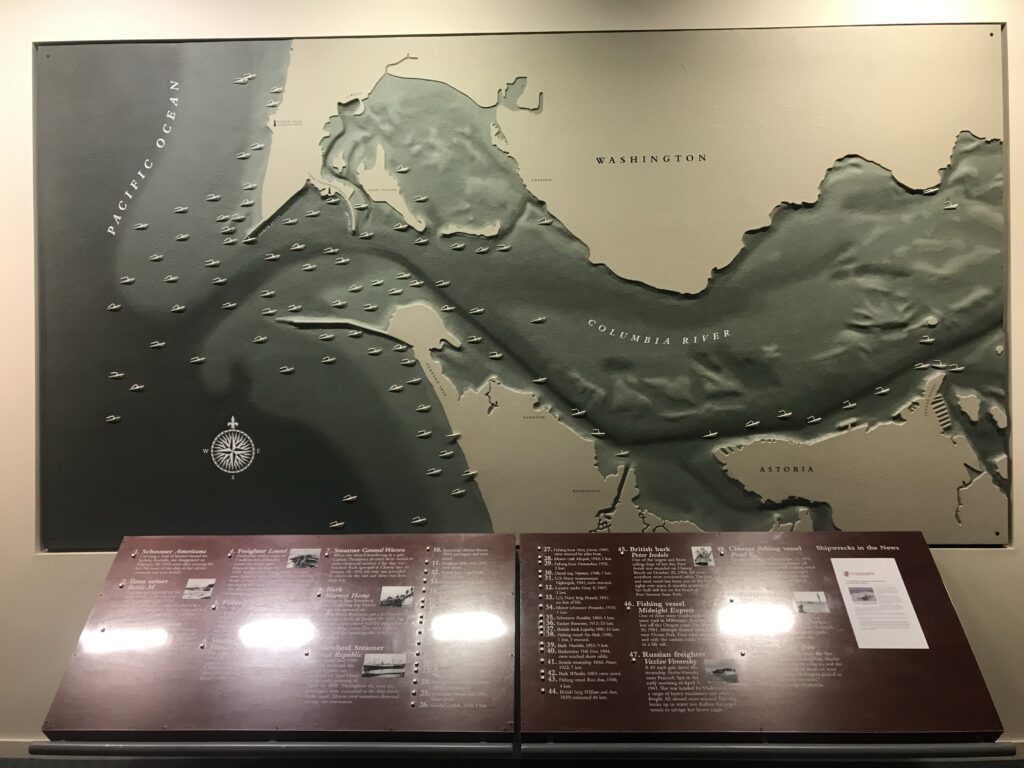

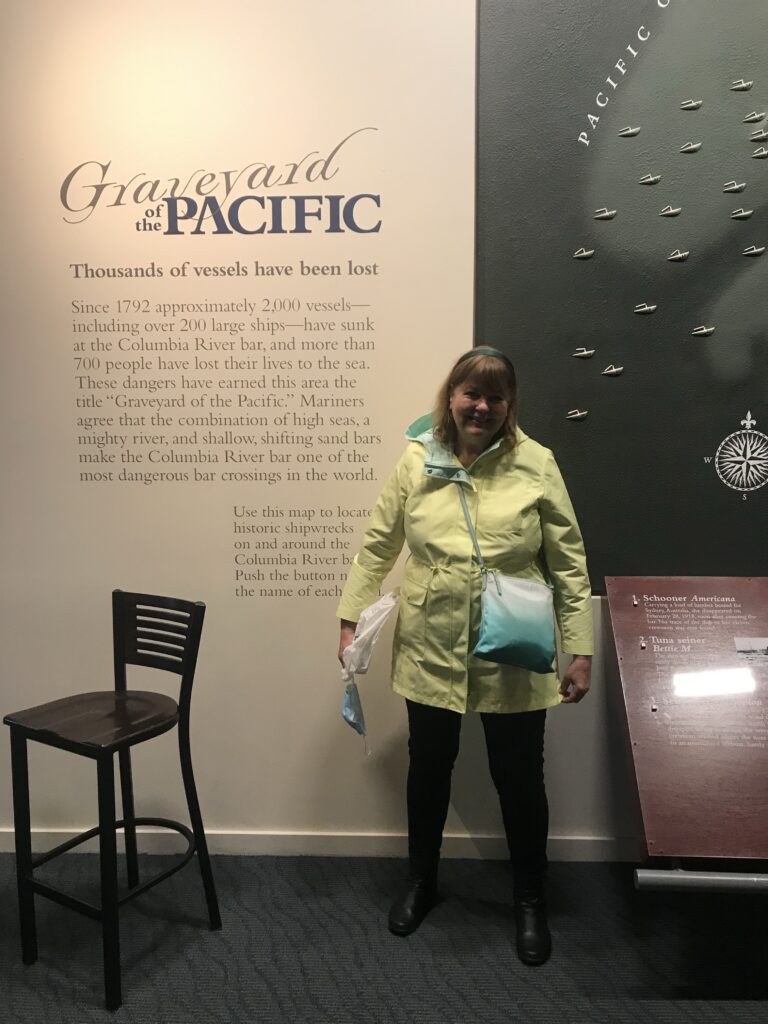

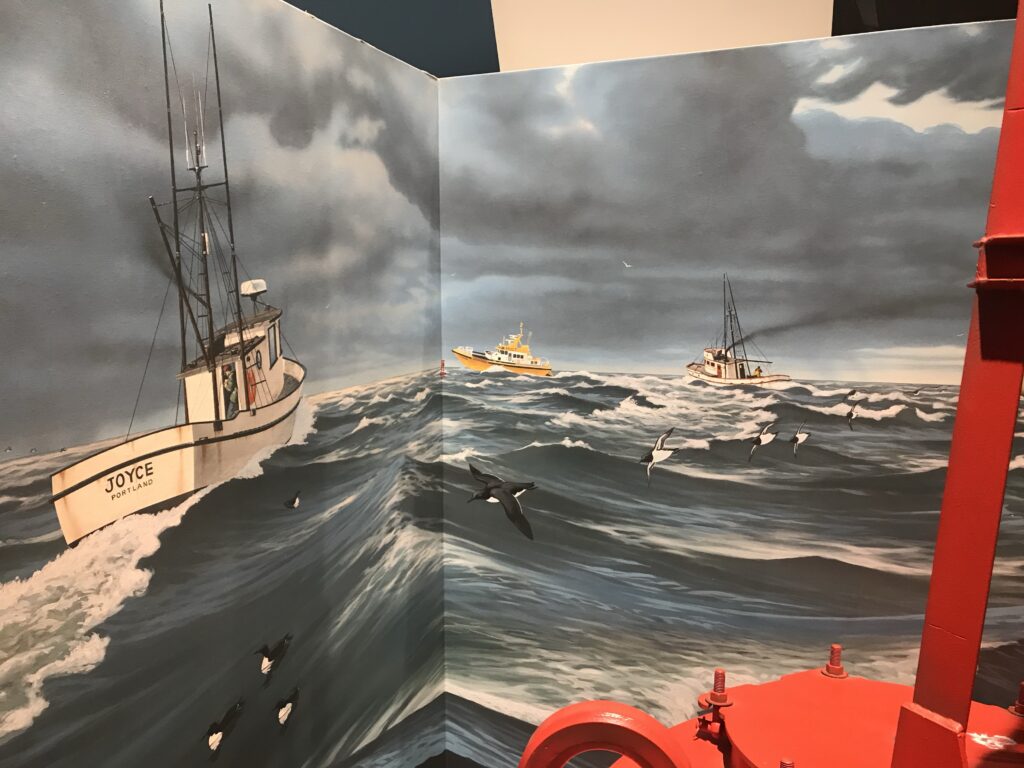

The Columbia River Maritime Museum is considered a must-see in Astoria because it vividly interprets the unique and dramatic maritime history of the Columbia River and the surrounding “Graveyard of the Pacific.” It offers insight into exploration, shipwrecks, rescue missions, navigation challenges, and river commerce—anchoring an understanding of Astoria’s pivotal role in Pacific Northwest maritime history.airial+2

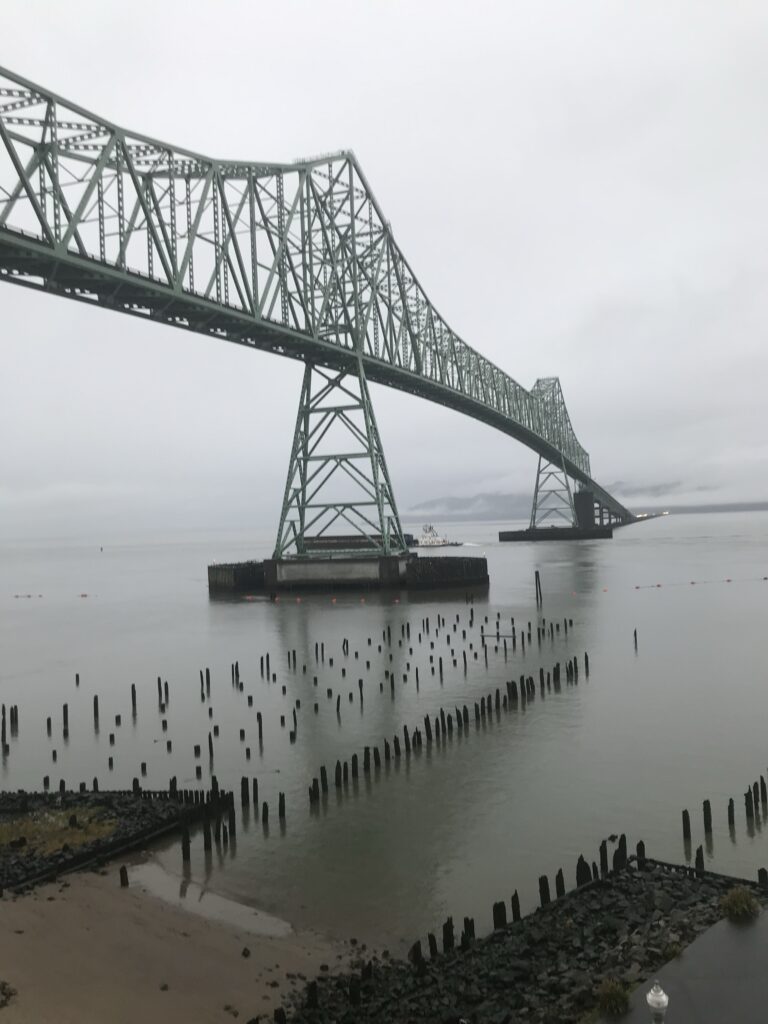

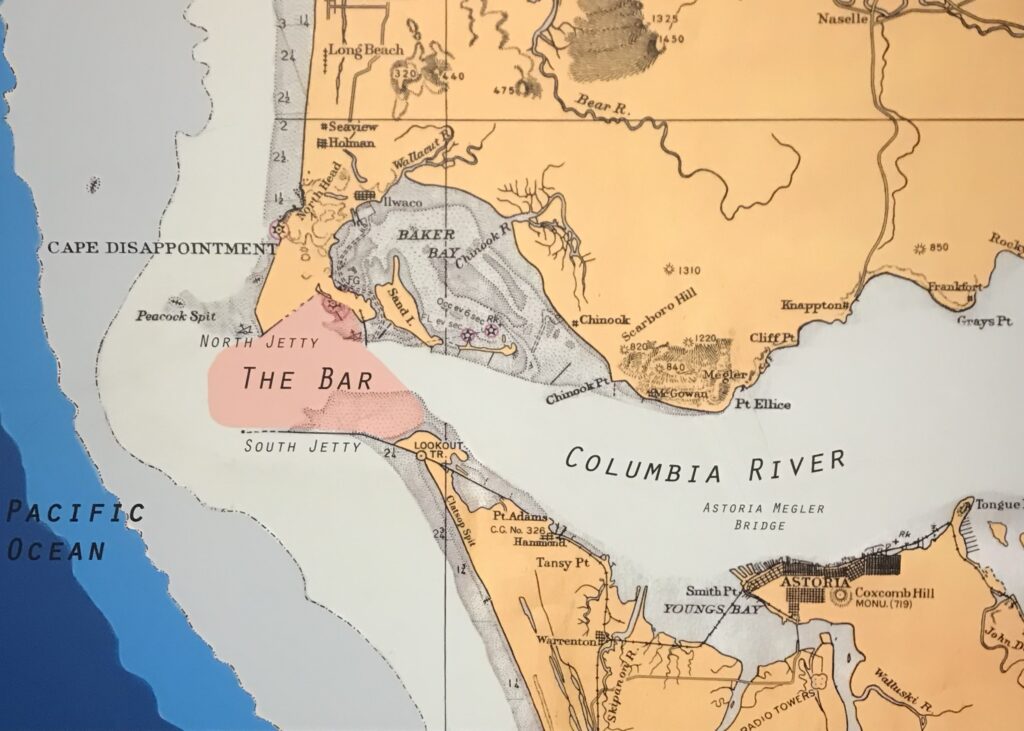

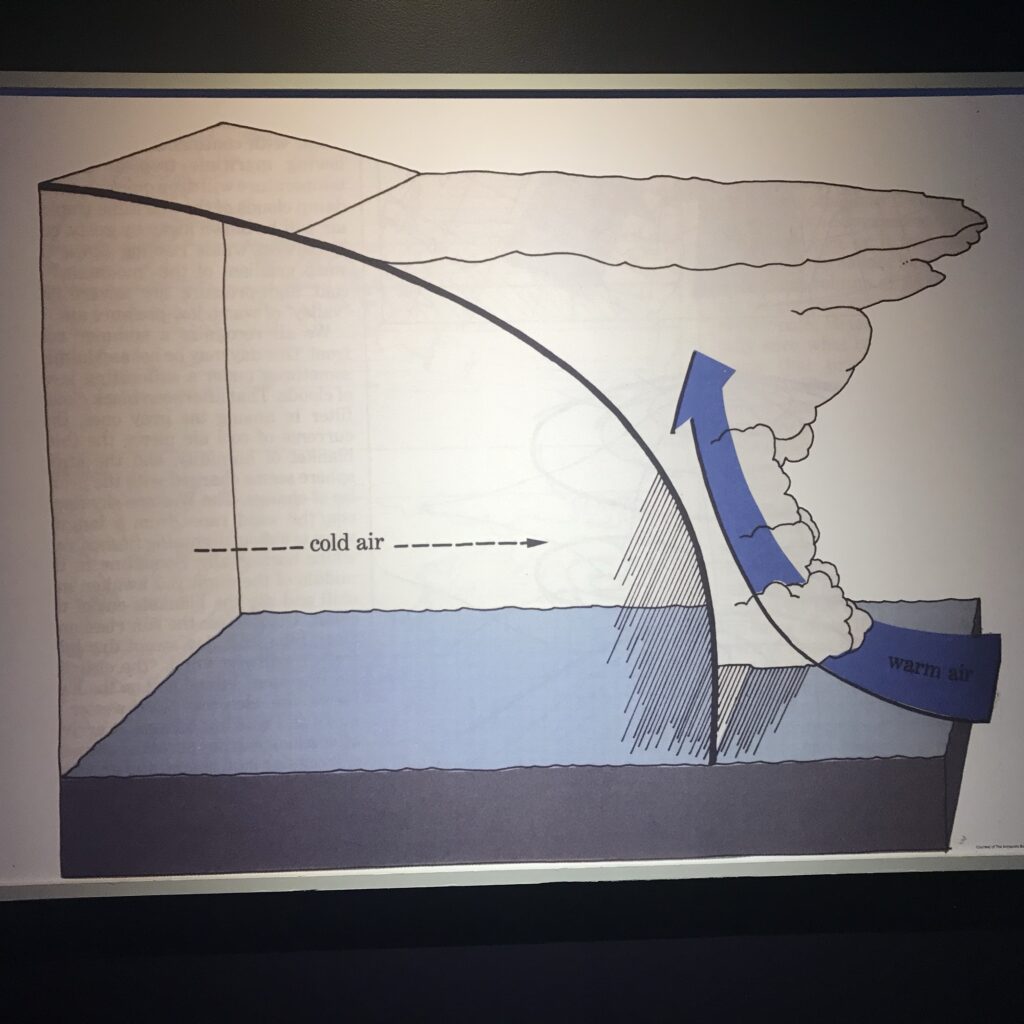

The silt and debris carried down by the fast-flowing river is slowed by its encounter with Pacific tides, depositing much of its load of sediment at the mouth of the river. These deposits form sandbars that shift with the tides and currents and create challenges to safe navigation. This shoaling, or shallowing of the river depth is referred to as the bar where the river’s flow enters the river.

