it slipped from her hand again and again, and she kept following it until she was in deep water, well over her waist. Suddenly she realized that what seemed to be a hand had grasped hers and was holding her there. Terrified, she attempted to free herself, but a voice told her not to struggle or be afraid, that she was very lovely, and he was merely holding her there so that he could look upon her beauty. Soon her hand was released, and she returned to her people.

After a number of such meetings, during which the spirit held her hand longer and longer each time, and spoke soothingly to her, telling her of the many beautiful things which were in the sea, there came a day when a young man emerged from the water, and accompanied her to her father’s house, to ask for her hand in marriage. The people of the village knew not from whence he came, or who he might be, but they noticed that in his presence they were chilled, as though icy winds were blowing. At first when he asked for Ko-Kwalalwoot’s hand, her father was indignant and said “No, my daughter cannot go into the sea with you-she would die.” “On the contrary,” said the young man, “she will not die; we will give her eternal life, and we will be very good to her, for I love her dearly.” Then he warned the father that if he could not have Ko-Kwal-alwoot for his bride, all the sea food would be taken from them, and they would be very hungry, but the father still would not agree. As time went on, there was a great scarcity of food of all kinds, and even the streams started to dry up, so that they could have no water to drink.

When she could stand it no longer, Ko-Kwal-alwoot went out into the water, and called the young man, begging him to give her people food.

But he replied, “Tell your father that only when you are my bride, will the waters teem with fish, and your people may again live in plenty.” At last her father, realizing that his people were starving, reluctantly agreed to give up his daughter so that the many members of his tribe might live. He made one stipulation, however, and that was that she was to return to her people for a visit once a year, so that they could see if she was being cared for and was happy. This was agreed upon, and Ko-Kwal-alwoot, wrapping her garments about her, walked into the water, farther and farther until she was out of sight, and only her hair could be seen floating in the current.

True to the agreement, there was food in plenty, and the tribe prospered. And Ko-Kwal-alwoot returned to her people once each year, and before her coming there was always more food than ever before. Still each time she came, her people noticed more and more of a change in her. Barnacles grew upon her hands, up to her arms, and the last time she came they had started to grow upon the side of her face which had been so beautiful, and her people felt the chill winds wherever she walked, and they noticed that she seemed to be unhappy out of the sea. On her last visit they told her she did not need to return to them again, unless it was her wish to do so. Since that time she has been their guiding spirit, and through her efforts there has always been plenty of shell fish and food of all kinds in that vicinity, and the spring water has always been pure and sweet. The Samish Tribe believes that as the currents flow back and forth through Deception Pass, her hair may be seen drifting gently with the tide, and that she is always there to look out for the welfare of her people.

as told by Charlie Edwards to Martin Sampson, 1938

The protected harbor at Penn Cove provided abundant salmon, clams, mussels, flounder, sole, and cockles, making it a political and cultural center for Coast Salish peoples12.

The hiking opportunities within the Reserve are exceptional, featuring the Bluff Loop Trail that provides spectacular views of the Puget Sound and Olympic Mountains.

Families with RVs can access the Reserve’s numerous trail systems, though caution is advised on the Bluff Loop due to erosion. The Robert Y. Pratt Preserve at Ebey’s Landing offers 19th-century settler sites and scenic water views along well-maintained trails suitable for families.

Fort Casey was activated to provide strategic defense of Admiralty Inlet and the Puget Sound. The fort was a catalyst in bringing more people to central Whidbey Island.

Fort Casey Historical State Park: Naval Architecture and Military Engineering

Fort Casey Historical State Park represents a fascinating convergence of military history and naval architecture, built in 1890 as part of the “Triangle of Fire” defense system3. Naval architects and history enthusiasts will find the fort’s engineering remarkable—designed to protect Puget Sound’s entrance with 10-inch disappearing guns that could launch shells over 10 miles3. The fort housed 400 troops at its peak and featured innovative military architecture including underground tunnels, bunkers, and strategic gun emplacements3.

