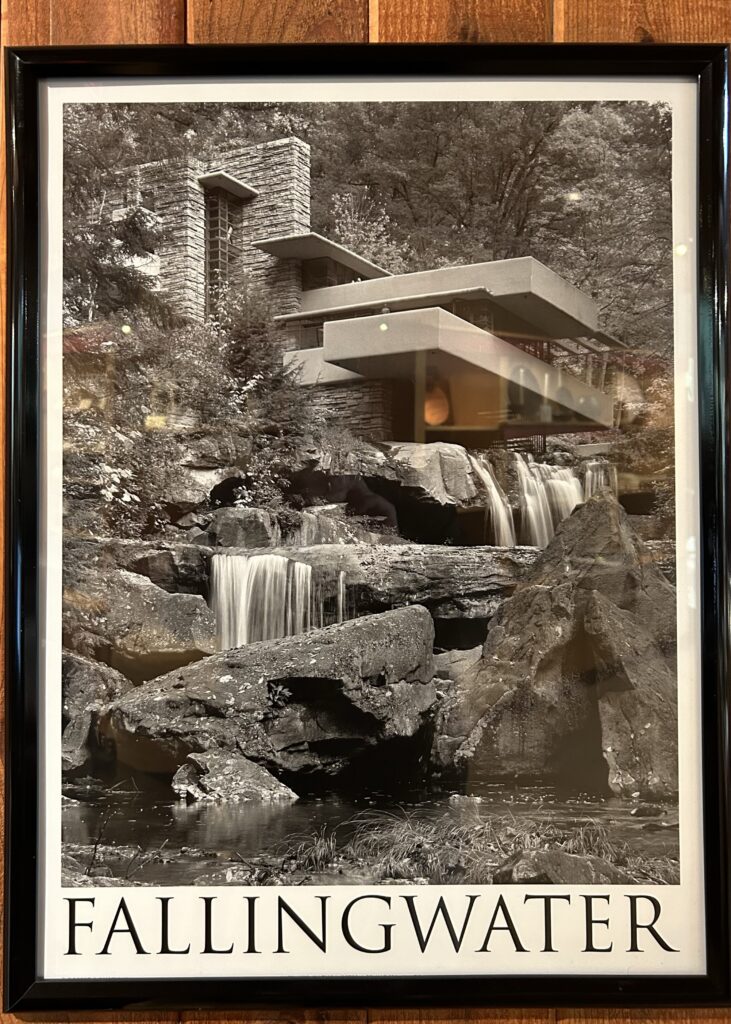

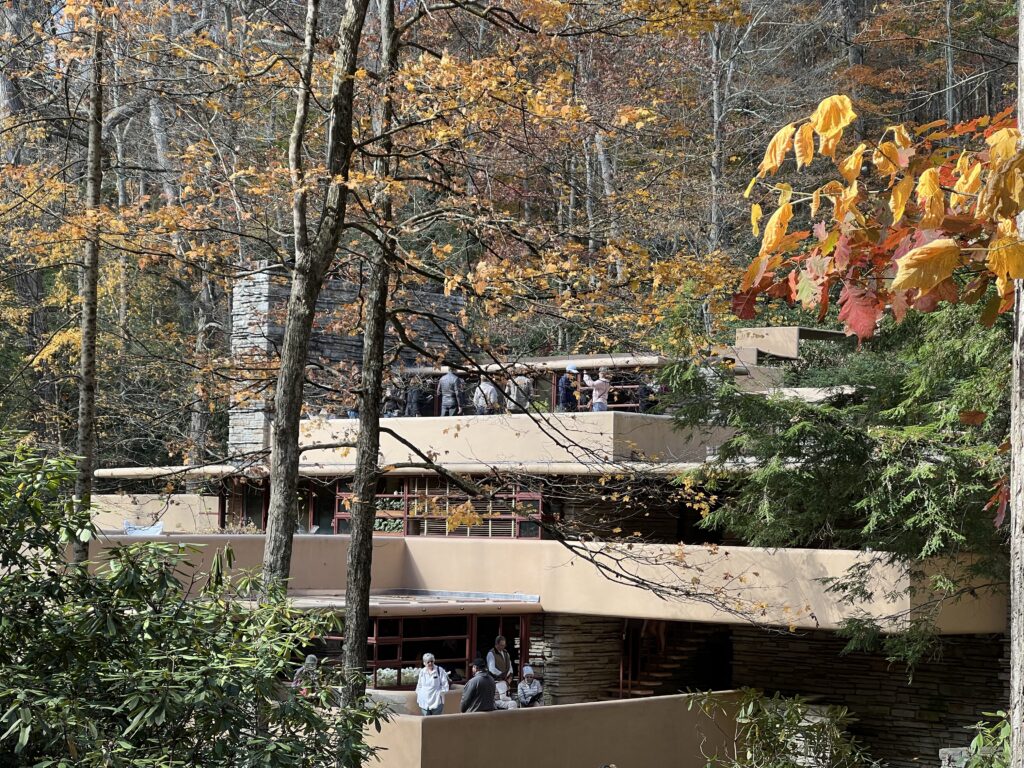

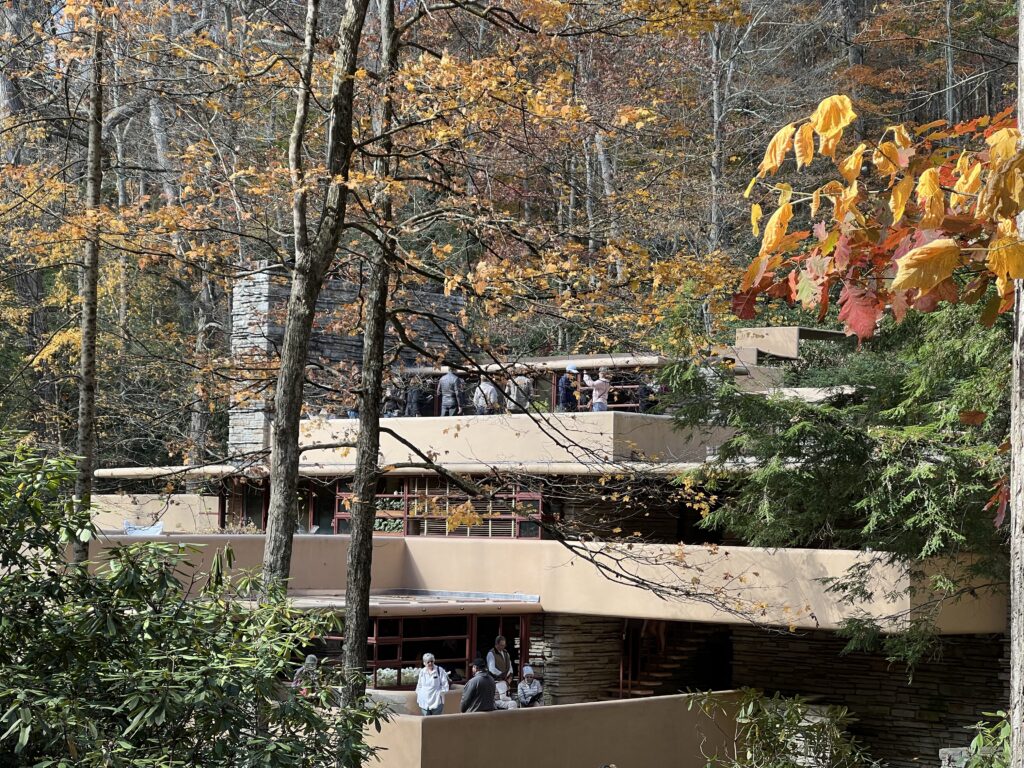

Fallingwater, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright and located in Pennsylvania, is of significant interest to both architects and historians due to its innovative design and historical importance.

Interest for Architects

- Organic Architecture: Fallingwater is a prime example of Wright’s concept of organic architecture, where the design harmoniously integrates with the natural surroundings. The house is built directly over a waterfall, which not only serves as a visual centerpiece but also fills the home with the sound of flowing water, embodying Wright’s philosophy of blending architecture with nature134.