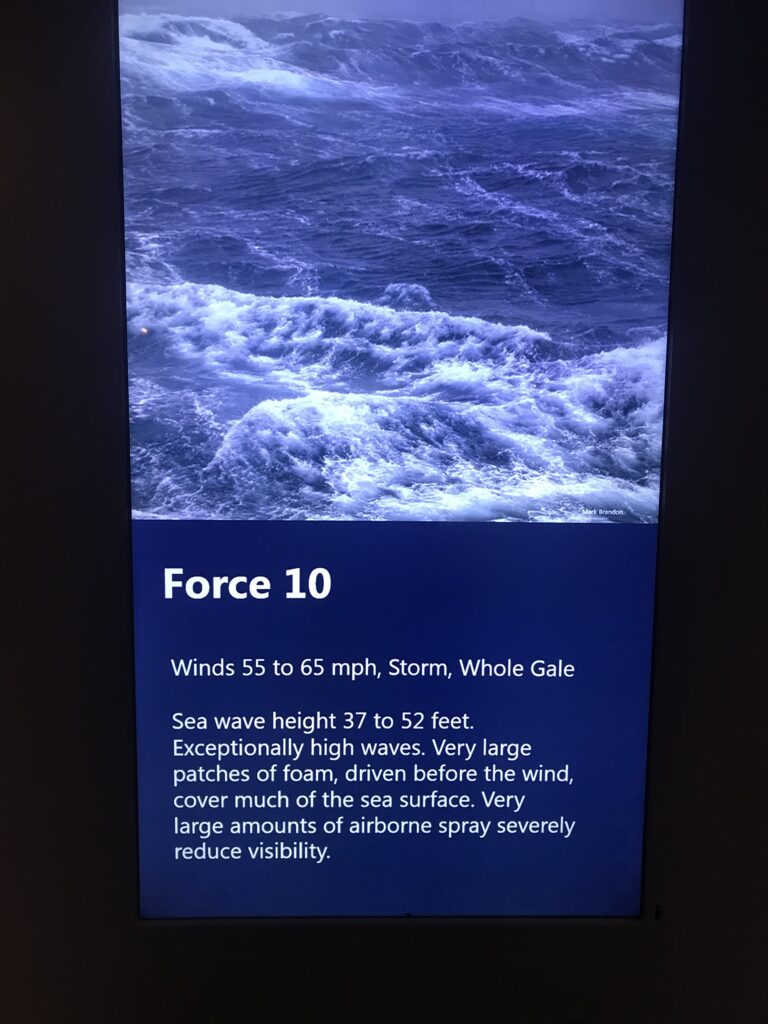

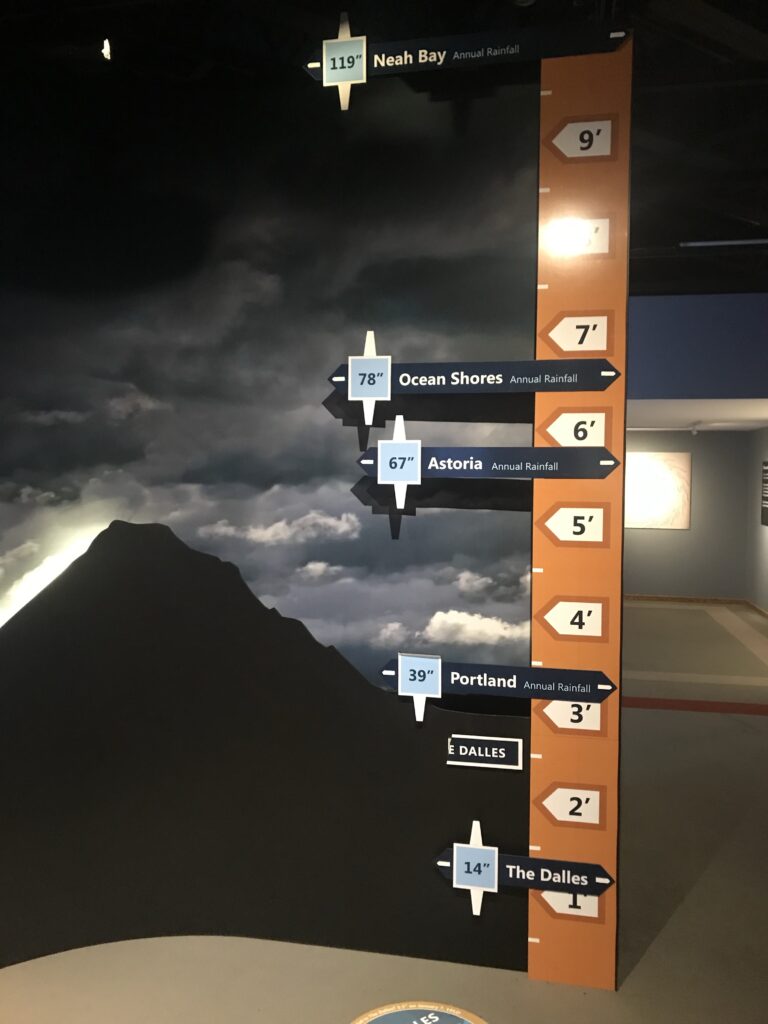

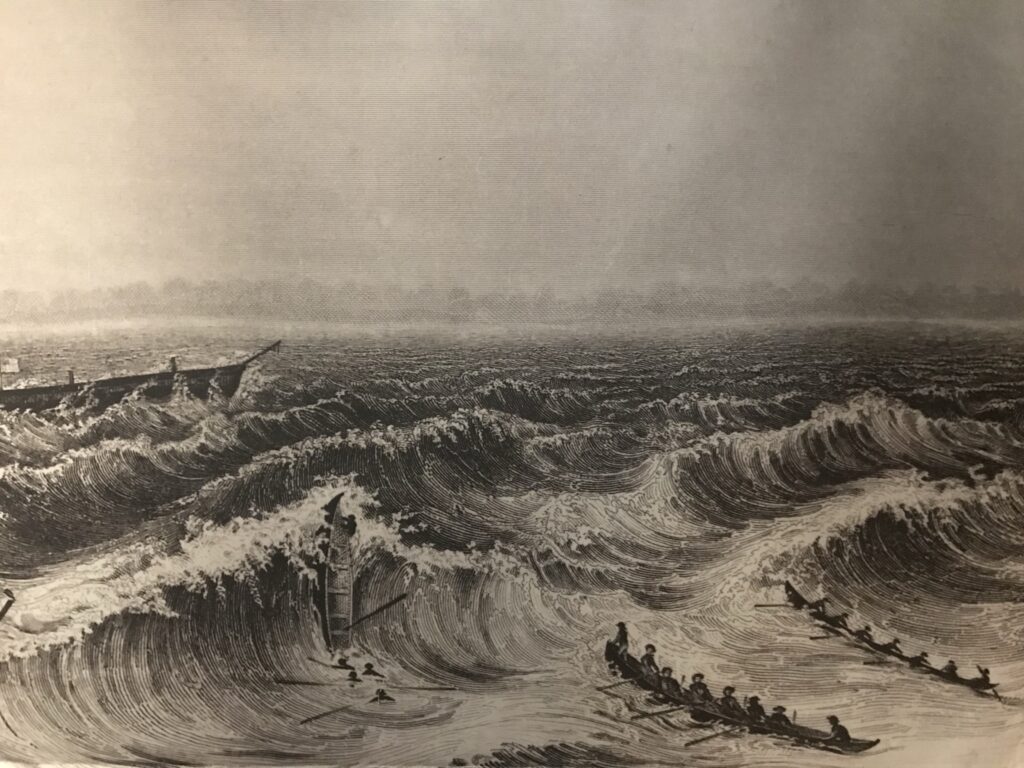

Winter storms at the Columbia River Bar create giant breaking waves, some over 40 feet tall.

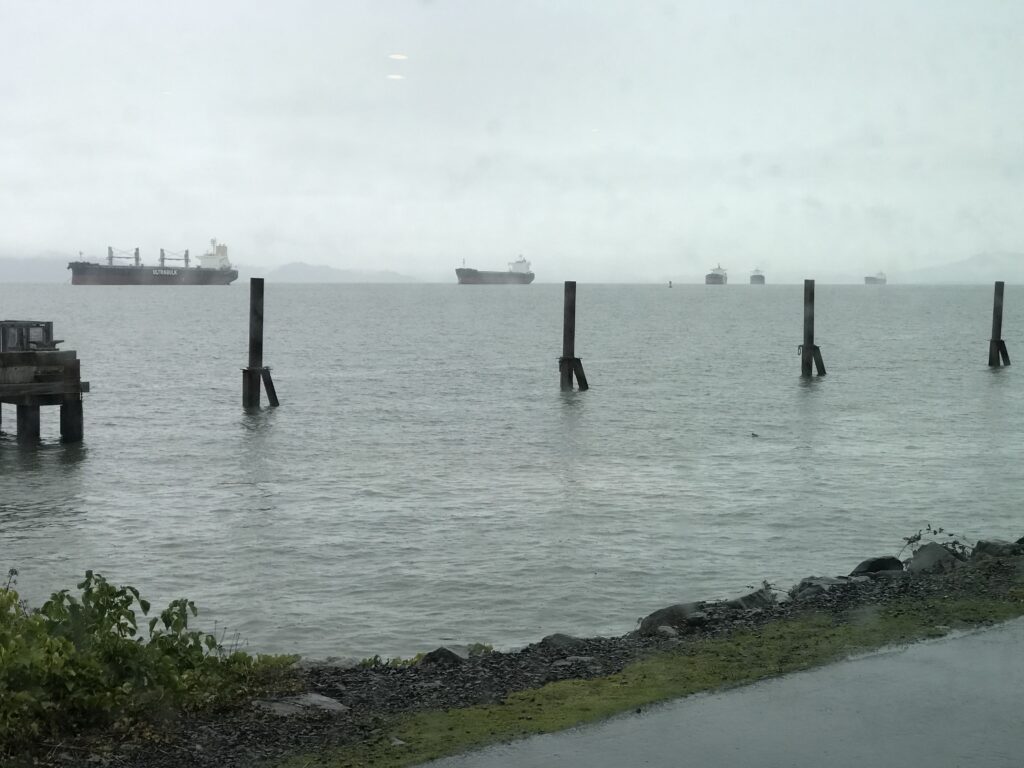

Even today’s largest cargo ships can be tossed around like bath toys in these fierce conditions.

Maritime professionals, some of the best in the world, navigate these dangerous waters daily.

Because of their skill and vigilance, crossing the bar has never been safer. Even so, the potential for disaster on the Bar is constant.

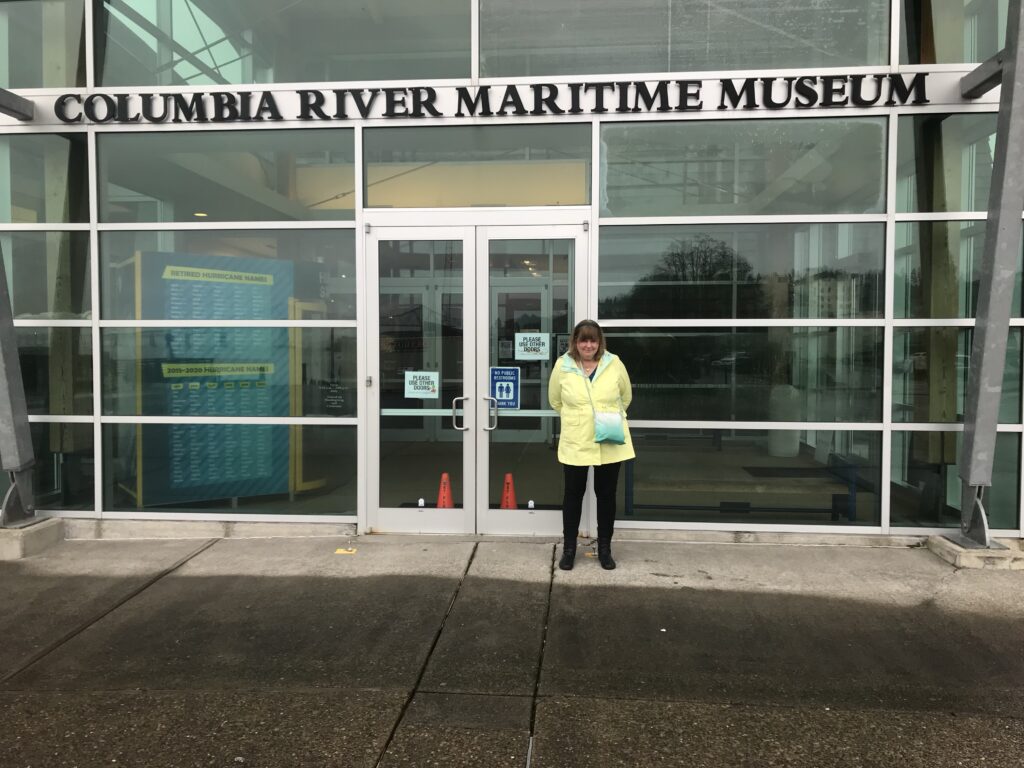

Columbia River Maritime Museum at Astoria, Oregon

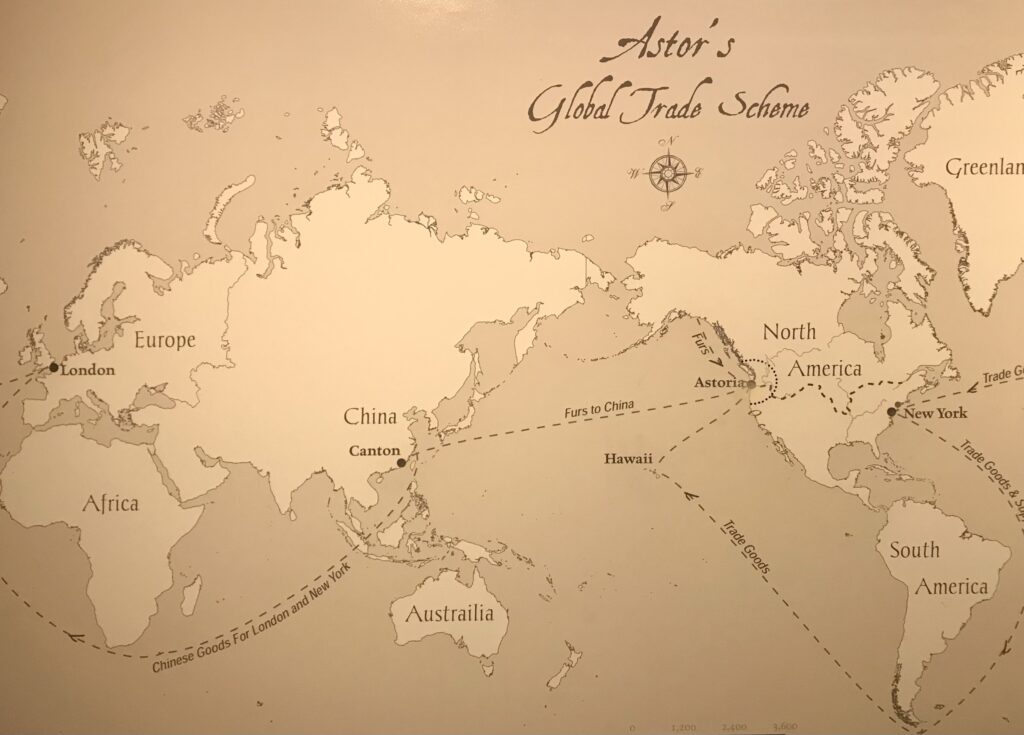

Astoria was named after John Jacob Astor who was a German-born American businessman, fur trader, and real estate magnate. His entrepreneurial vision greatly influenced the development of the Pacific Northwest.

Astor never personally visited Oregon or the Columbia River region, but his investment in the fur trade led to the founding of Astoria (initially called Fort Astoria) at the mouth of the Columbia River in 1811. His vision for Astoria was to establish it as a strategic fur trading post and gateway for a chain of fur trade outposts across western North America.

Astor intended Astoria to serve as a clearinghouse where furs from the vast Northwest could be gathered and shipped directly to lucrative markets in China, bypassing middlemen and creating a direct trade route between the American West Coast and Asia.

Astoria was the first American settlement on the Pacific coast and symbolized Astor’s ambition to expand American commercial and territorial influence westward following the Louisiana Purchase.

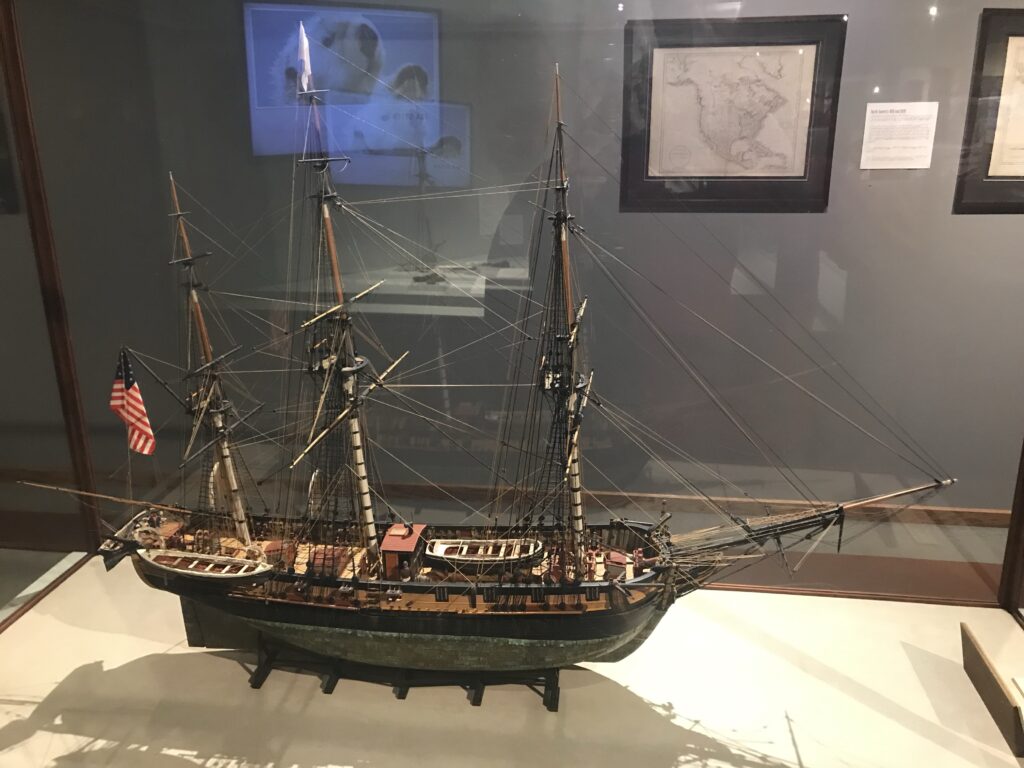

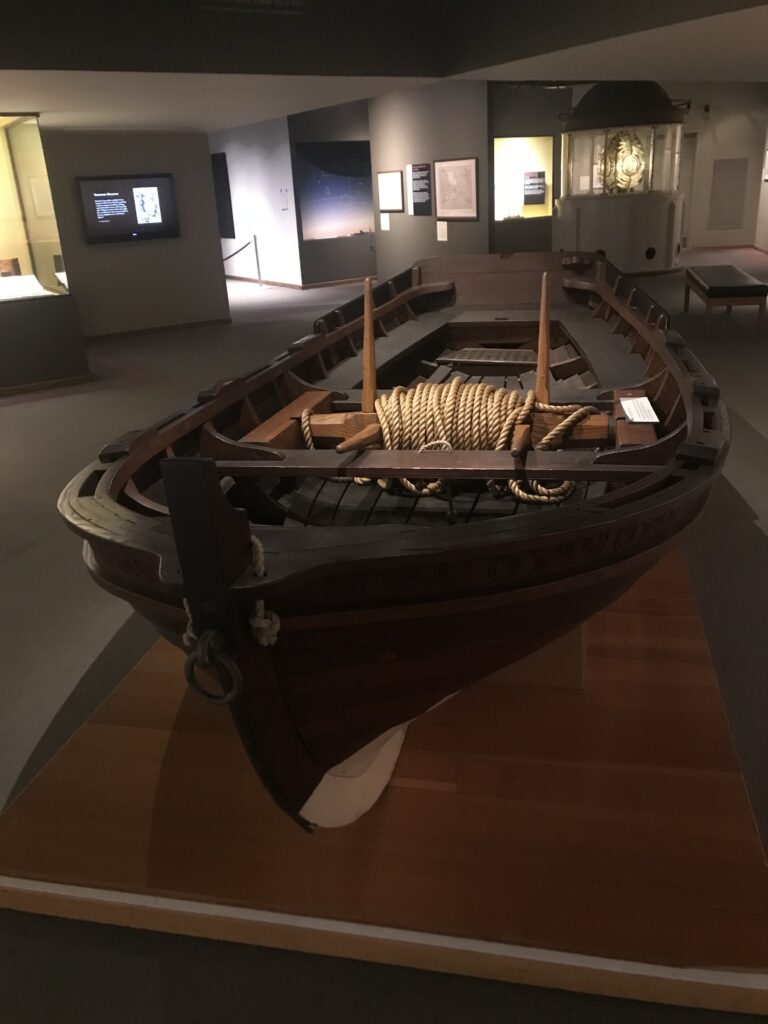

Built at New York in 1806 by Adam & Noah Brown

Length, 94′ Breadth, 25′ Depth, 13′ 269 Tons Sent by John Jacob Astor in 1810 to establish the fur trading post that later became Astoria, Oregon. The ship was destroyed by indians on the coast of Vancouver Island the following year. This 1/4 inch scale model was built by Eric Pardy, based on research by Hewitt Jackson. Presented in Honor of the National Bicentennial Gavin, Hugh’and John

Sons of the lst Baron Astor of Hever Direct Descendants of John Jacob Astor (1763-1848)

Through his Pacific Fur Company, Astor sought to compete with established British fur companies and to assert U.S. presence in the Oregon Country. Despite early success, the War of 1812 disrupted Astor’s plans; the outpost was sold to the British North West Company in 1813, but the establishment of Astoria laid the groundwork for later American claims that contributed to the Oregon Treaty of 1846.