The park offers exceptional RV camping facilities with 35 campsites accommodating RVs up to 40 feet, including 14 sites with water and electric hookups4. Four beachfront pull-through sites provide direct access to 10,000 feet of saltwater shoreline4. The park features two watercraft launches, making it ideal for families arriving by boat4.

Admiralty Head Lighthouse, located within Fort Casey, showcases the architectural brilliance of Carl Leick, one of America’s premier lighthouse architects5. Built in 1903, this Spanish-style lighthouse features stucco walls, ironwork, and arches that create stunning photographic opportunities5.

The lighthouse operates seasonally with volunteer docents providing educational tours and historical interpretation6.

The Coupeville Wharf and Penn Cove: Maritime Heritage Hub

In response to the growth in population from the establishment of Fort Casey, local merchants and farmers built a 500-foot dock extending into Penn Cove at the foot of NW Alexander Street in 1905. The Coupeville Wharf, as it was called, included an L-shaped building with a waiting room and restroom that served as a passenger ferry terminal and became an important community center.

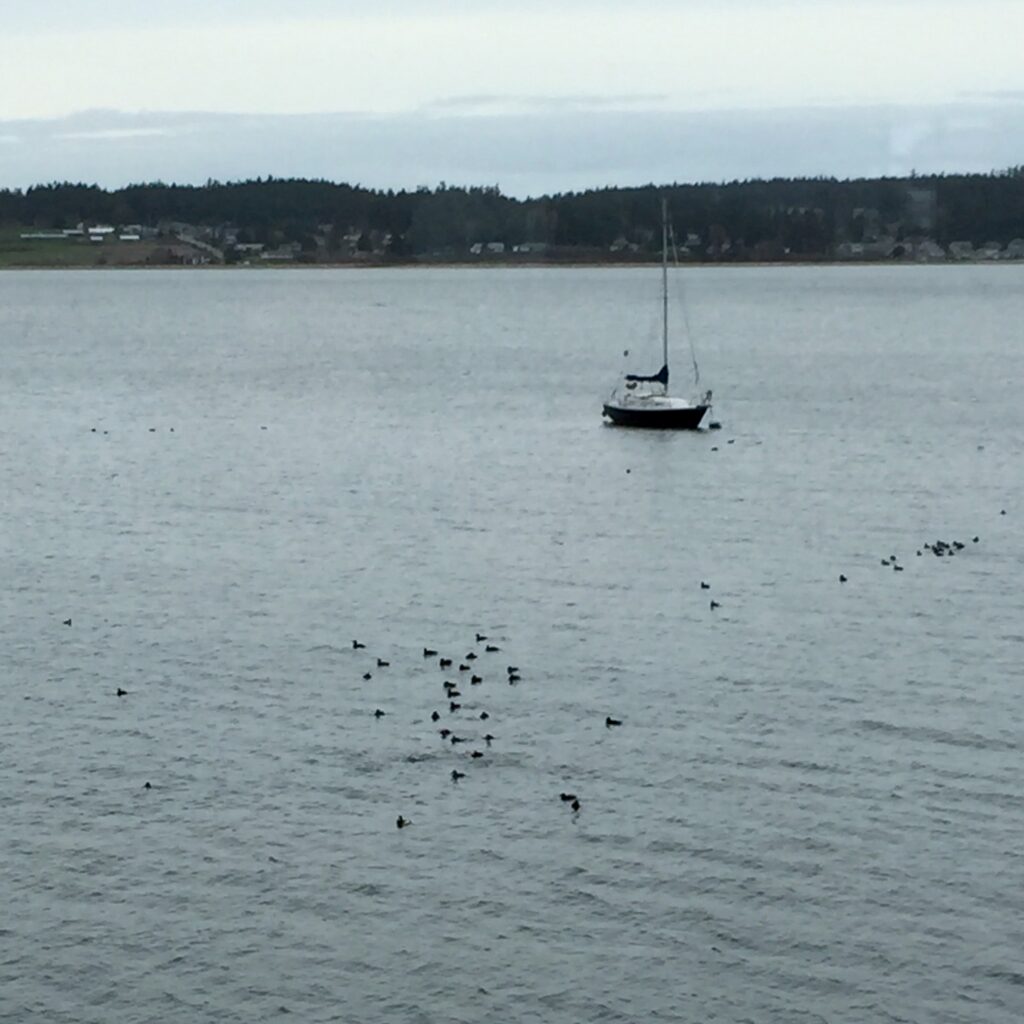

Today the Coupeville Wharf serves as both a functional marina and a living museum of maritime heritage. The iconic red building creates dramatic photographic compositions, particularly during golden hour, while the wharf provides excellent wildlife viewing opportunities where visitors can observe seals, sea birds, and occasional orcas.

Penn Cove’s significance extends beyond its scenic beauty—it’s home to Penn Cove Shellfish, one of the Pacific Northwest’s premier mussel farming operations7.

The nutrient-rich waters, fed by the Skagit River and enhanced by the Olympic Mountains’ rain shadow effect, create ideal conditions for mussel cultivation8.

Families can observe the harvest process from shore or participate in seasonal boat tours during the Penn Cove Musselfest, which offers 45-minute educational tours of the mussel farm9.

For naval architects and maritime enthusiasts, Penn Cove represents a natural harbor that has sheltered vessels for millennia. The cove’s protected waters and strategic location made it a gathering place for Coast Salish peoples and later attracted European and American maritime interests1.

Schooner SUVA: Living Maritime Heritage