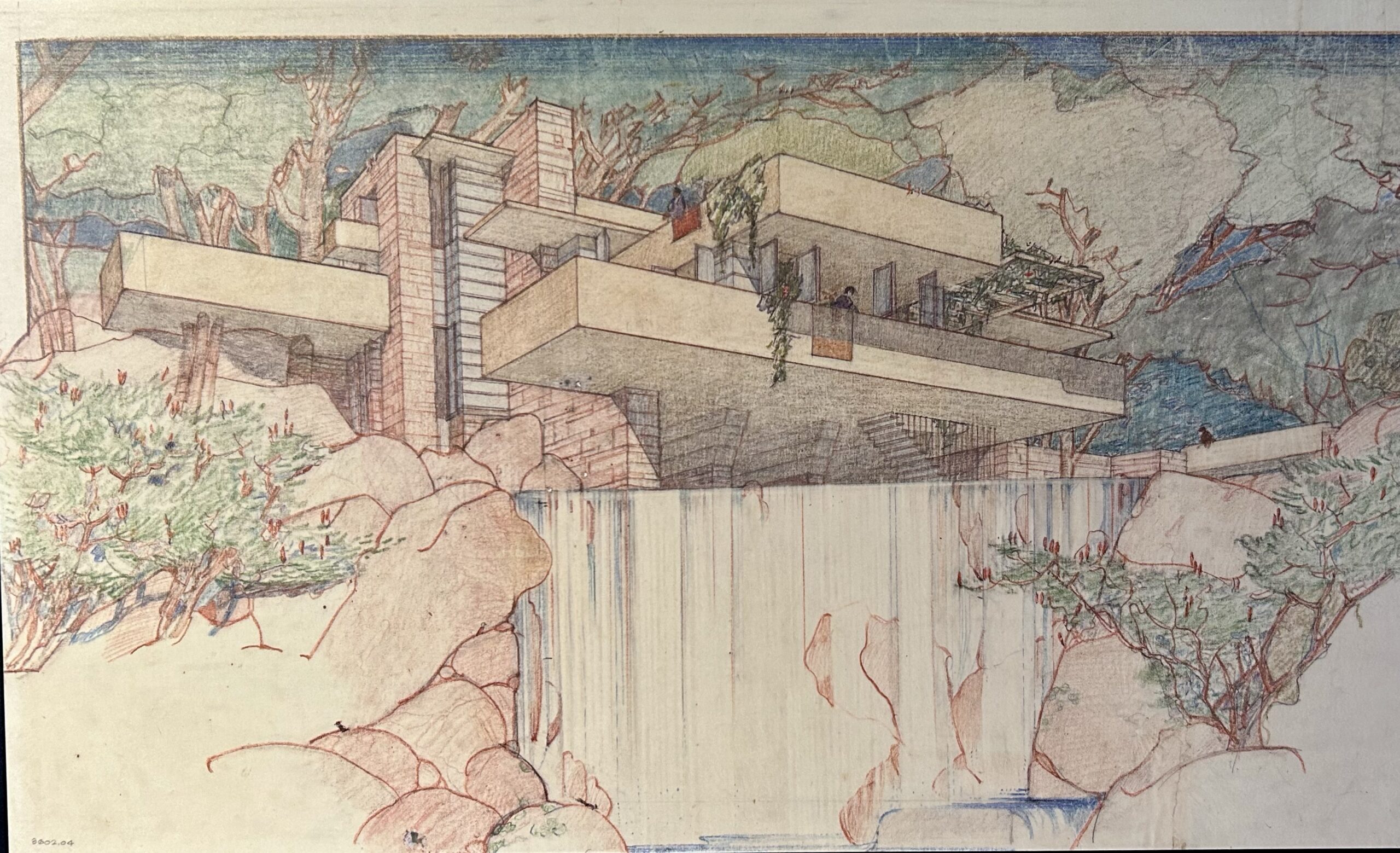

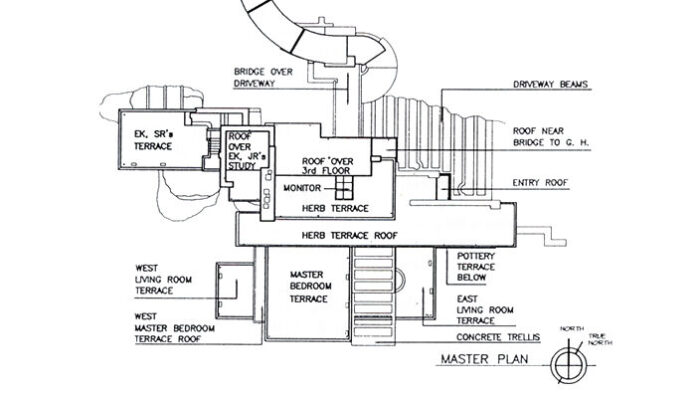

- Innovative Design and Construction: The house features cantilevered terraces made of reinforced concrete that appear to float above the waterfall. This design choice was groundbreaking at the time and showcased Wright’s ability to merge modern architectural techniques with natural landscapes24.

- Site Planning: Wright’s decision to place the house above the waterfall rather than beside it was a bold move that