Astor’s vision combined commercial expansion, territorial ambition, and strategic trade positioning, marking him as a pioneering figure in the economic and geopolitical development of the American West.[1][2][4][5]

Core Exhibits and Significance

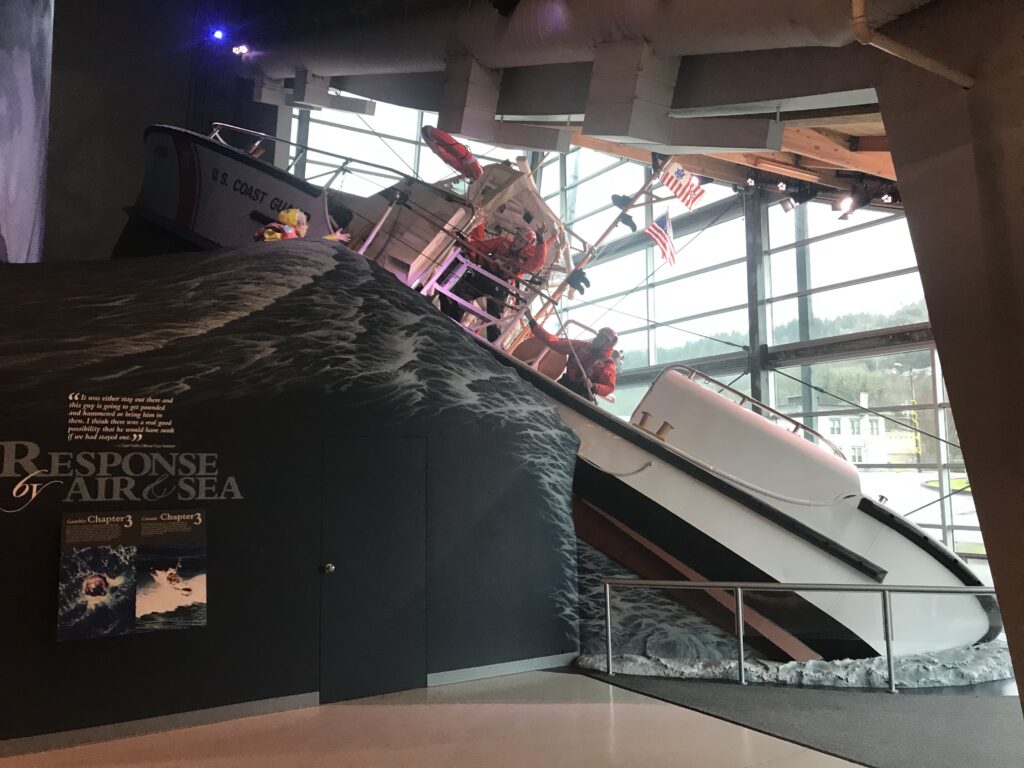

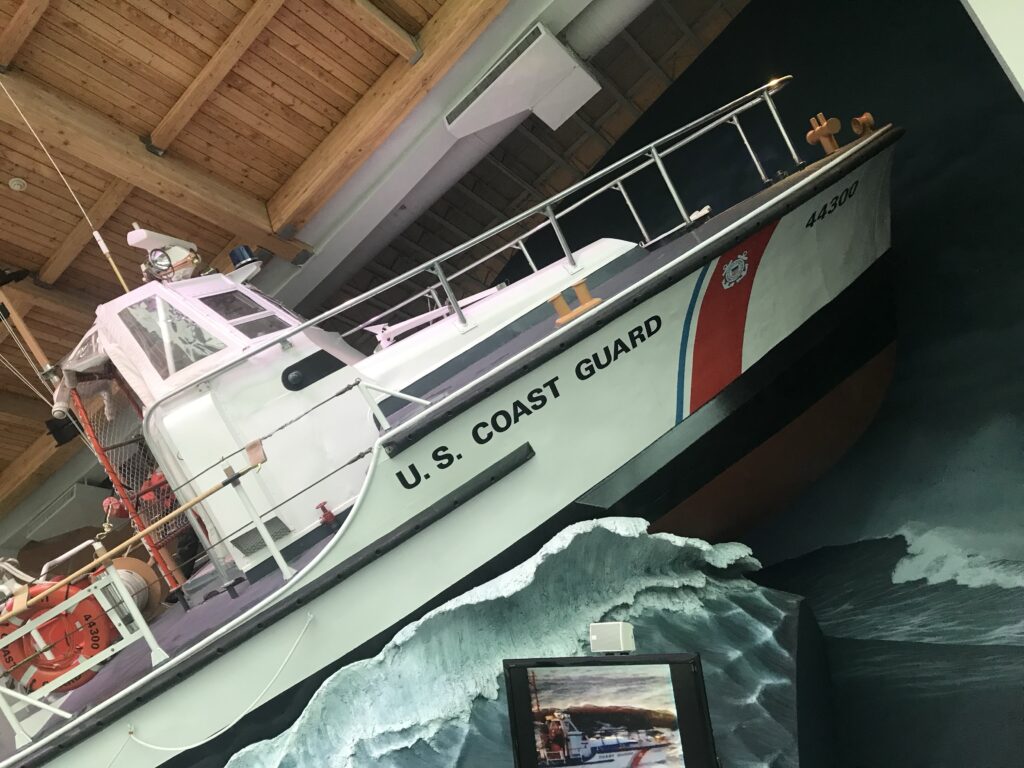

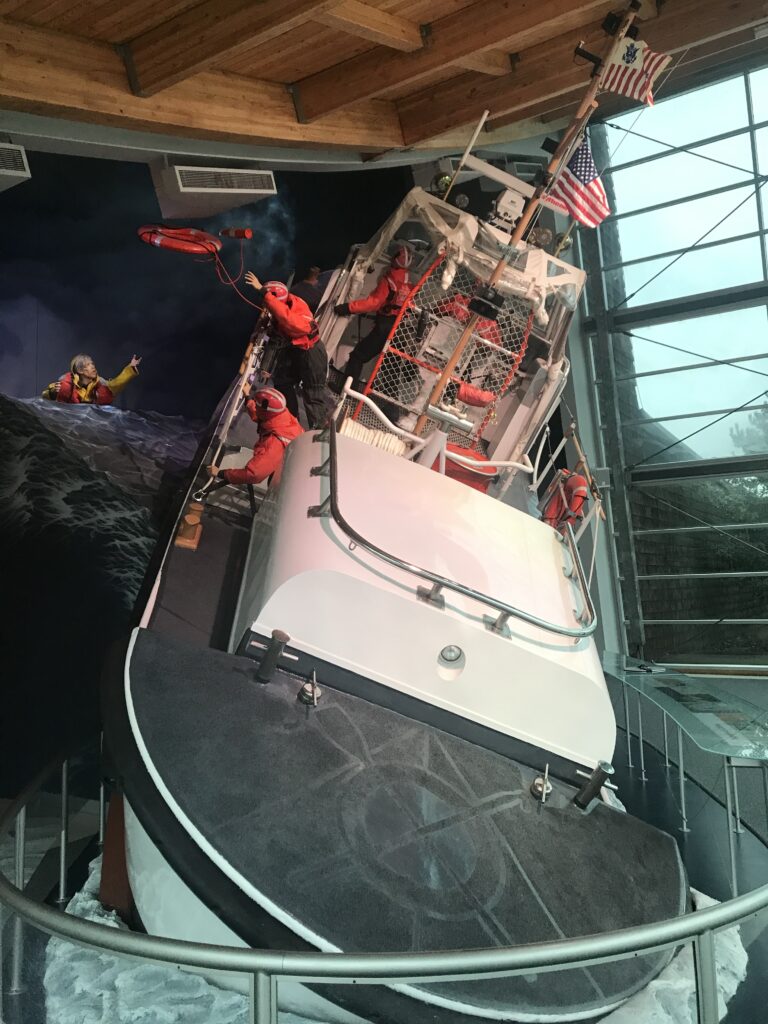

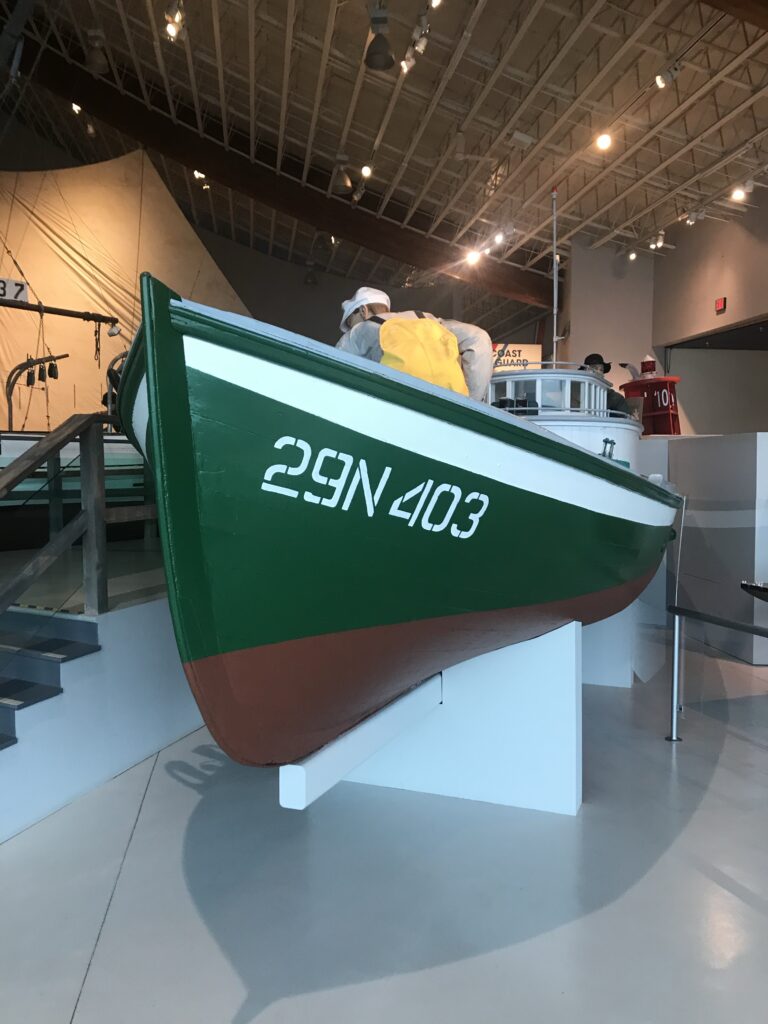

- The museum highlights the perils of the Columbia River Bar, notorious for its shipwrecks and danger—earning its moniker “Graveyard of the Pacific.” Interactive exhibits and dramatic dioramas, such as a Coast Guard boat engaged in heavy seas, bring these stories to life and underscore the region’s treacherous maritime environment.crmm+1

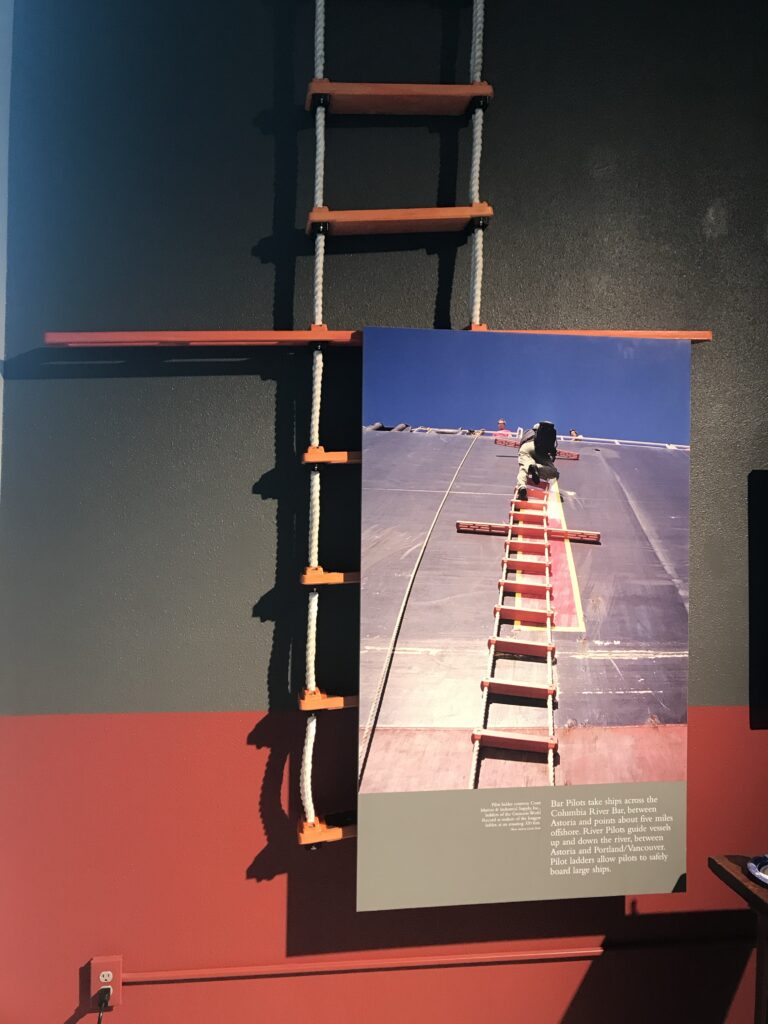

- Maritime innovation, including the work of pilots and the Coast Guard, is a central theme. Visitors can explore genuine artifacts and immersive displays illustrating both historical and modern river navigation and rescue.airial+1

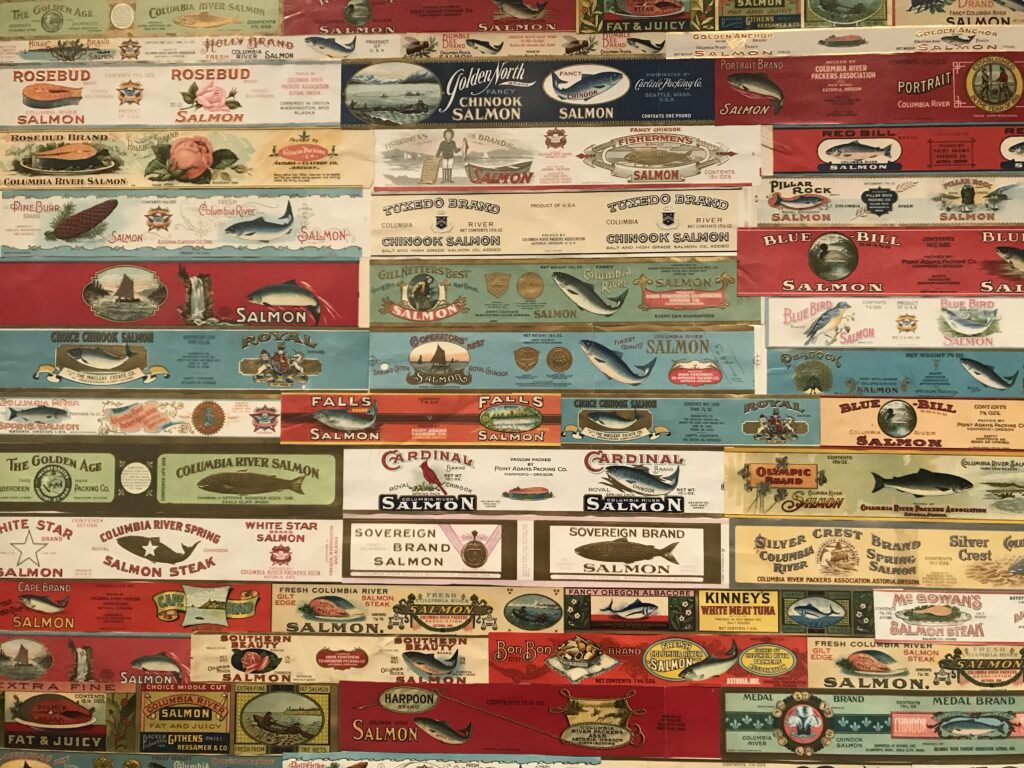

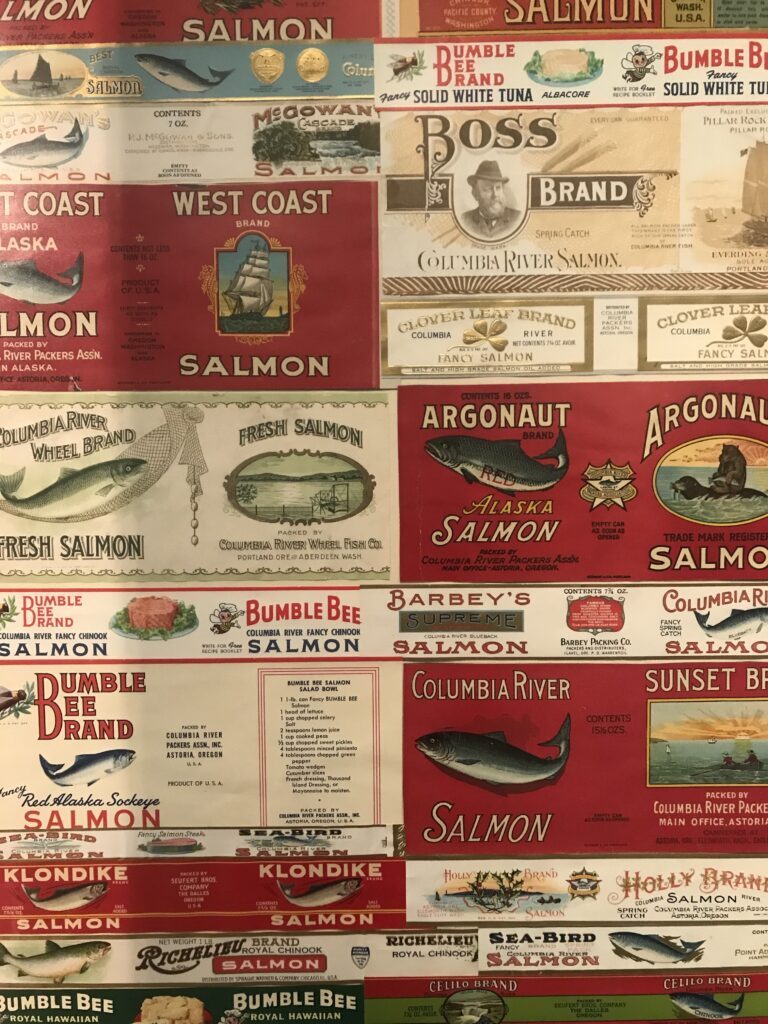

- The Indigenous presence and Chinook culture, as well as the heyday of salmon fishing, are also thoroughly portrayed, tying together natural resources, human history, and industry.traveloregon+1