The Schooner SUVA offers an authentic tall ship experience that brings maritime history to life. This historic wooden sailing vessel, operated by the Whidbey Island Maritime Heritage Foundation, provides day-sails and private charters with US Coast Guard certified captains and trained volunteer crew. The SUVA’s 2025 sailing schedule includes Friday sunset sails and weekend afternoon voyages, with adult tickets at $75 and youth tickets at $5010.

For wooden boat enthusiasts, the SUVA represents traditional maritime craftsmanship and sailing techniques. The vessel provides hands-on experience with traditional rigging, sail handling, and navigation methods that connect visitors to centuries of maritime tradition.

The History of Schooner Suva

The Birth of Schooner Suva: A Century-Old Maritime Legacy

The schooner Suva represents one of the Pacific Northwest’s most significant maritime treasures, with a history spanning exactly one hundred years. Frank Pratt Jr., a Massachusetts lawyer who moved to Whidbey Island in 1908, commissioned the vessel in 192412. Pratt had a clear vision for what he wanted—not a racing yacht, but “an auxiliary motor yacht that would be comfortable for business and family use”1.

To realize this vision, Pratt enlisted Ted Geary, one of Seattle’s most renowned naval architects13. Leslie “Ted” E. Geary (1885-1960) was already establishing himself as a master designer who would eventually create some of the most celebrated vessels on the West Coast45. The collaboration between Pratt and Geary would produce what has been described as a “pioneering pilot house schooner” that embodied the elegance of the Gatsby era62.

Construction and Design: Old Growth Craftsmanship

Suva was built in 1925 at Quan Lee Shipyard in Hong Kong during British occupation, constructed entirely from old growth Burmese teak—500-year-old wood that represented the finest shipbuilding material available16. The choice to build in Hong Kong was strategic, as the British colony offered access to exceptional craftsmanship and premium materials at reasonable cost.

After construction, the vessel was barged across the Pacific Ocean to Victoria, British Columbia, where her Sitka spruce masts were installed and rigging completed12. The 68-foot schooner was originally designed as a gaff-rigged vessel, featuring the four-sided sails characteristic of 1920s sailing craft1. Her dimensions were impressive for a private yacht: 65 feet overall length, 58 feet on deck3.