emphasized auditory experience over visual, challenging conventional architectural practices2.

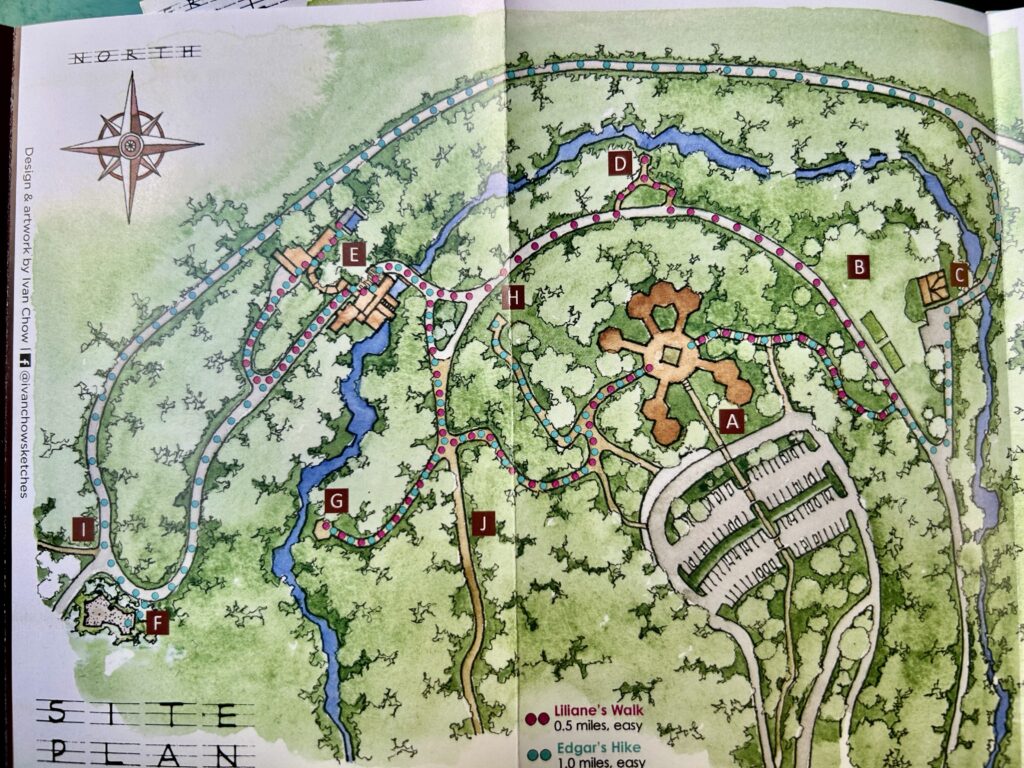

One of the most important residential designs of the twentieth century, Fallingwater was conceived as a country house for department store owner Edgar J, Kaufmann and his family. In 1916, Kaufmann began leasing the former Syria Country Club, established by Pittsburgh area Masons seven years earlier, as a weekend escape for the employees of their department store.