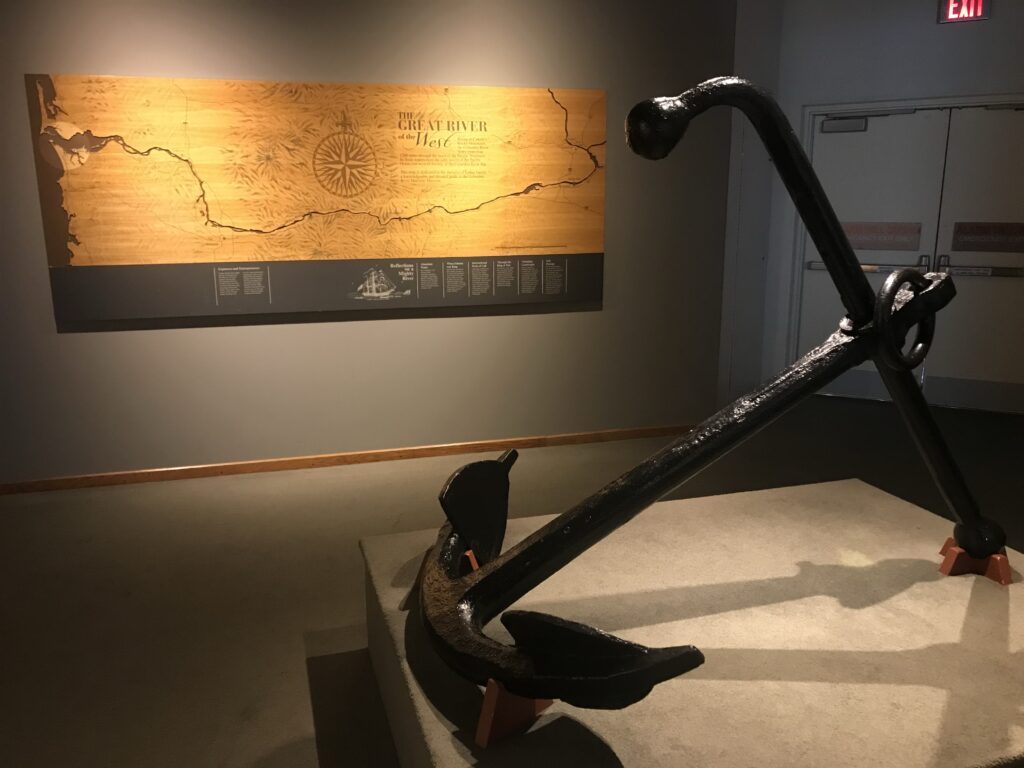

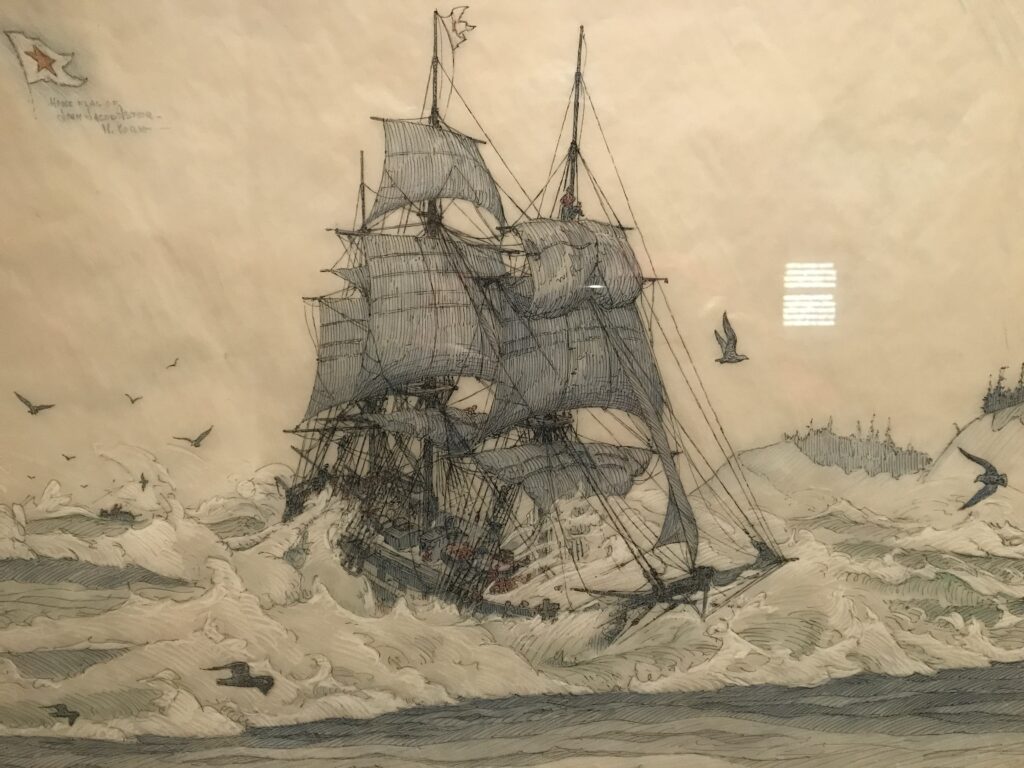

Robert Gray and the Naming of the Columbia

The museum provides context on Captain Robert Gray, the American merchant captain who, in May 1792, became the first recorded American to navigate the Columbia River. His ship, the Columbia Rediviva, gave the river its name and solidified U.S. regional claims. The museum chronicles this event, among other expedition milestones.crmm+1

The Columbia Rediviva was fitted out in Boston for the maritime fur trade with Asia. Her owners, a consortium led by Joseph Barrell, equipped the vessel with goods for bartering, such as ironware, textiles, axes, and trinkets, which would be exchanged for sea otter pelts along the Northwest Coast. These pelts, highly prized in China, could in turn be traded for tea, silk, and porcelain on the return leg to Boston.

Columbia Rediviva typically sailed alongside the sloop Lady Washington. On the first voyage (1787–1790), John Kendrick served as senior captain and Robert Gray as his lieutenant; Gray would later command Columbia on the iconic second voyage when the ship entered and named the Columbia River.

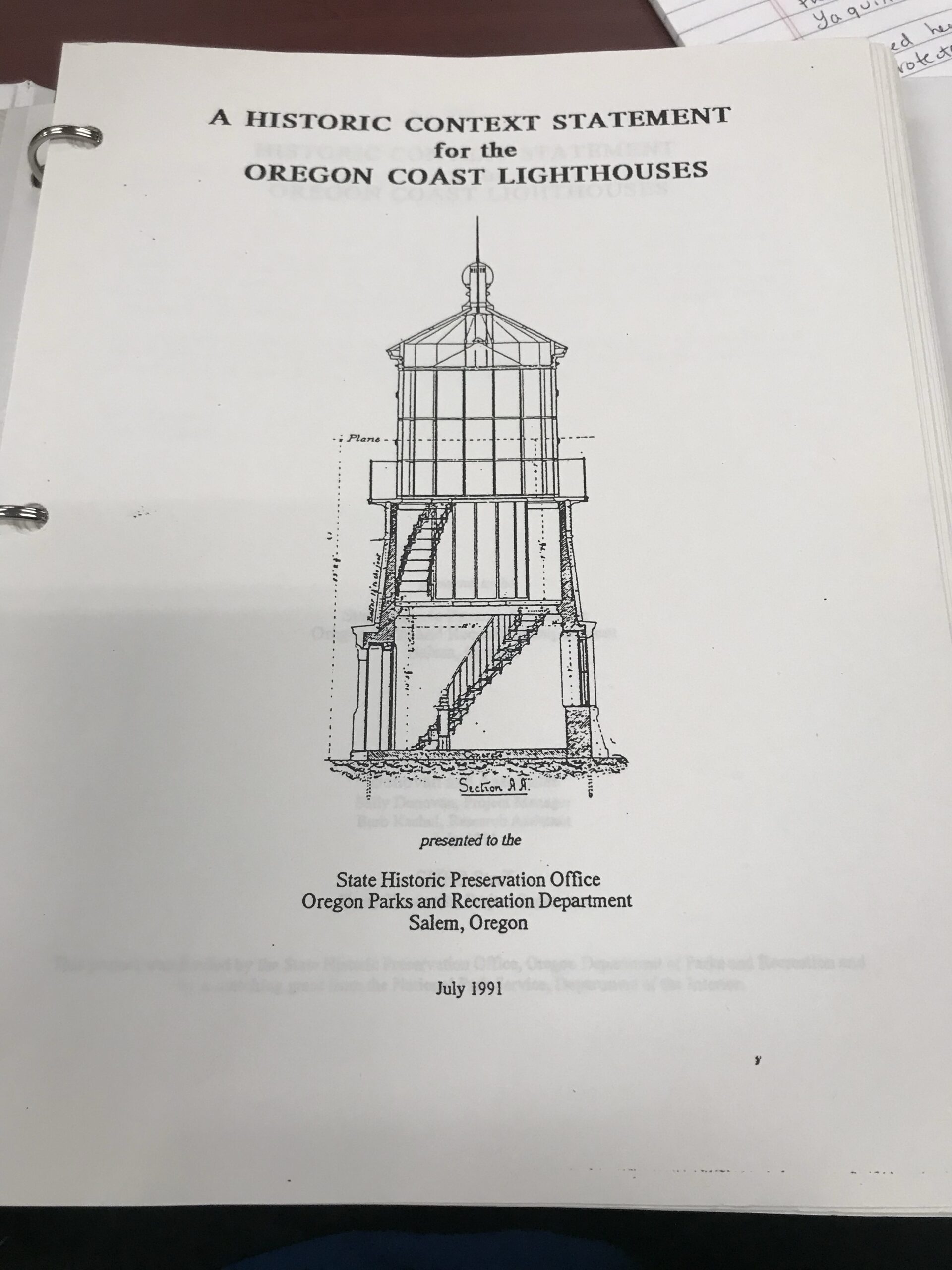

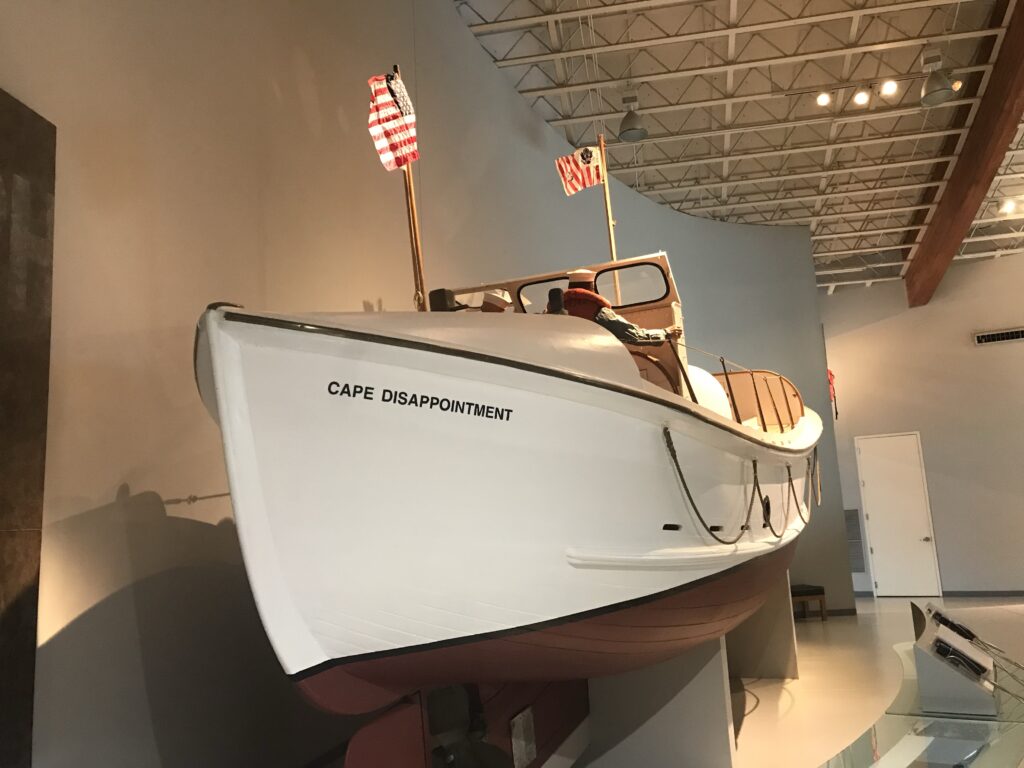

Graveyard of the Pacific, Lighthouses, and Lifeboats

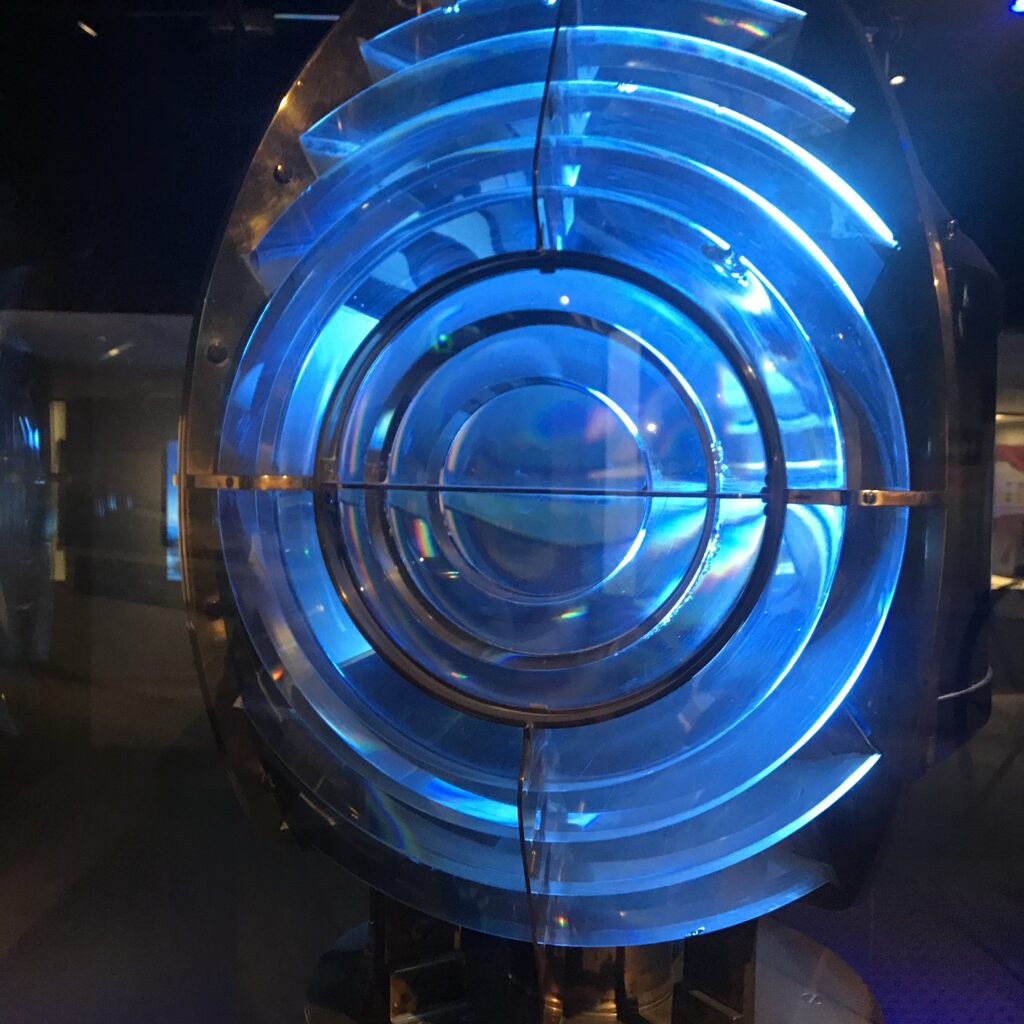

Exhibits explain the history and function of area lighthouses, including Desdemona Sands, Cape Disappointment, North Head, and lightships such as the Lightship Columbia—a floating lighthouse permanently docked as a walk-on exhibit. Artifacts like original fog bells and buoy markers are also on display.uslhs+1