Ted Geary: The Naval Architect Behind Suva

Ted Geary’s involvement in Suva’s design represents just one chapter in an extraordinary career that helped define Pacific Northwest maritime architecture. Born in 1885 in Atchison, Kansas, Geary moved to Seattle with his parents in 18924.His attraction to water-related activities manifested early—at age 14, he designed and built his first racing sloop, the 24-foot Empress4.

Geary’s talent attracted the attention of prominent Seattle businessmen who financed his education at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he studied naval architecture45. Upon graduation in 1910, Geary returned to Seattle and established a practice that would produce hundreds of vessels, from commercial craft to luxury yachts5. His designs included Sir Tom, an “R” class boat that dominated West Coast racing for three decades, and the first diesel-powered tugboat in the United States, Chickamauga45.

Suva represented Geary’s expertise in designing comfortable cruising vessels rather than pure racing machines. The boat featured innovative elements including a pilot house configuration that provided excellent visibility and protection, while maintaining the classic lines that made Geary’s designs instantly recognizable7.

Early Years in Penn Cove: 1925-1940

From her maiden voyage in 1925, Suva was anchored in Penn Cove at Coupeville, where she remained for the first fifteen years of her existence38. Frank Pratt used the vessel for both business and family purposes, entertaining clients and enjoying family outings on the protected waters of Penn Cove and the broader Puget Sound.

The name “Suva” reflects Pratt’s personal connections—according to maritime heritage foundation legend, Frank Pratt’s uncle was a civil engineer who helped lay out the city of Suva, the capital of Fiji. Frank had visited his uncle as a young man and admired the city, which even has a street named Pratt Street3.

Evolution Through Multiple Owners

When Frank Pratt’s health began to deteriorate (he died in 1939), he was concerned about Suva’s future. Dietrich Schmitz, who served as Pratt’s financial adviser, purchased the boat for one dollar in 1940—Pratt wanted to give it as a gift, but Schmitz insisted on paying8. This transaction began a 45-year period during which Suva remained in the Schmitz family.

In 1960, Suva underwent a major refit that transformed her from a gaff-rigged schooner to a staysail schooner3.The original Lawson-Scott gasoline engine was replaced with a more reliable 140-horsepower Detroit 453 diesel engine—a two-cycle, four-cylinder powerplant that would serve the vessel for decades3.

The Schmitz family’s stewardship ended in 1985, when the boat was sold to Bill Brandt of Olympia, who owned her for approximately 25 years3. Suva then moved to Port Townsend under the ownership of Scott Flickinger, followed by Lloyd Baldwin, who purchased the vessel in 20093.

Rescue and Restoration: Return to Penn Cove

In 2015, Mark Saia, founding member of the Coupeville Maritime History Foundation (later renamed the Whidbey Island Maritime Heritage Foundation), discovered Suva listed on Craigslist, anchored in Port Townsend62. Recognizing the vessel’s historical significance and educational potential, Saia orchestrated her purchase for $110,000 through community donations62.

The acquisition represented more than just buying a boat—it was bringing home a piece of Whidbey Island’s maritime heritage. The foundation, which became Suva’s sixth owner, committed to operating the vessel with an all-volunteer crew and maintaining her historical integrity while making her accessible to the public3.

The Half Model at Seattle Yacht Club: Maritime Tradition

The presence of a half model of Suva at the Seattle Yacht Club reflects a maritime tradition that dates back centuries. Half models were originally created by shipyards as design tools and later became symbols of maritime achievement displayed in yacht clubs worldwide910. These three-dimensional representations, typically showing half of a vessel’s hull bisected vertically down the symmetrical plane, served both practical and ceremonial purposes11.

Many yacht clubs established cultures where members displayed half models of their prized yachts on clubhouse walls, creating opportunities for recognition and status within the maritime community910. The New York Yacht Club’s famous “Model Room” represents the most celebrated collection of such displays9.