The camp was a collection of buildings and camp facilities, including a club house, a dozen or more cabins, tennis courts, a swimming pool, and trout hatchery. The Kaufmans erected their own cabin at Bear Run in 1921, ordering a prefabricated Genesee model from the Aladdin Company. Situated on a rock ledge overlooking Bear Run, the Kaufmanns nicknamed their getaway “The Hangover,” In 1927, Kaufmann’s Department Store purchased the camp but stopped using it as a company retreat around 1930, setting the stage for privaté use of the land by the Kaufmann family:

Frank Lloyd Wright visited the site in December 1934 while in Pittsburgh to discuss the design of an office for Kaufmann, a project that was completed in 1937. Positioned over Bear Run, Wright designed Fallingwater to project outward from nearby stone outcroppings while raising it upward on reinforced concrete bolsters that extended it over the falls, providing dramatic views from the house’s terraces.

In 1938, Wright was featured on the cover of Time with a rendering of Fallingwater behind him, and the Museum of Modern Art launched an exhibition on the house-its first exhibition dedicated to a single building. Edgar Kaufmann jr. donated Fallingwater to the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy In 1963, and a year later it began offering public tours.

“Fallingwater,” House for Mr. & Mrs. E. J. Kaufmann (1936) sign at site.

Interest for Historians

- Cultural and Historical Significance: Fallingwater is considered one of the greatest masterpieces of 20th-century architecture. It marked a pivotal moment in Wright’s career, reviving his prominence in the architectural world during the Great Depression45.

- Preservation and Legacy: The house has been preserved as a museum since 1964, maintaining its original furniture and art collection. It was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1976 and later became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2019, highlighting its enduring historical and cultural value45.

- Influence on Modern Architecture: Fallingwater has inspired architects worldwide and is often cited as a seminal work that influenced modern architectural movements. Its design principles continue to be studied and admired for their innovative approach to integrating human habitation with natural environments25.

For both architects and historians, Fallingwater represents a unique convergence of architectural innovation and historical significance, making it an enduring subject of study and admiration.

Fallingwater stands out among architectural works due to several unique design elements that showcase Frank Lloyd Wright’s innovative approach and philosophy of organic architecture.

Unique Design Elements

Cantilevered Terraces: One of the most striking features of Fallingwater is its cantilevered terraces, which extend dramatically over the waterfall (see above). These terraces create the illusion of floating above the falls and are anchored to a central stone chimney, demonstrating Wright’s mastery of balance and structural innovation124.

Integration with Nature: Wright’s design philosophy emphasized harmony between architecture and nature. Fallingwater exemplifies this by being built directly over a waterfall, allowing the sound and presence of water to permeate the house. The use of local materials, such as sandstone quarried nearby, and the ochre color of the concrete help the house blend seamlessly into its natural surroundings235.

Organic Architecture: Wright’s concept of organic architecture is evident in how Fallingwater grows from its rocky landscape. The house is designed to appear as if it emerges naturally from the ground, with stone piers resembling the natural rock strata and reinforced concrete slabs that mimic the flow of the stream below13.

Geometric Harmony: The design incorporates subtle geometric regulations, such as a 30-60-90 triangle that organizes the building’s layout. This geometric precision contributes to the building’s aesthetic balance and harmony1.

Frank Lloyd Wright was approximately 5 feet 8 inches tall3 and it is often said that he designed structures to his personal height which he believed was the height proscribed by the classic architect Vitruvian. However, Wright’s understanding of human scale, while including his notion of the “Vitruvian Man” went beyond this, advocating for spaces that felt comfortable and human-scaled.

Vitruvius, the architect, says in his architectural work that the measurements of man are in nature distributed in this manner, that is 4 fingers make a palm, 4 palms make a foot, 6 palms make a cubit, 4 cubits make a man, 4 cubits make a footstep, 24 palms make a man and these measures are in his buildings. If you open your legs enough that your head is lowered by 1/14 of your height and raise your arms enough that your extended fingers touch the line of the top of your head, let you know that the center of the ends of the open limbs will be the navel, and the space between the legs will be an equilateral triangle[13]

Wright’s design philosophy often involved lower ceiling heights, influenced by his understanding of human scale rather than the Vitruvian Man specifically. He believed that some spaces should be intimate, with lower ceilings in areas for sitting and higher ceilings in areas for standing or moving12.