Detailed dioramas and real vessels, including a 44-foot Coast Guard motor lifeboat and a planned display of the 52-foot TRIUMPH, tell the stories of daring rescue missions and the unique lifeboat culture that developed to address the area’s hazards.facebook+1

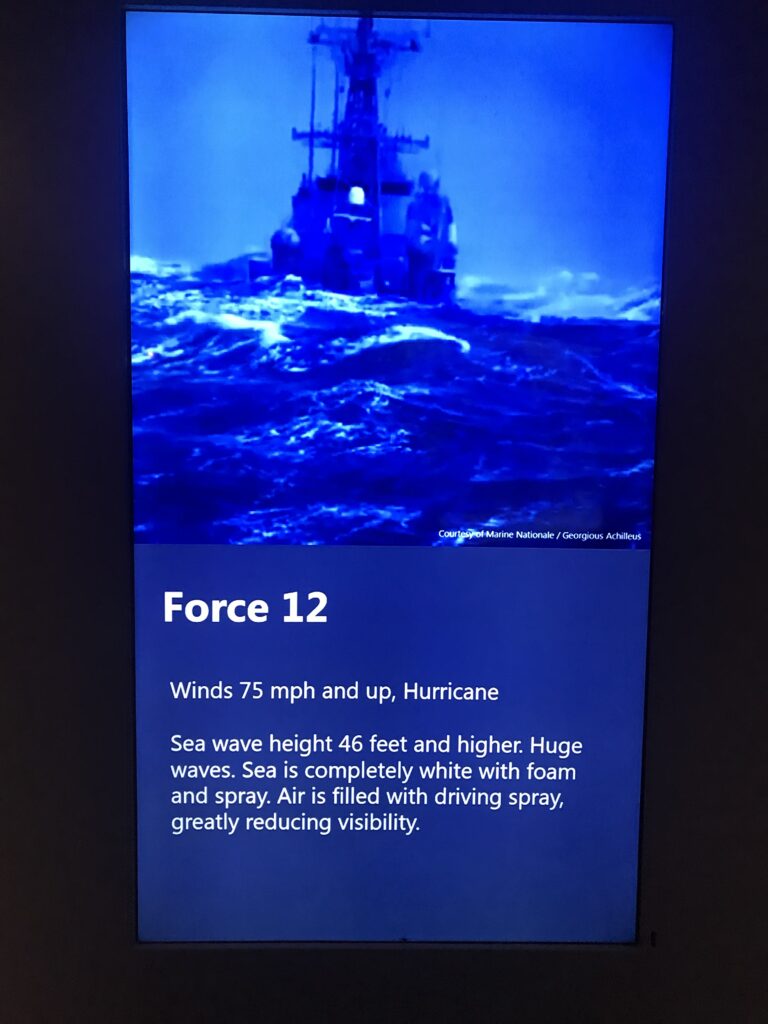

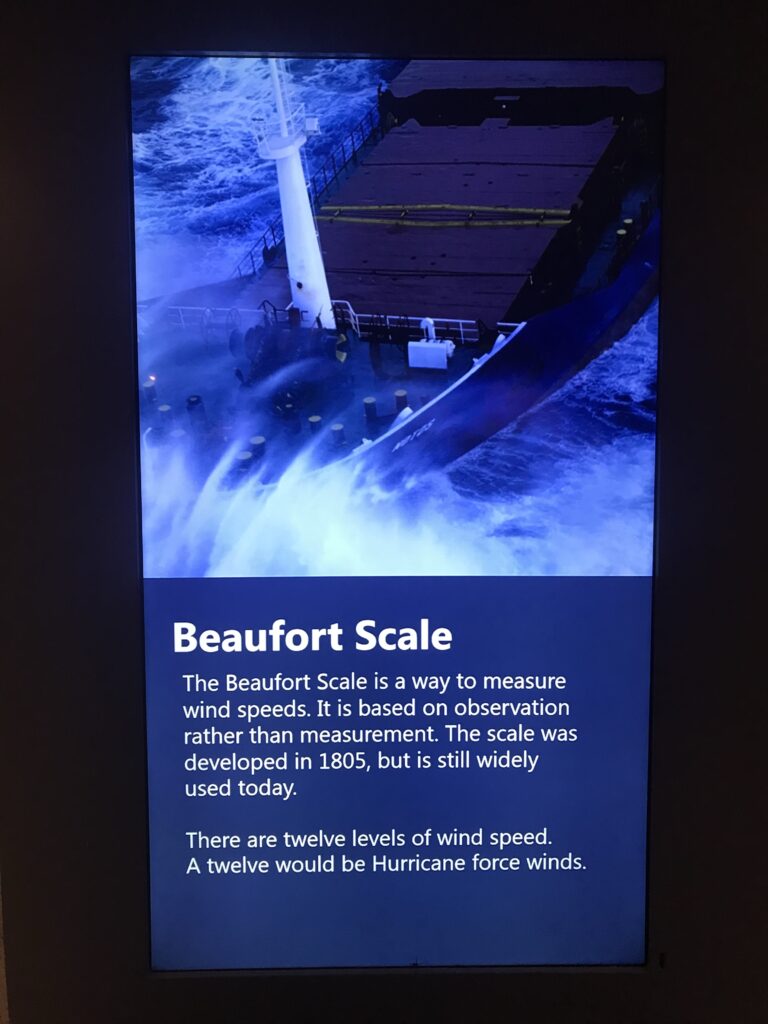

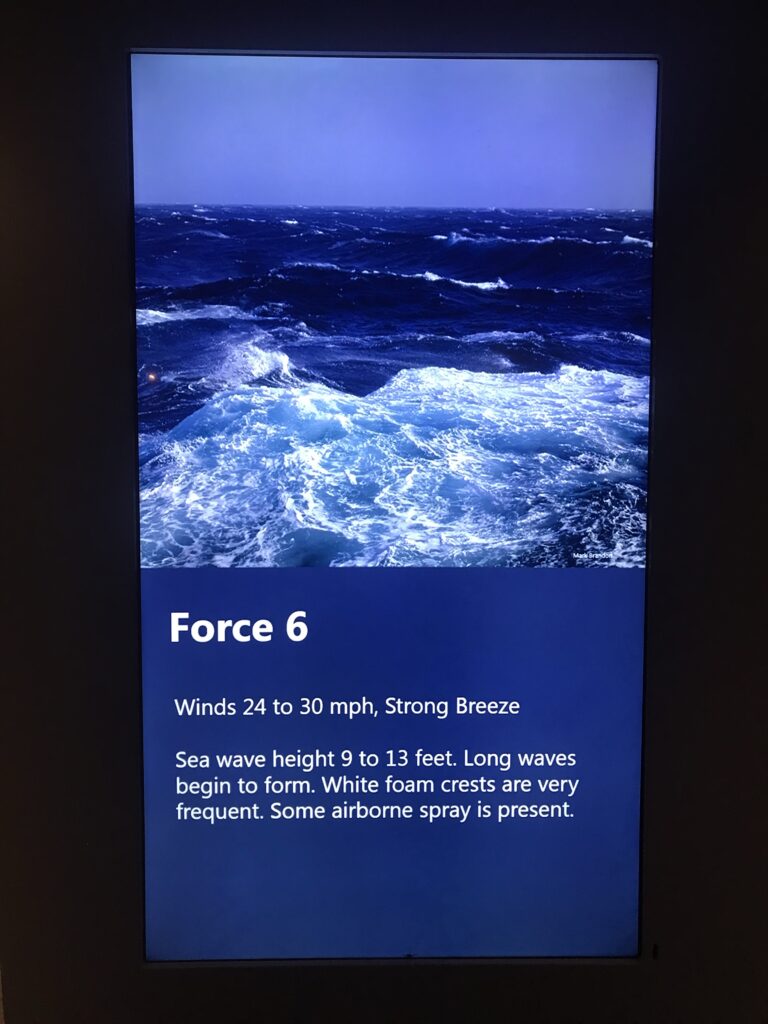

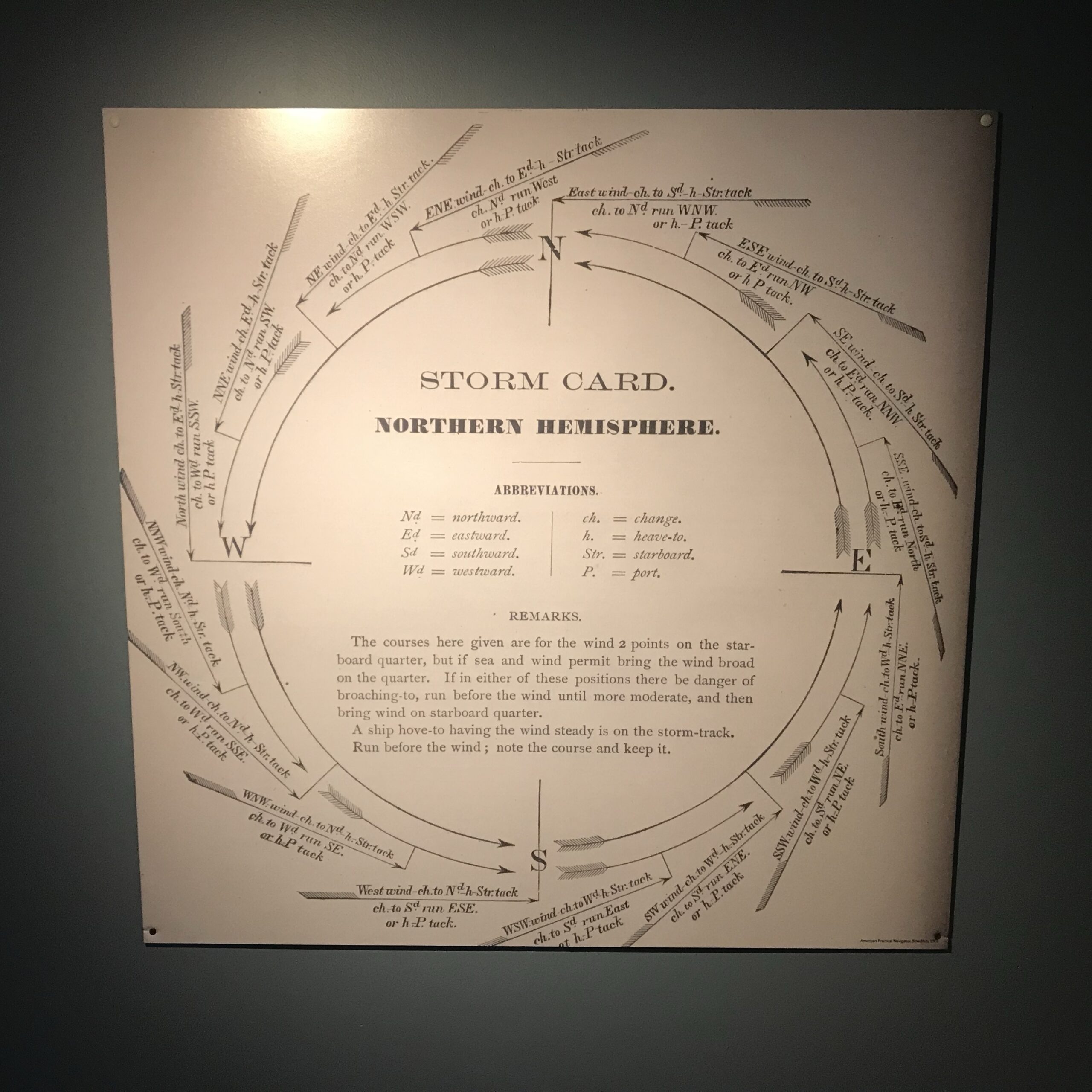

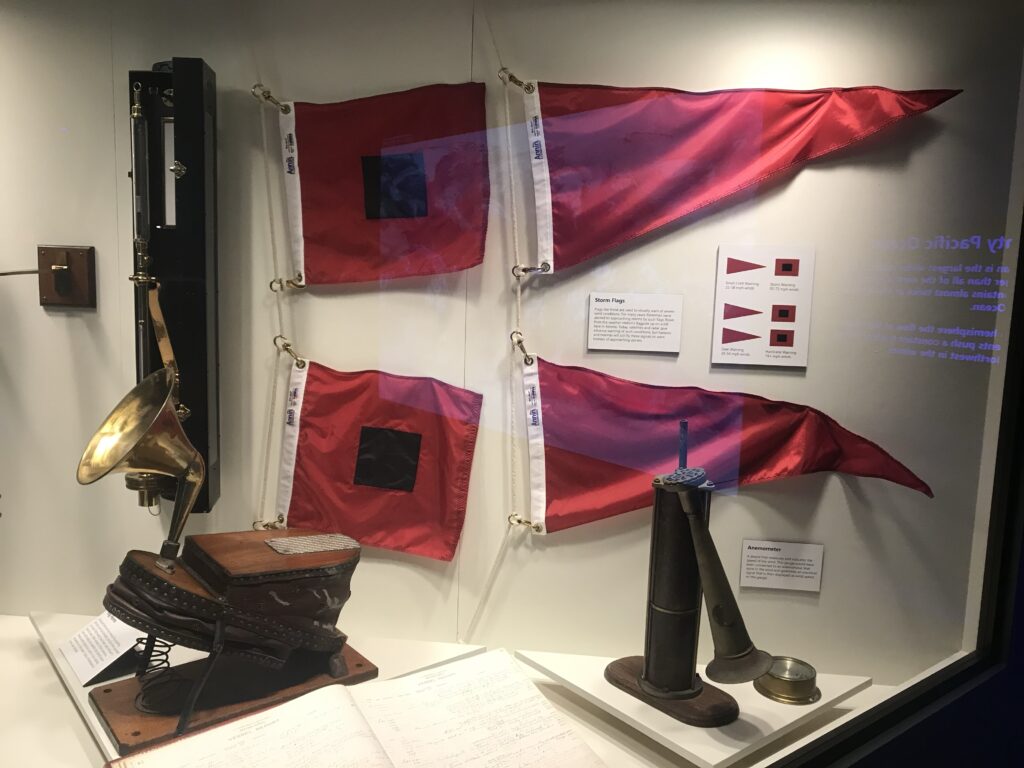

Beaufort Scale and Weather

- The museum offers interpretive content on the maritime environment, including storm conditions and the Beaufort scale—a risk and weather scale measuring wind intensity at sea. Visitors can learn how mariners would interpret this crucial scale during navigation and rescues.traveloregon

The Beaufort scale is an empirical system that assigns a number to wind force, ranging from 0 for calm to 12 for hurricane-force winds, with corresponding descriptions of sea state and observable effects on land.

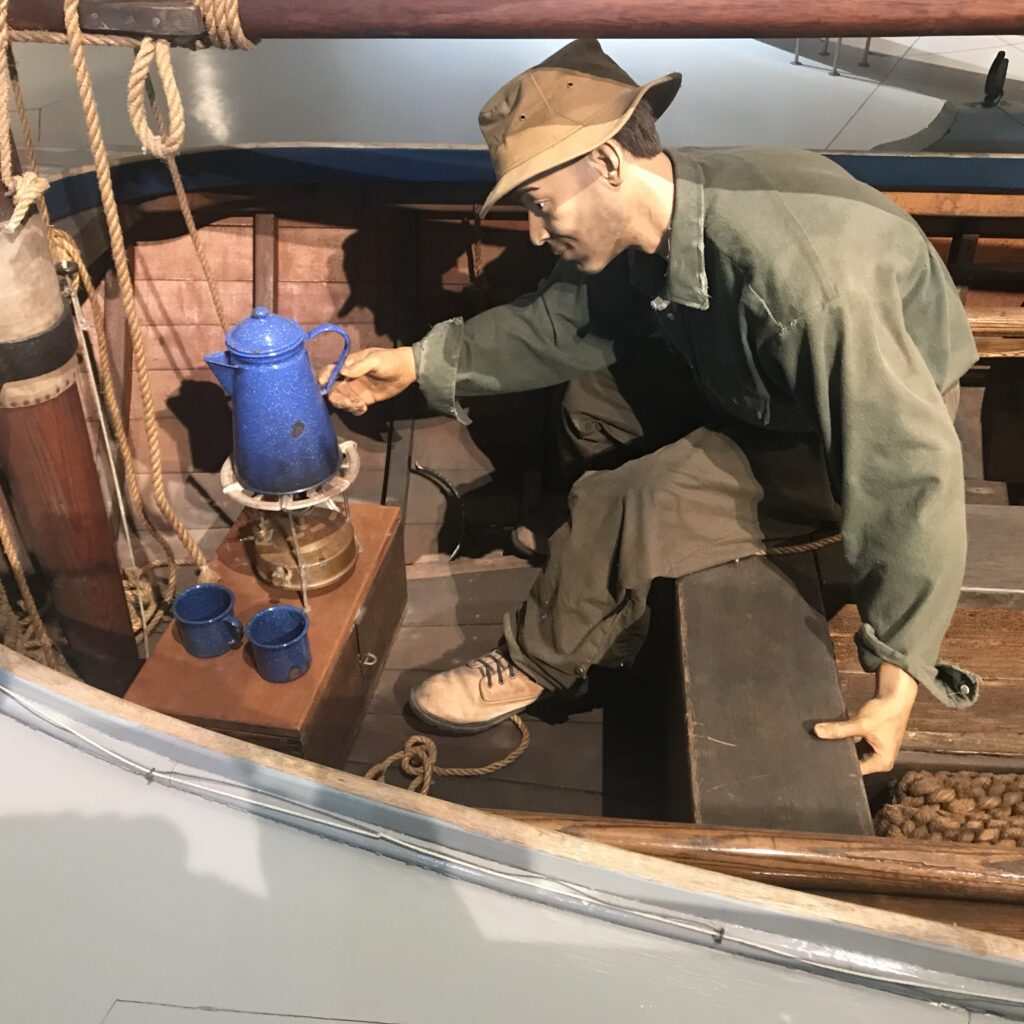

You cannot teach anyone gillnetting. You have to do that by experience. For the simple reason you have different tides, different drifts. Every drift and tide coincides with the fishing or gillnetting.

—Gunnar Hermanson

- At Beaufort number 0, the conditions are calm, with wind speeds less than 1 knot or 1 mph, the sea appears like a mirror, and smoke rises vertically without disturbance. With a Beaufort number of 1, defined as “light air,” wind speeds are 1–3 knots or 1–3 mph, forming tiny ripples on the water with no foam crests visible, and on land only smoke drift shows the wind’s direction, not even a weather vane.