The Seattle Yacht Club, founded in 1892 and listed on the National Register of Historical Places in 201012, has long maintained connections to significant Pacific Northwest vessels. The club’s relationship with Ted Geary was particularly strong—Geary designed several boats for club members and competitions, including the Spirit, a 42-foot racing sloop that successfully challenged for the Dunsmir Cup in 1907413.

The half model of Suva at Seattle Yacht Club likely represents recognition of both the vessel’s historical significance and Ted Geary’s contributions to Pacific Northwest naval architecture. As one of Geary’s notable designs and a boat with nearly a century of local maritime history, Suva merits commemoration in the region’s premier yacht club.

Contemporary Legacy: Living Maritime Heritage

Today, Suva continues her centennial celebration as an active sailing vessel operated by the Whidbey Island Maritime Heritage Foundation14. The foundation offers public sailing experiences that connect visitors to maritime history while maintaining the vessel’s authentic character. Despite modifications over the decades, Suva has retained her Gatsby-era elegance, with original Burmese teak construction, brass fittings, and wooden interior that Captain Brian Vick describes as “a gorgeous boat”62.

The schooner’s story represents the broader narrative of Pacific Northwest maritime development—from the vision of early settlers like Frank Pratt, through the genius of designers like Ted Geary, to contemporary efforts to preserve and share maritime heritage. Suva’s half model at the Seattle Yacht Club serves as a permanent tribute to this century-long journey, honoring both the vessel’s individual significance and her place in the region’s maritime legacy910.

As maritime historians note, the tradition of displaying half models in yacht clubs creates lasting connections between past and present, ensuring that significant vessels and their stories remain visible to future generations of maritime enthusiasts911. In Suva’s case, this display represents not just a boat, but a century of Pacific Northwest maritime heritage, craftsmanship, and community stewardship.

Wildlife and Marine Ecosystem

The Penn Cove and surrounding waters support an extraordinarily diverse marine ecosystem. Recent wildlife observations include the historic return of Southern Resident killer whales to Penn Cove for the first time in 53 years—a remarkable event given the traumatic captures that occurred there in 1970-197111.

The whales’ return coincides with exceptional chum salmon runs, with 2024 seeing nearly 900,000 chum returning to central and south Puget Sound streams11.

The area supports over 230 bird species, making it exceptional for wildlife photography and birding12. Penn Cove specifically attracts kingfishers, Great Blue Herons, loons, goldeneyes, bufflehead, scaup, and pigeon guillemots12.

The waters contain over 3,000 species of invertebrates, including geoduck clams, oysters, octopus, sea urchins, Dungeness crab, and sea stars12.

Harbor seals are commonly observed from the wharf, providing excellent photography opportunities and educational experiences for families. The marine sanctuary status of much of the surrounding waters helps protect these diverse ecosystems.

Shellfish Harvesting and Marine Resources

The region offers exceptional opportunities for recreational shellfish harvesting, managed by Island County’s Shellfish Resources program in coordination with the Washington State Department of Health13. The program ensures safe harvesting through regular water quality monitoring and marine biotoxin testing13.

Before harvesting, families must verify that both the Department of Health status and Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife seasons are open14.

Popular shellfish species include Manila and native littleneck clams, butter clams, horse clams, cockles, and Eastern softshell clams14.

The area’s beaches provide excellent educational opportunities for families to learn about marine ecosystems while potentially harvesting their own dinner14.

The first Native American Canoe Races launched with three, 11-man canoes. Over time, up to 22 tribes competed. The annual celebration of Native American culture brought Native Americans together from around the region. World War Il paused the festival, but it was re-started in the 1990s and continues today as the Penn Cove Water Festival. Island County Historical Society Museum

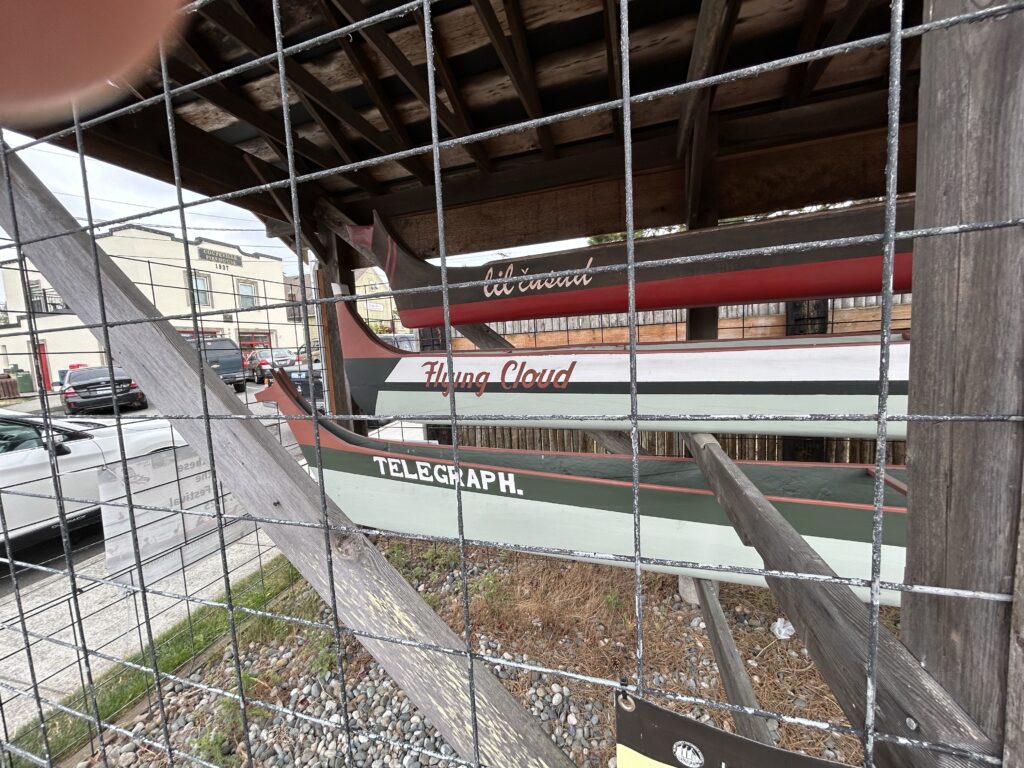

Canoes shown above and discussed below.

The FLYING CLOUD – A Racing Canoe

This canoe was carved by Howard and Ronald Tom of the Upper Skagit Tribe when they were teenagers living near the Skagit River around 1930. It won numerous championships in the canoe races every year during that time. In the early 1940s, Harry Race, a prominent Alaska pharmacist, purchased the Flying Cloud and had it shipped there when the Indian Water Festival halted due to World War II. The Ketchikan natives for whom he bought the canoe, however, would not race it. It sat in storage for a decade until Native Americans from Bow took possession of it for use in the Lummi Regatta. Many years later, after being retired from racing, it was donated to the Island County Historical Society Museum for display.

The TILIKUM – A Tip Over Canoe

This two man canoe was made by Aleck Kettle in 1933. During the canoe races this canoe was paddled a short distance along the course, and When a competitor approached, paddlers stopped their canoes and stood up while holding a long pole with a padded end. The goal was to push your competitor out of the canoe and tip it over. After a tip-over, the paddlers then had to right the canoe, empty it of water, climb back in and continue the race.

The L’IL CUSAD – a Tulalip canoe

This canoe, carved approximately 20 years ago, is a replica of a much larger canoe from the Tulalip Tribe. “Cusad” is a Lushootseed word for “star”.

Indigenous Cultural Heritage

The region’s Indigenous heritage runs deep, with Coast Salish peoples including the Lower Skagit, Snohomish, and Kikialus tribes having inhabited these lands since time immemorial15. The Snohomish established three permanent villages on South Whidbey Island, including dəgʷasx̌ (meaning “in the basket”) at Cultus Bay, which featured six or seven longhouses, two cemeteries, and a potlatch house15.