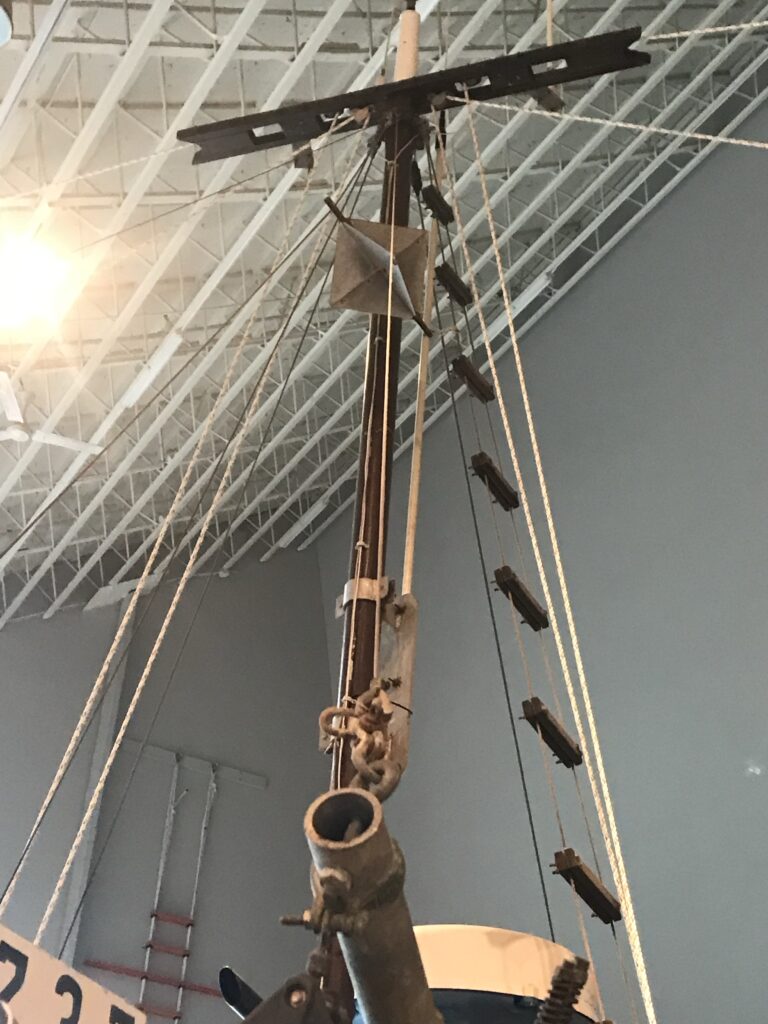

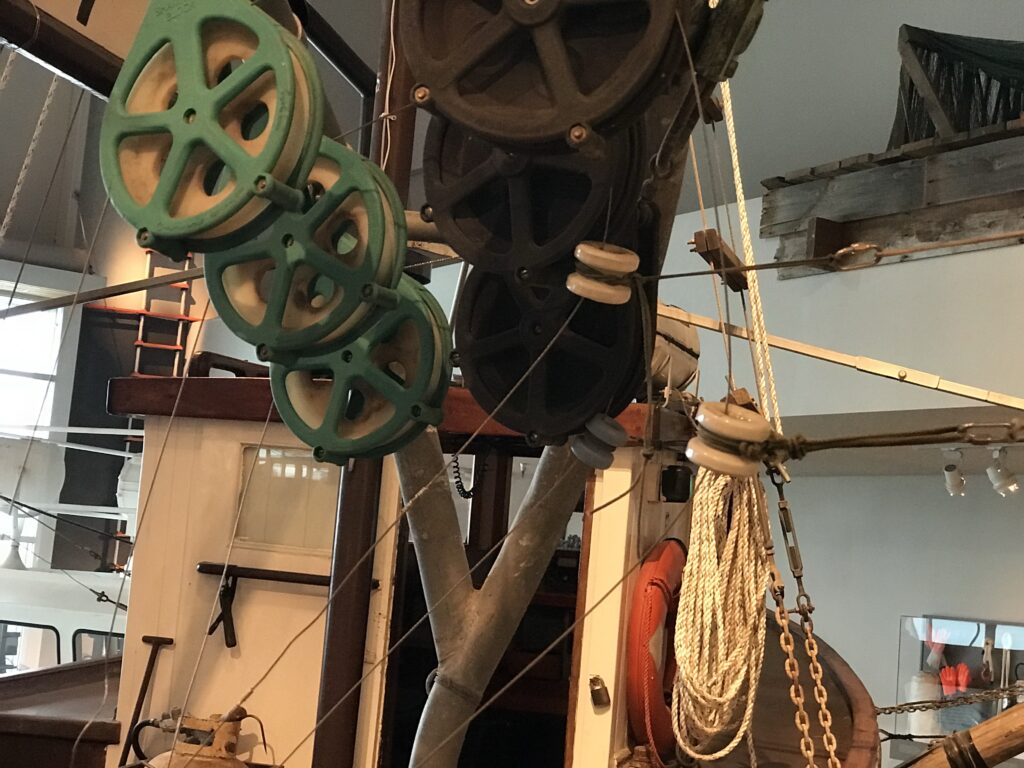

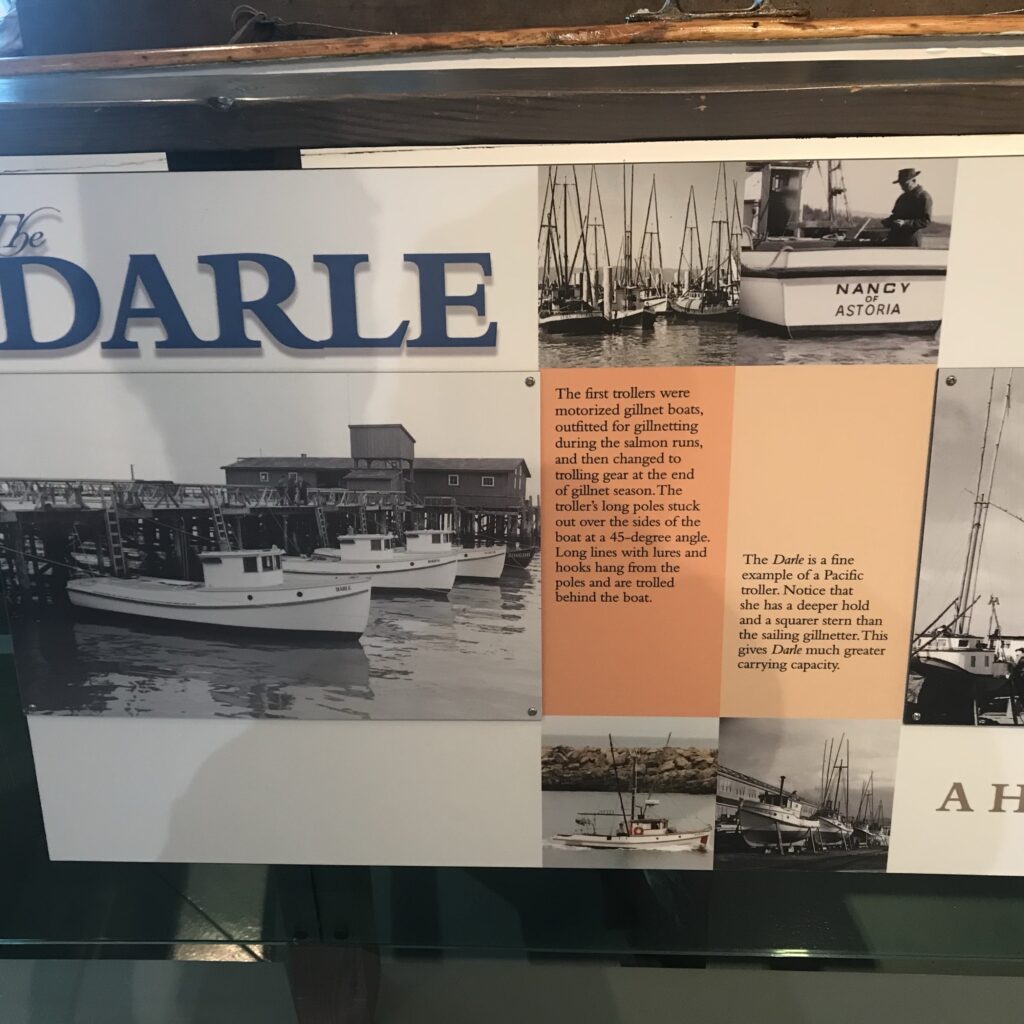

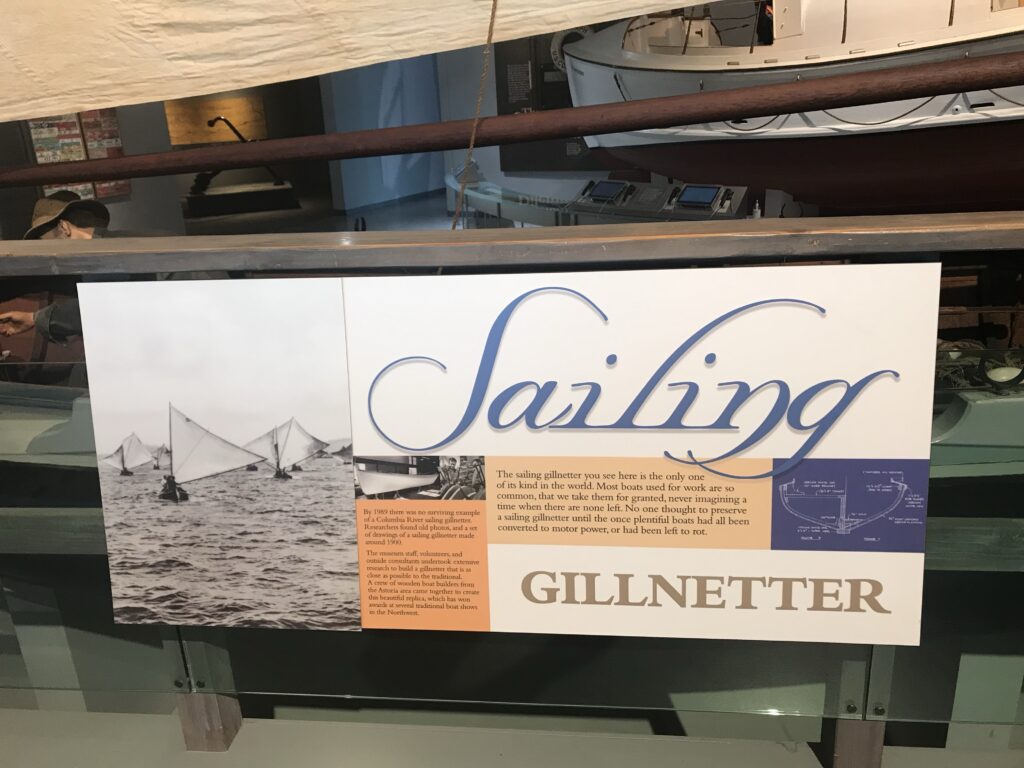

The first trollers were motorized gillnet boats, outfitted for gillnetting during the salmon runs, and then changed to trolling gear at the end of gillnet season. The troller’s long poles stuck out over the sides of the boat at a 45-degree angle. Long lines with lures and hooks hang from the poles and are trolled behind the boat.

.

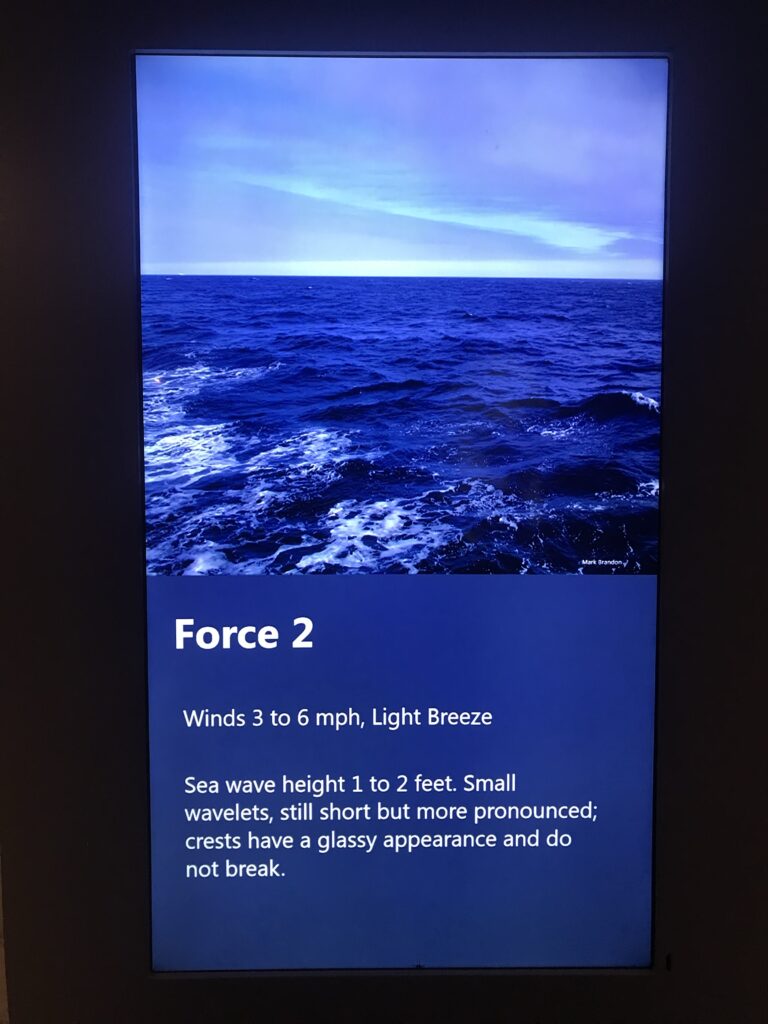

- At Beaufort number 2, the wind is called a “light breeze,” with speeds of 4–6 knots (4–7 mph). Small wavelets appear, with crests still glassy and not breaking, while on land the wind is just felt on the face and leaves begin to rustle.

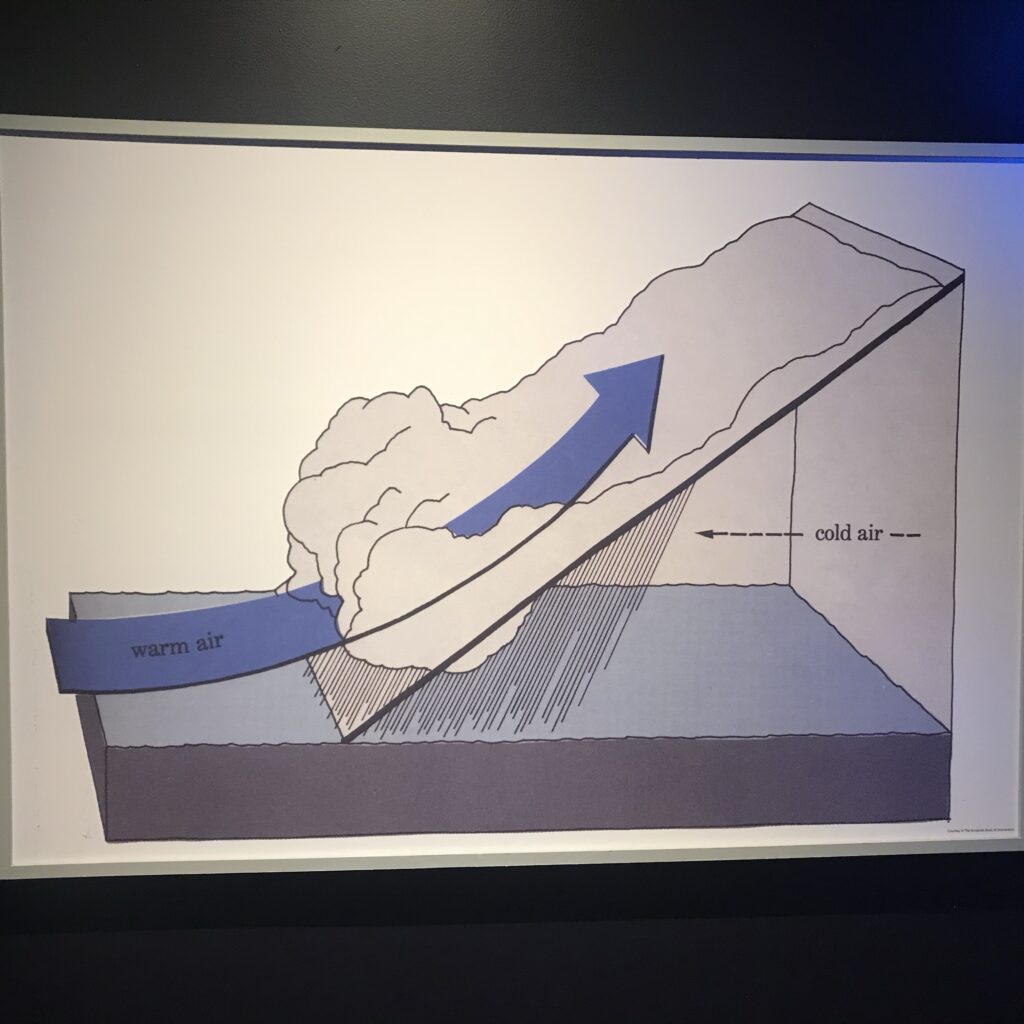

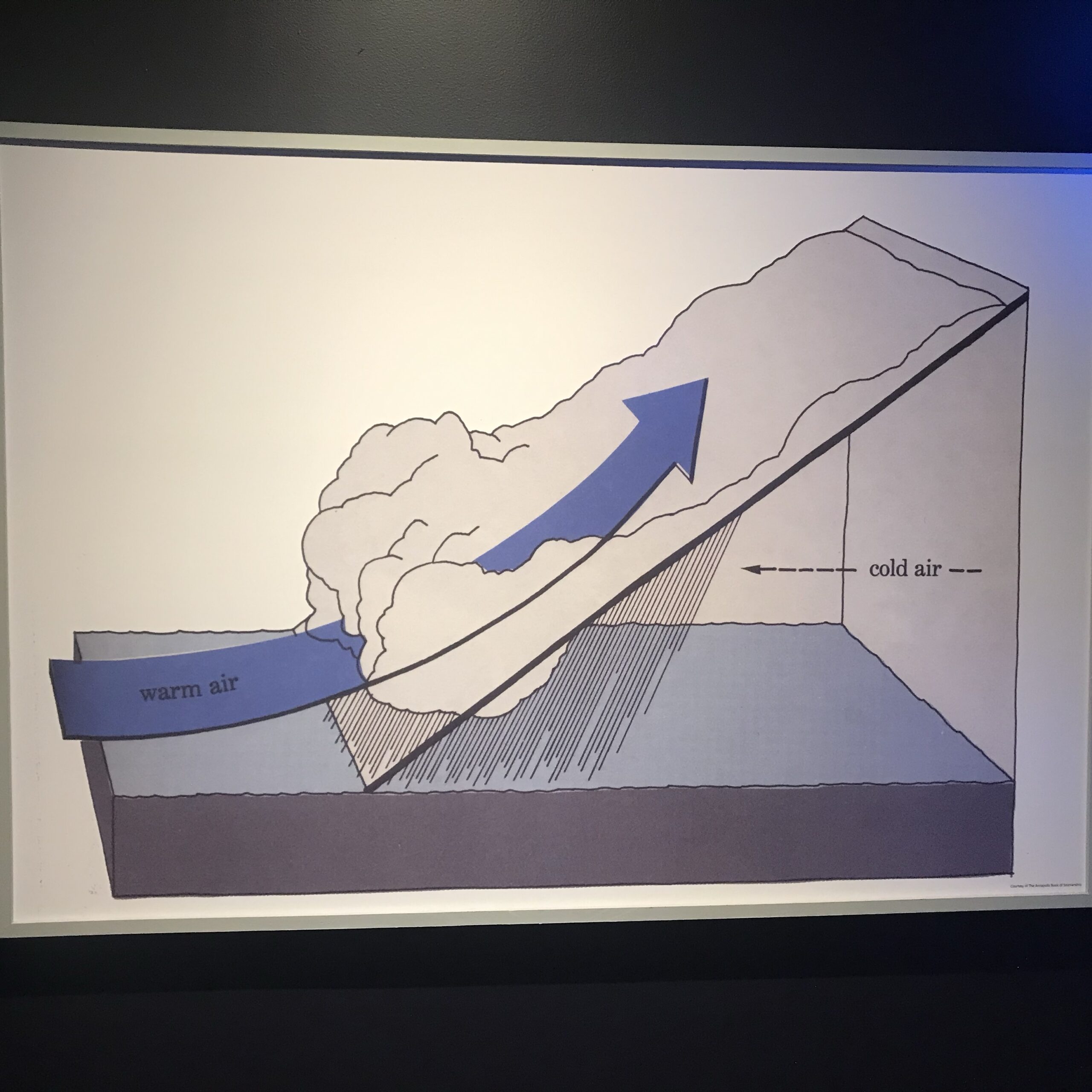

The Pacific Ocean is the largest water mass on the planet. It is larger than all of the earth’s land area combined. It contains almost twice as much water as the Atlantic Ocean.