Canoes

The TELEGRAPH – A Racing Canoe

This canoe was carved out of cedar in 1905 by Charles and Dick Edwards and Andrew Joe of the Swinomish Tribe. The 51-foot Telegraph was the winner of the International Canoe Races held in Coupeville every year between 1929 – 1941. Manned by 11 men, including the original carvers, it averaged 60 strokes per minute over the three mile course – total race time was 22 minutes, 30 seconds.

The ELSON – One Man Hurdle Canoe

This canoe was made by Aleck Kettle, last of the Lower Skagit People to live on Whidbey Island, for his youngest grandson, Elson. Entered in the 1934 Coupeville canoe races, the canoe was paddled up to a greased log anchored along the race course. Speed and timing had to be perfect because as the bow of the canoe reached the log, the paddler threw his weight backwards, lifting his canoe bow high enough to top the log. Then with a powerful stroke of the paddle, the paddler threw his weight forward to slide over the log. The goal was to keep the canoe upright and continue on to the finish line.

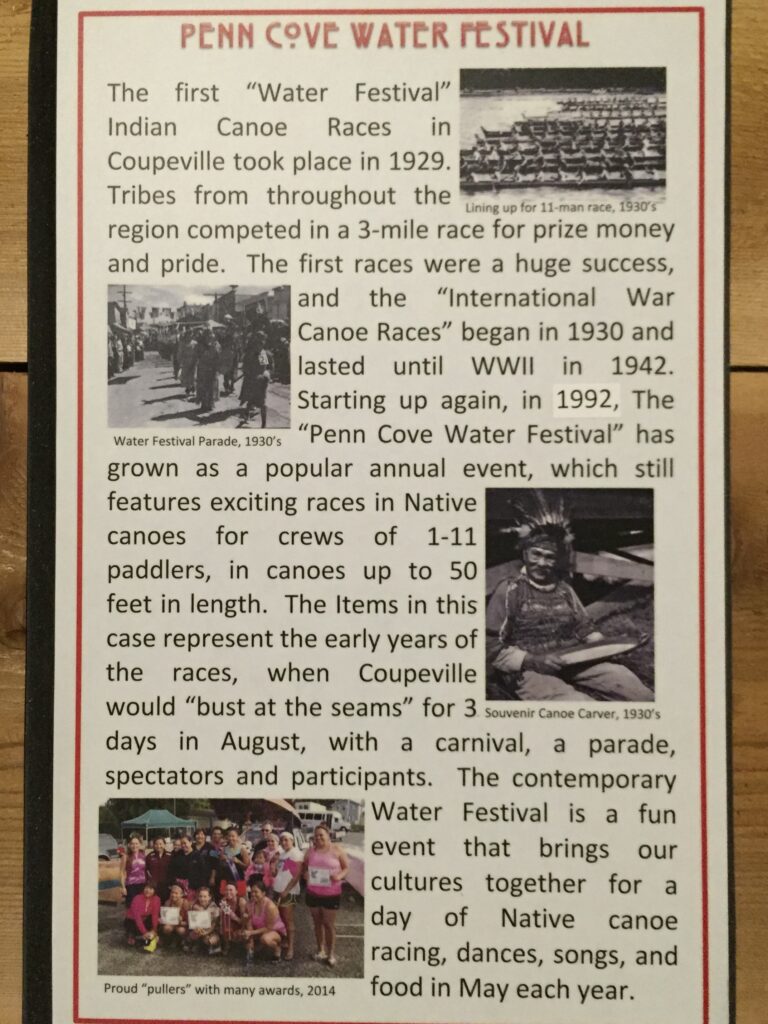

PENN COVE WATER FESTIVAL

The first “Water Festival” Indian Canoe Races in Coupeville took place in 1929. Tribes from throughout the region competed in a 3-mile race for prize money and pride. The first races were a huge success, and the “International War Canoe Races” began in 1930 and lasted until WWll in 1942.