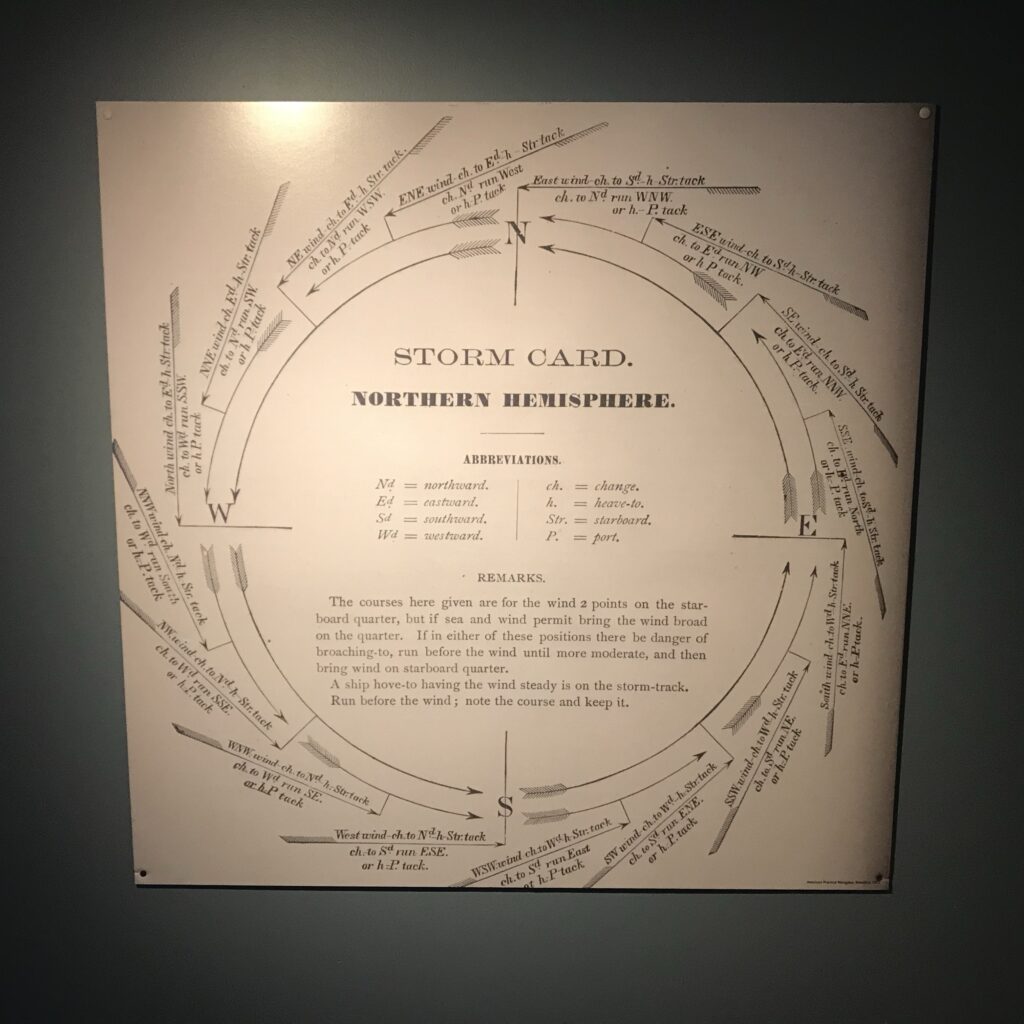

In the northern hemisphere the flow of the winds and ocean currents push a constant track of storms to the Pacific Northwest in the winter.

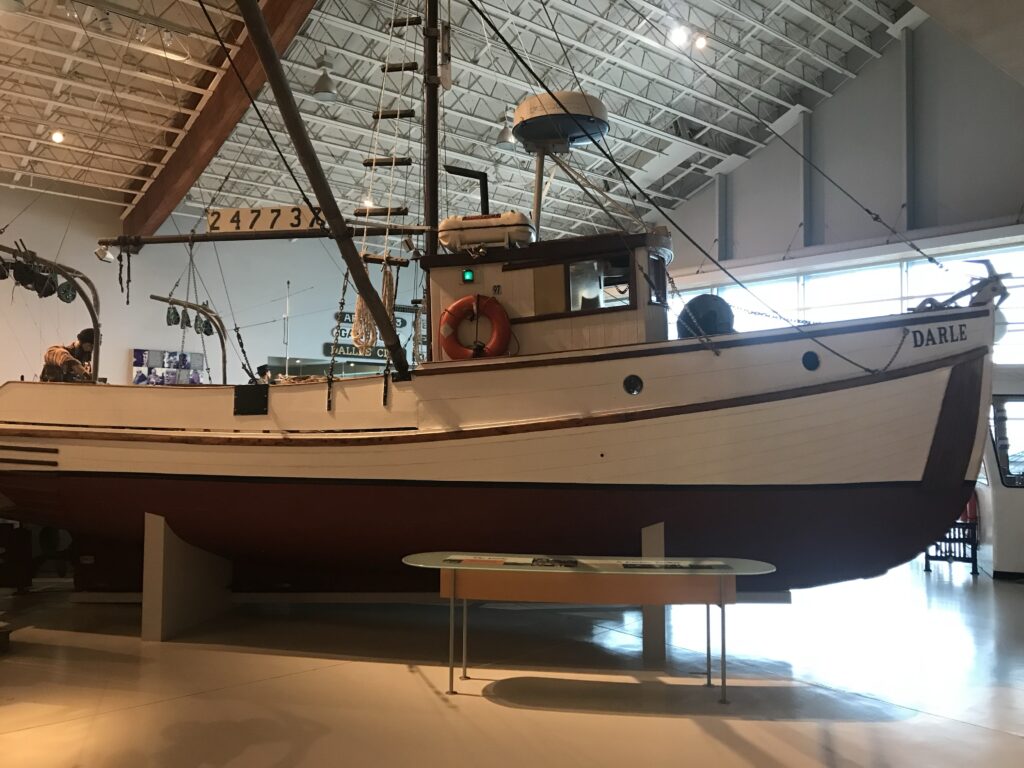

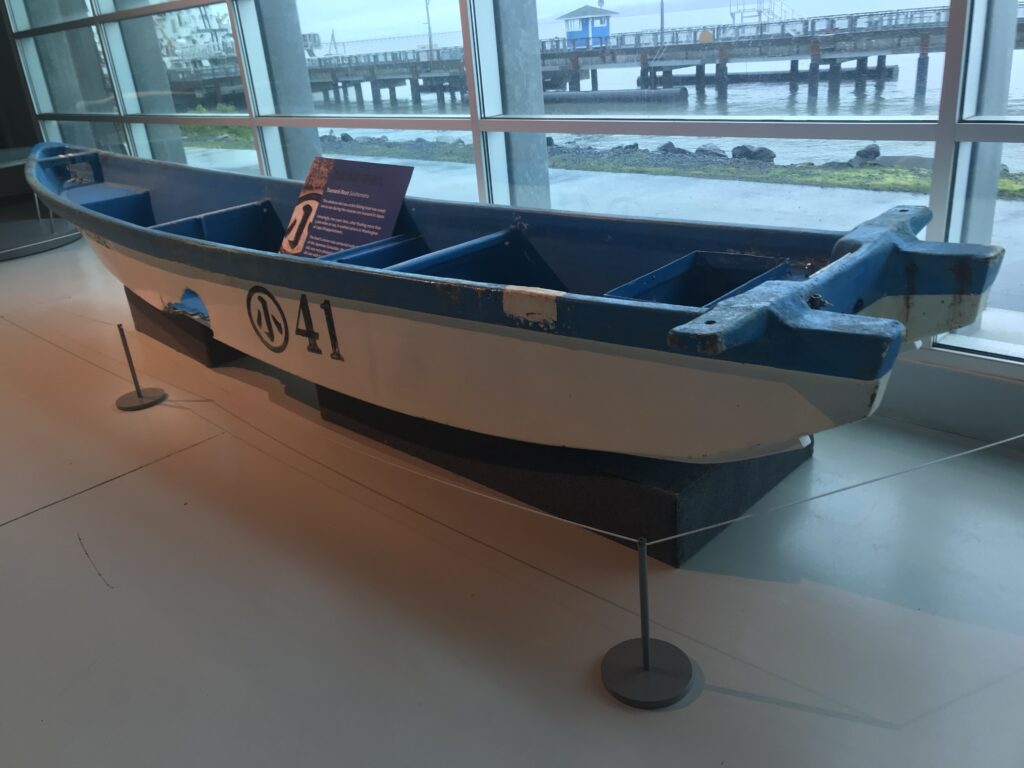

This abalone and sea urchin fishing boat was swept out to sea during the massive 2011 tsunami in Japan. Amazingly, two years later, after floating more than 5,000 miles at sea, it washed ashore in Washington at Cape Disappointment.

The boat’s owner was contacted with the assistance of the Japanese Consulate. Mr. Katuo Saito, 72 years old, was very pleased to hear his boat was found, but did not wish to have it returned to him. The Museum is honored to be able to display this boat and share its story.

- Beaufort number 3 is termed a “gentle breeze,” with wind between 7 and 10 knots (8–12 mph). The sea forms large wavelets, crests begin to break, and there might be scattered whitecaps; on land, leaves and twigs are in constant motion and light flags extend.

In 1775 the Spanish schooner Sonora sailed the Northwest coast on a scouting mission for the Spanish Empire. Small boats like this replica of Sonora’s launch were used for much of the early surveying and exploring in the Pacific Northwest.

- A Beaufort number of 4 is called a “moderate breeze,” measured at 11–16 knots (13–18 mph), producing small waves that become longer and frequent whitecaps. On land, it raises dust and small branches move easily.

- Number 5, “fresh breeze,” occurs at 17–21 knots (19–24 mph) and creates moderate waves and numerous whitecaps; small trees in leaf begin to sway and crested wavelets form on inland waters. A “strong breeze,”

- Beaufort 6, blows at 22–27 knots (25–31 mph), forming large waves and extensive foam crests at sea, with large branches in motion and umbrellas difficult to use on land.

Finally, despite its needed strength, a lifeboat must be relatively light and fast.

- The “moderate gale” or “near gale,” number 7, is defined by 28–33 knots (32–38 mph). Seas heap up and white foam from breaking waves is blown in streaks, while on land whole trees are in motion and it’s inconvenient to walk against the wind.

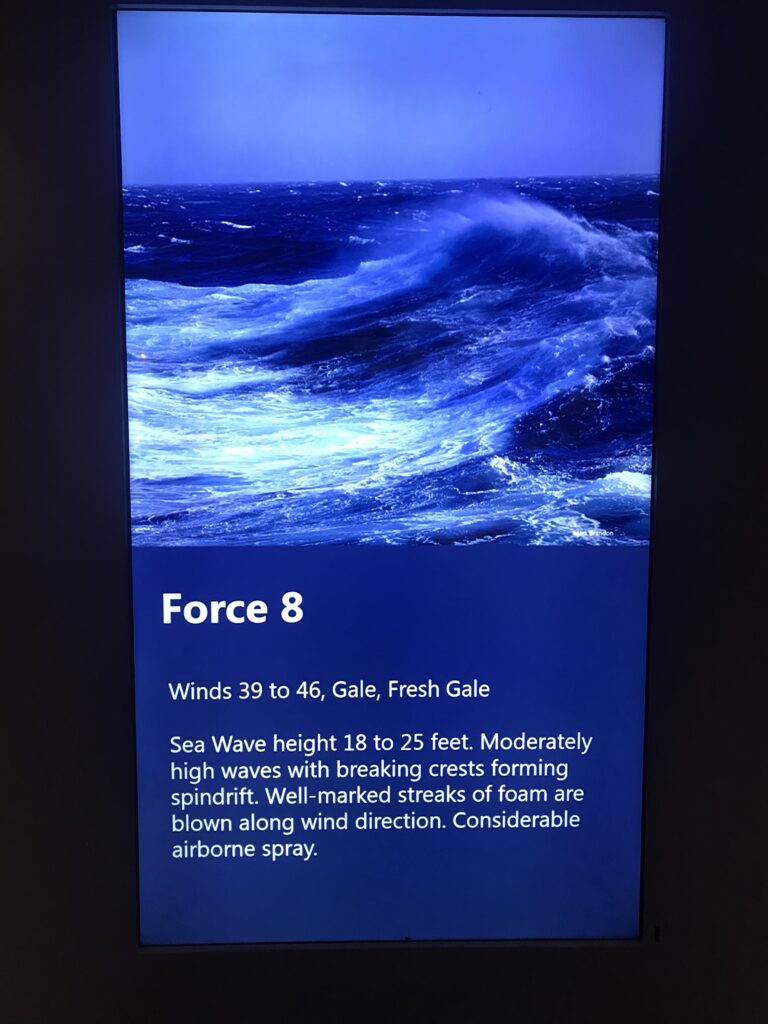

- An actual “gale,” number 8, with 34–40 knots (39–46 mph), brings high waves, breaking crests, and blowing foam; progress on land is impeded and twigs break from trees.

- Number 9, known as a “strong” or “severe gale,” comes with 41–47 knots (47–54 mph). The sea shows dense streaks of foam along the wind direction, waves can roll, and spray affects visibility; small structures can be damaged.

- Number 10, a “storm” or “whole gale,” with 48–55 knots (55–63 mph), features very high waves with long, overhanging crests, heavy rolling, and white-outs of sea and foam, while trees become uprooted and considerable structural damage occurs on land.

- At number 11, a “violent storm” blows at 56–63 knots (64–72 mph), bringing exceptionally high waves that can obscure ships, and widespread land damage rarely experienced inland.

- Beaufort number 12, or “hurricane”, is anything above 64 knots (≥73 mph). The air and sea fill with foam and spray, visibility is severely limited, and the word “devastation” best captures the consequences on land and sea alike.

Local Indians, whose lives depended on the Columbia River, were intimately familiar with its characteristics. They developed highly efficient craft, some as long as 50 feet, to negotiate the treacherous waters of the bar.