Starting up again, in 1992, The Water Festival Parade, “Penn Cove Water Festival” has grown as a popular annual event, which still features exciting races in Native canoes for crews of 1-11 paddlers, in canoes up to 50 feet in length.

The Water Festival is a fun event that brings our cultures together for a day of Native canoe racing, dances, songs, and food in May each year.

The Island County Historical Museum in Coupeville provides comprehensive exhibits on Native American life, displaying artifacts and interpretive materials that honor the region’s first inhabitants16. An entire floor is devoted to Coast Salish culture, offering visitors deep insights into traditional lifeways, seasonal rounds, and cultural practices16.

MOHAI, Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection, P123853

For those interested in Indigenous history, several historical blockhouses remain from the 1850s conflicts, including the Alexander Blockhouse moved to Coupeville in the 1930s17.

These structures represent the complex period of cultural contact and conflict during territorial settlement17.

Naval and Aviation Heritage

The Pacific Northwest Naval Air Museum in nearby Oak Harbor provides extensive exhibits on naval aviation history, featuring a restored PBY-5A Catalina seaplane—one of the first aircraft to fly from NAS Whidbey Island during World War II18. The museum offers interactive experiences including flight simulators, a PBY nose gun turret, and hands-on exhibits covering naval aviation from WWII through current operations19.

Naval architects will appreciate the museum’s detailed coverage of aircraft design evolution, from the versatile PBY Catalina to modern EA-18G Growlers18. The museum’s 11 display areas span multiple conflicts and showcase the technological advancement of naval aviation19.

Photography and Scenic Beauty

The region offers exceptional photographic opportunities across multiple disciplines. Deception Pass Bridge provides iconic Pacific Northwest imagery, best captured from viewpoints north of the bridge20.

Deception Pass bridge opens to allow – for the first time ever – automobile access to and from Whidbey Island. The bridge received rave reviews for its engineering and elegant architecture that rivals the scenic setting.

One year after the opening of the Deception Pass bridge, passenger service from the Coupeville Wharf was suspended as automobiles became the preferred mode of transportation. The end of an era.

The Coupeville Wharf’s red building creates dramatic compositions, particularly during morning golden hour20.

Ebey’s Reserve Scenic Overlook offers afternoon and sunset photography opportunities with expansive views of farmland, water, and distant mountains20.

The historic blockhouses scattered throughout the landscape provide unique foreground elements for landscape photography20.

English Boom Historic Park on Camano Island presents sunrise photography opportunities in a setting where human history meets natural reclamation20. The contrast between historical industrial remnants and returning natural systems creates compelling photographic narratives.

Practical Considerations for Families

For families traveling with boats, the region offers multiple launch facilities including Captain Coupe Park with floating docks and trailer parking21, Keystone Spit Boat Ramp at Fort Casey22, and Cornet Bay Marina at Deception Pass State Park21. The new Keystone Boat Launch, rebuilt in 2023 after storm damage, provides modern facilities with new floats and breakwater protection22.

RV camping options include Fort Casey State Park with 35 sites including hookups4, Fort Ebey State Park with 50 sites23, and several private facilities. The Rhododendron Campground near Coupeville offers forest views and trail connections23.

The region’s compact geography allows families to experience multiple interests within a small area. From the maritime heritage of the wharf to the military history of the forts, from Indigenous cultural sites to world-class shellfish farming, from tall ship sailing to wildlife viewing, the Coupeville area presents an integrated experience where each element enriches understanding of the others.

This remarkable destination demonstrates how natural beauty, cultural heritage, and maritime tradition can be preserved and shared, creating experiences that educate, inspire, and connect visitors to the deeper currents of Pacific Northwest history and ecologygy.