Ship Models and Descriptions

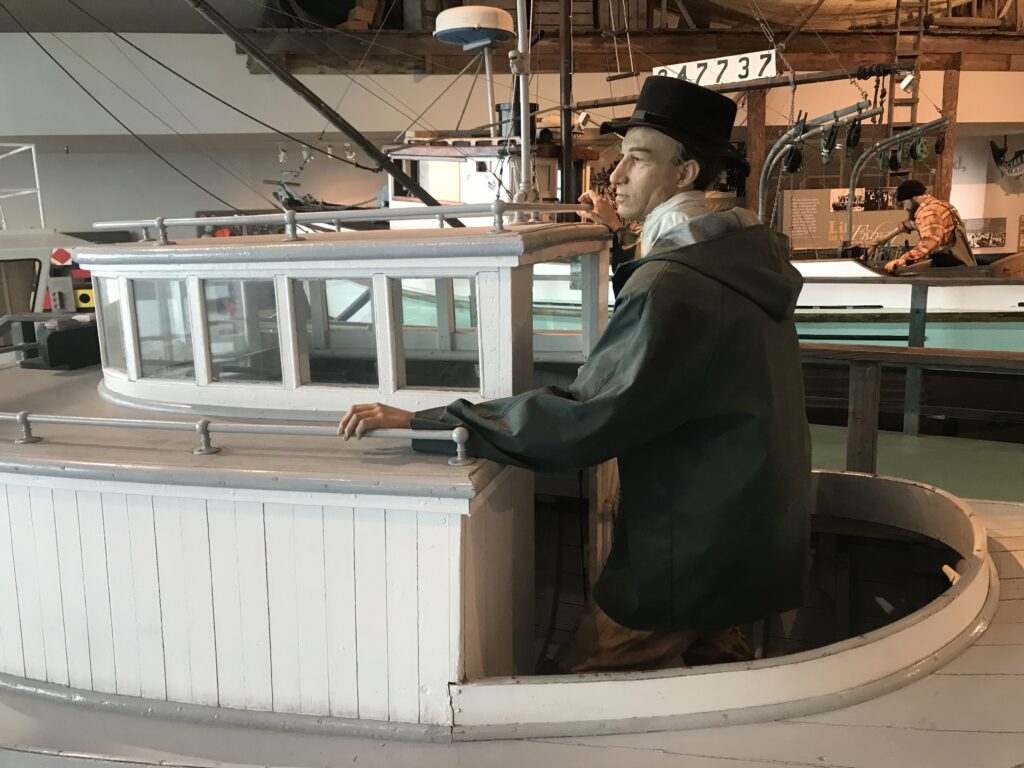

The upcoming Mariners Hall expansion will showcase a vastly increased number of model ships and real vessels. The collection historically features everything from dugout canoes to detailed models of famous local vessels, WWII ships, classic salmon trollers, and Coast Guard craft, each with interpretive descriptions on their design, history, and role in river and coastal life.traveloregon+1

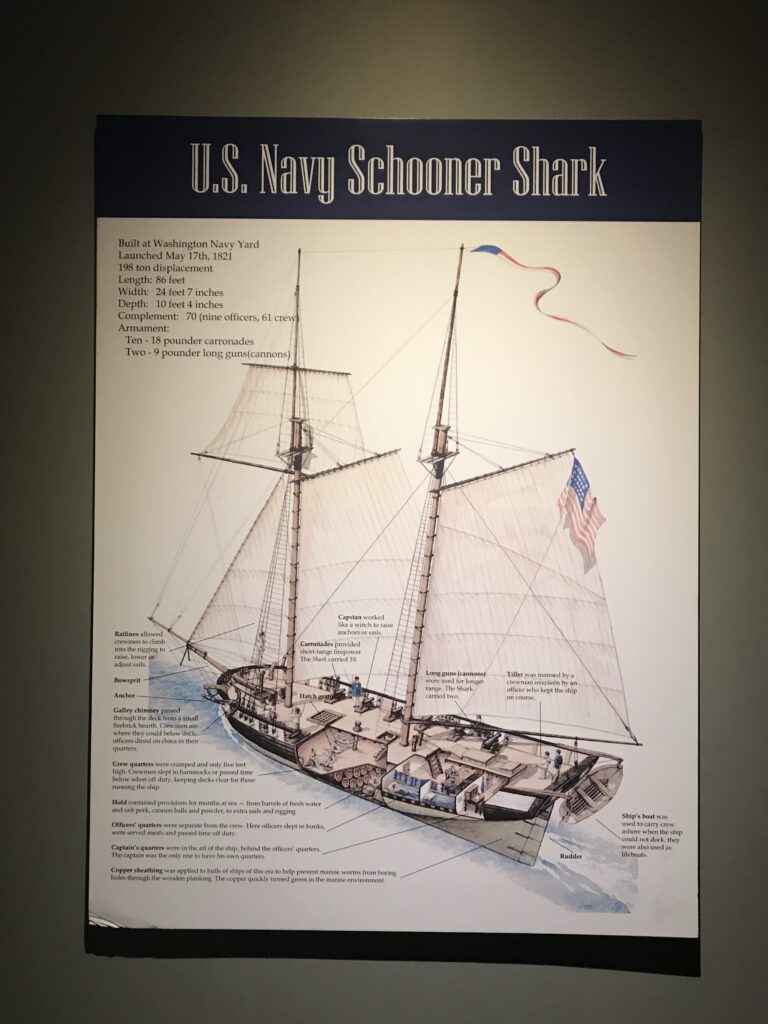

The Shark reached the coast of Oregon in July 1846 with orders to survey the Columbia River. In September, their mission complete, they attempted to leave the river.

However, the journey ended in disaster when the ship was swept into the breakers on the legendary Columbia River Bar.

Among model displays, you’ll find accurate reconstructions of the Columbia Rediviva (Gray’s ship), classic lightships, regional merchant and fishing vessels, and Coast Guard lifeboats.crmm+2

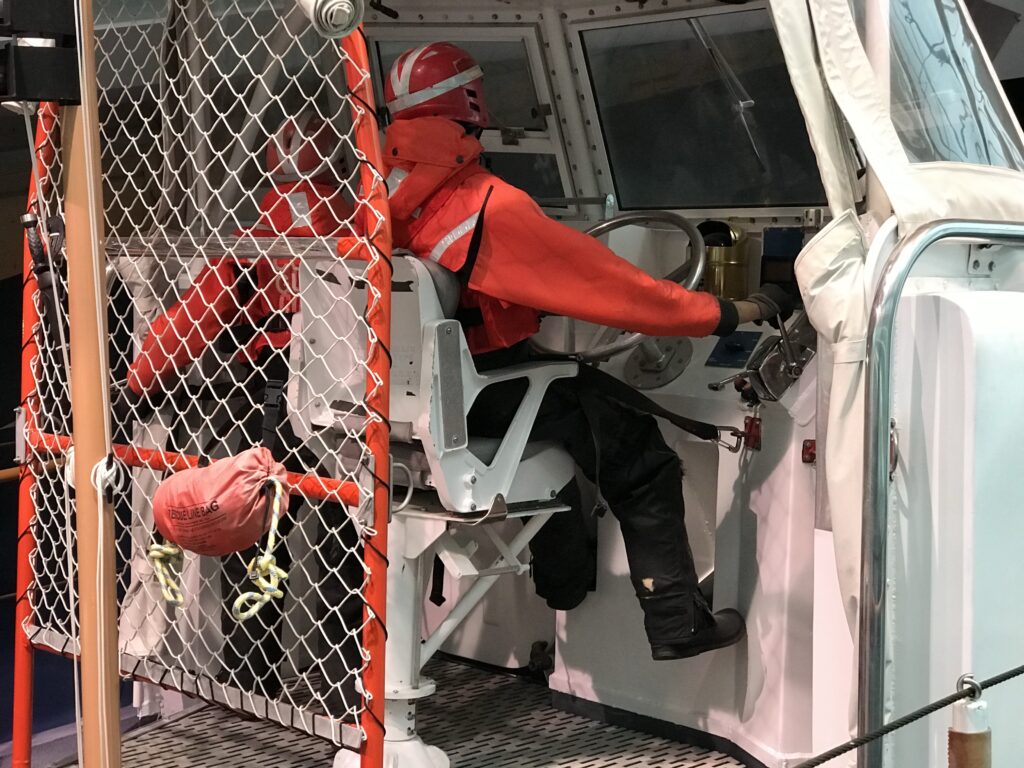

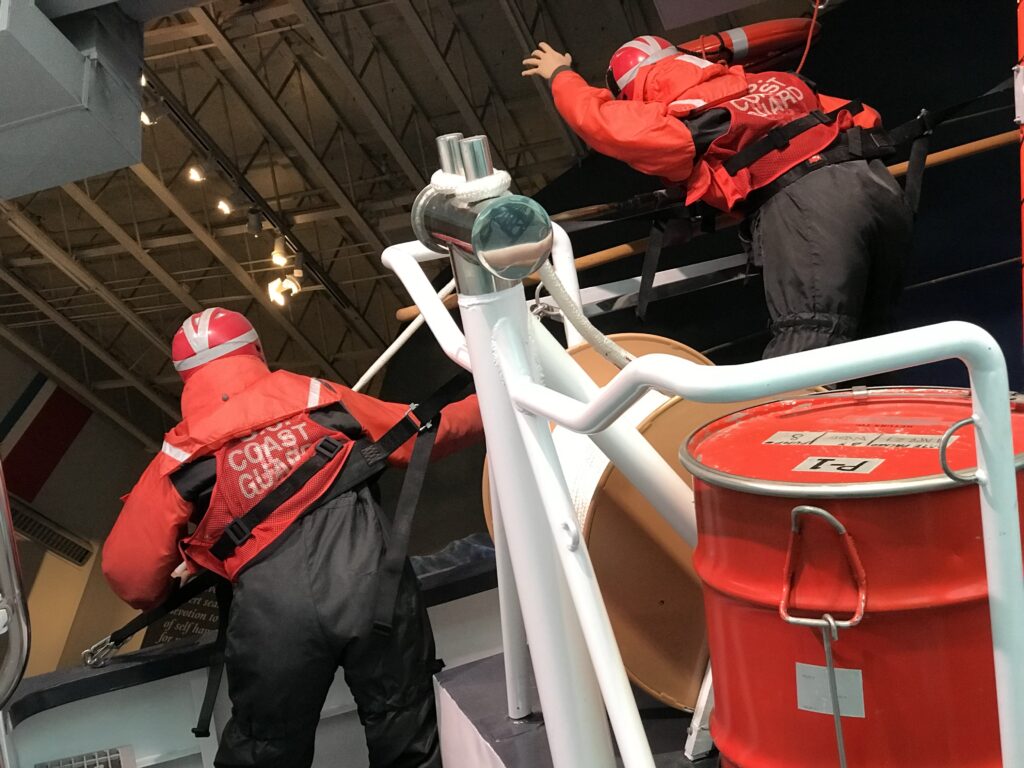

Actual Surf Boat Display

The museum has a life-size 44-foot Coast Guard surf rescue boat on static display, often modeled with lifelike dummies posed in dramatic rescue scenarios. The diorama captures the intensity of bar rescues, showing a crew in foul weather gear braving massive surf, illustrating not only technological evolution but the relentless courage of local mariners.traveloregon+1

Once the Mariners Hall expansion is complete, this lifeboat will be joined by others like the 52′ TRIUMPH, offering additional context and more elaborate rescue scene recreations.facebook+1

Visiting Experience

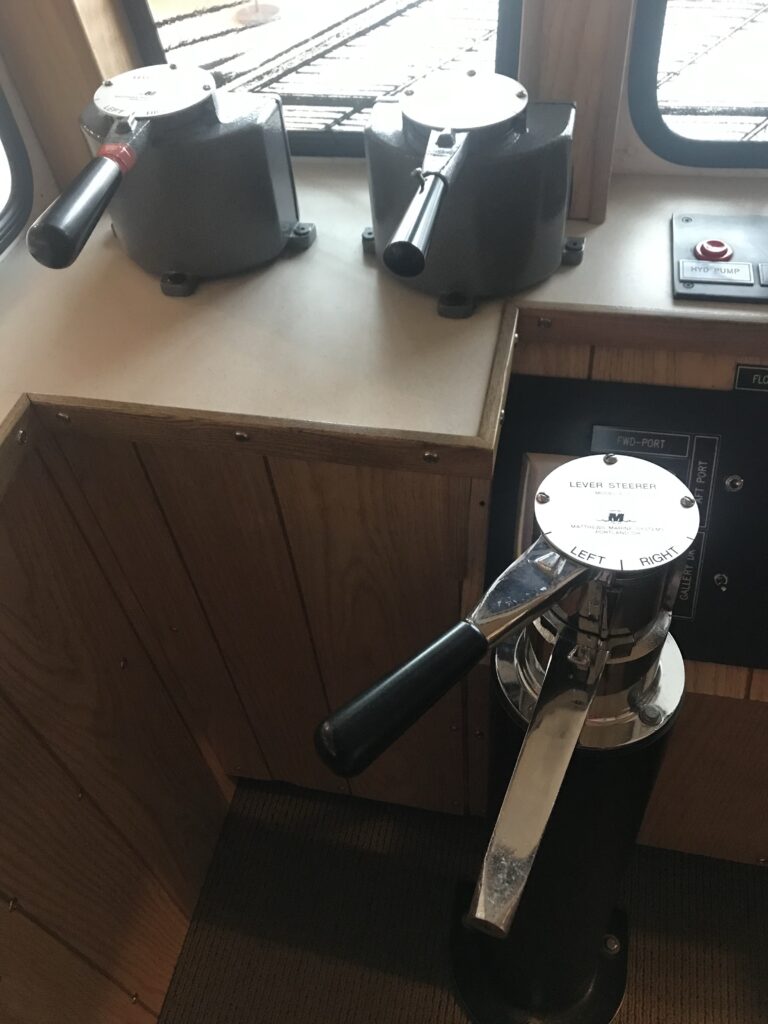

- Besides historic vessels, visitors can interact with ship simulators (like tugboat steering), pilot virtual rescues, watch an orientation film, and stroll among artifacts with tactile and visual displays—making the museum appealing to anyone interested in hands-on and family-friendly experiences.traveloregon+1

In summary, the Columbia River Maritime Museum is central to an Astoria visit for its immersive, expertly curated interpretation of Pacific Northwest maritime history, uniquely blending real vessels, detailed models, and lifelike rescue dioramas to tell the compelling story of the river, sea, and those who navigated them.crmm+3

“there is one difficulty that will ever exist in passing over the bar, and this, nothing but an intimate acquaintance with the locality will remove. I allude to the cross-tides, which are changing every half-hour. These tides are at times so rapid, that it is impossible to steer a ship by her compass, or maintain her position… the safest time to cross the bar is when both tide and wind are adverse; and this is the only port, within my knowledge, where this is the case.”

Bar Wrecks

1. Schooner Americana

Carrying a load of lumber bound for Sydney, Australia, she disappeared on February 28, 1918, soon after crossing the bar. No trace of the ship or her eleven crewmen was ever found.

2. Tuna seiner Bettie M.

The ship ran aground on the sandy shoals of the bar near Jetty A on March 20, 1976.

The crew of ten was safely evacuated by a Coast Guard helicopter, but the boat and her catch, 900 tons of tuna, were a total loss.

3. Schooner Champion

She was outward-bound from the Columbia on April 15, 1870, when the wind died and currents swept her onto the north spit. Two drowned trying to escape the wreck. A third crewman washed ashore the next day lashed to an overturned lifeboat, barely alive.

4. Freighter Laurel Outbound with a cargo of 7 million feet of lumber, Laurel was swept onto Peacock Spit on June 16, 1929. Initial Coast Guard rescue attempts were foiled by spilled lumber. When the ship broke in two, a 19-year old seaman drowned; the rest of the crew was eventually rescued. The ship’s captain refused to abandon ship, remaining on board for 54 hours.

5. Fishing boat Electra

She was stranded inside the bar on Clatsop Spit on January 26, 1944. The crew was rescued, but several attempts by the Coast Guard to pull her off the spit were unsuccessful. One year later her mast could still be seen sticking out of the sand.

6. Steamship Francis H. Leggett

The Leggett was steaming past the Columbia River on her way to San Francisco with a cargo of railroad ties on September 18, 1914. A tremendous gale struck, and she went down 60 miles southwest of the river’s mouth with a loss of sixty-five lives.

7. steamer Generat varren

When she started foundering in a gale, Captain Thompson decided there would be more chance of survival if the ship was beached. Run aground at Clatsop Spit on January 18, 1852, the ship was pounded to pieces by the surf and forty-two lives were lost.

8. Bark Harvest Home

Sailing to Port Townsend in a blanketing fog, Harvest Harveck Home ran aground on North Beach Peninsula, just a few hundred feet from a farm, on January 18, 1882. A defective chronometer had led the captain to set the wrong course. The crew walked ashore, and the unsalvageable vessel was abandoned.

9. Sidewheel Steamer Great Republic

With more than 1000 people on board, the Great Republic ran aground on Sand Island in the early morning of April 18, 1879. Throughout the next day, passengers were evacuated as the ship slowly broke apart. Eleven crew members drowned during the evacuation.

10. Freighter Baby Doll, 1955; crew saved.

11. British bark Cape Wrath, 1901; 15 lost.

13. Schooner Carrie B. Lake, 1886; 3 lost.

14. American freighter Permanente Cement, 1954; crew saved.

15. Bark Desdemona, 1857; 1 lost.

16. Fishing vessel Elsie Faye, 1960; crew survived.

17. Steam tug Firely, 1854; 4 lost.

18. Fishing vessel Flora, 1954; 2 lost.

19. Tug Governor Moody, 1952; crew waded ashore.

20. Brig Hazard, 1798; 5 lost, the ship survived.

21. Fish packer Ida Mae, 1953; crew swam to safety.

22. Bark Industry, 1865; 17 lost.

23. Pilot schooner J.C. Cousins, 1883; 4 lost.

24. Fishing vessel Jennie F. Decker, 1981; crew rescued.

25. Steamship Mauna Ala, 1941; crew saved.

26. Trawler LaBelle, 1945; 1 lost.

27. Fishing boat Mary Joanne, 1969; crew rescued by pilot boat.

28. Motor craft Mizpah, 1952; 2 lost.

29. Fishing boat Nemanshoa, 1925; 2 lost.

30. Diesel tug Neptune, 1948; 1 lost.

31. U.S. Navy minesweeper Nightingale, 1941; crew rescued.

32. Luxury yacht Nuny II, 1967; 3 lost.

33. U.S. Navy brig Peacock, 1841; no loss of life.

34. Motor schooner Pescawha, 1933; 1 lost.

35. Schooner Rambler, 1860; 4 lost.

36. Tanker Rosecrans, 1913; 33 lost.

37. British bark Lupatia, 1881; 16 lost.

38. Fishing vessel Six-Pack, 1985; 1 lost, 2 rescued.

39 Bark Vandalia, 1853; 9 lost.

40 Barkentine Web Foot, 1904; crew reached shore safely.

41. British steamship Welsh Prince, 1922; 7 lost.

42. Bark Whistler, 1883; crew saved.

42. Fishing vessel Rose Ann, 1948;

4 lost.

43. British brig William and Ann, 1829; estimated 46 lost.

48. Charter fishing vessel Pearl C.

On the afternoon of September 13, 1976, the Coast Guard received a distress call from Pearl C. They took the leaking vessel in tow, but she heeled over and began sinking quickly. Two of the crew were rescued, but eight were never found, including the vessel’s captain.

49. Freighter Iowa

Crossing the bar January 12, 1936, in a gale estimated at 76 miles per hour, the lowa put out an SOS message. This brought the Coast Guard Cutter Onondaga to Peacock Spit, where the freighter had wrecked. Rescuers found only the masts and samson posts.

All 34 crew members perished.

50. Fishing boat Treo

On December 2, 1940, while the Treo was returning from a fishing trip, disaster struck. “We were hit by a big sea and she opened up and sank in about an hour … John Lampi’s boat Washington picked us up not a moment too soon.”

—Captain George Moskavita