Modern building codes in the U.S. typically require a minimum ceiling height of 7 feet for habitable spaces4. The average ceiling height in new homes today is around 9 feet4. The average height of a U.S. resident is approximately 5 feet 9 inches for men and 5 feet 4 inches for women.

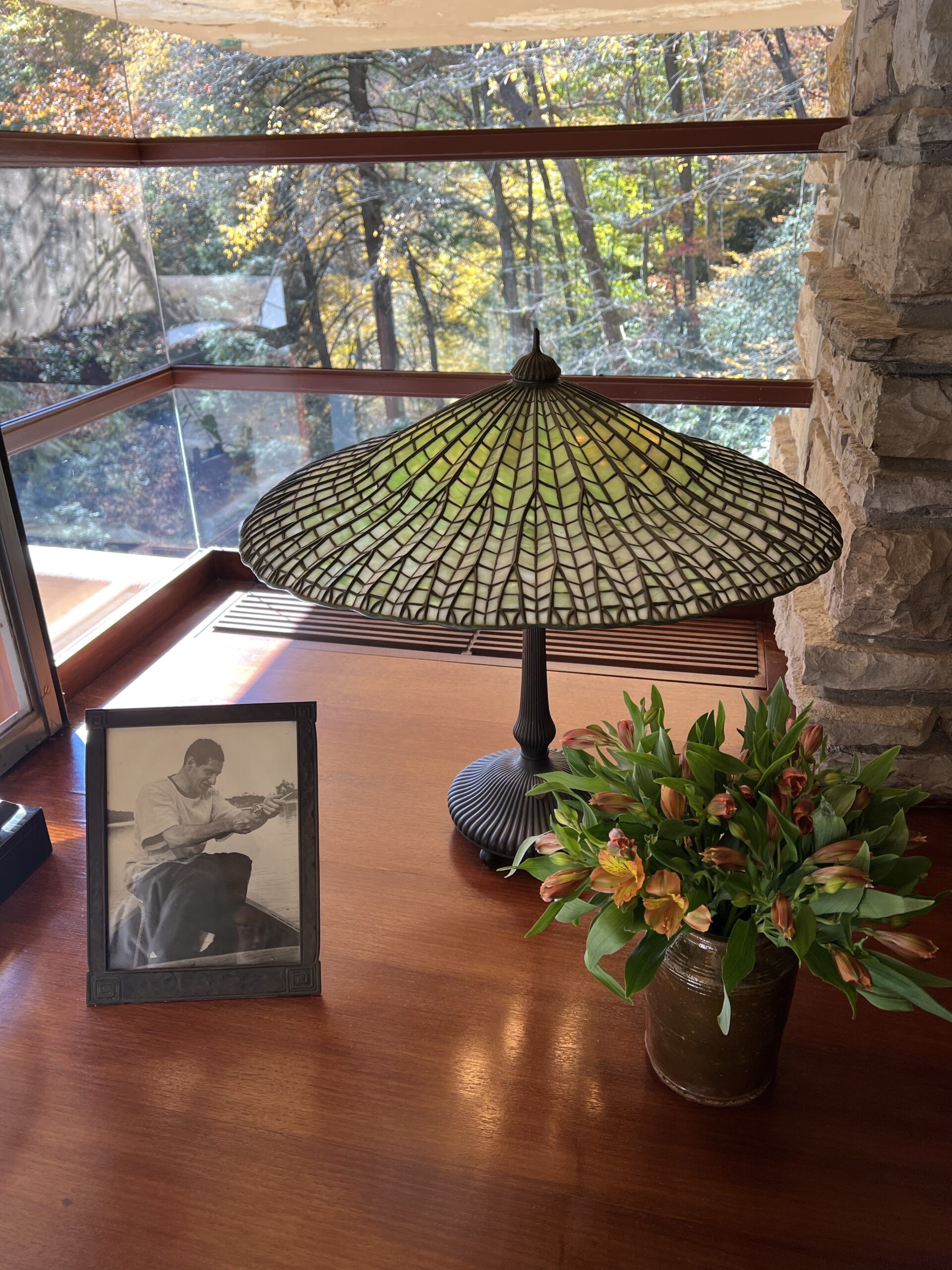

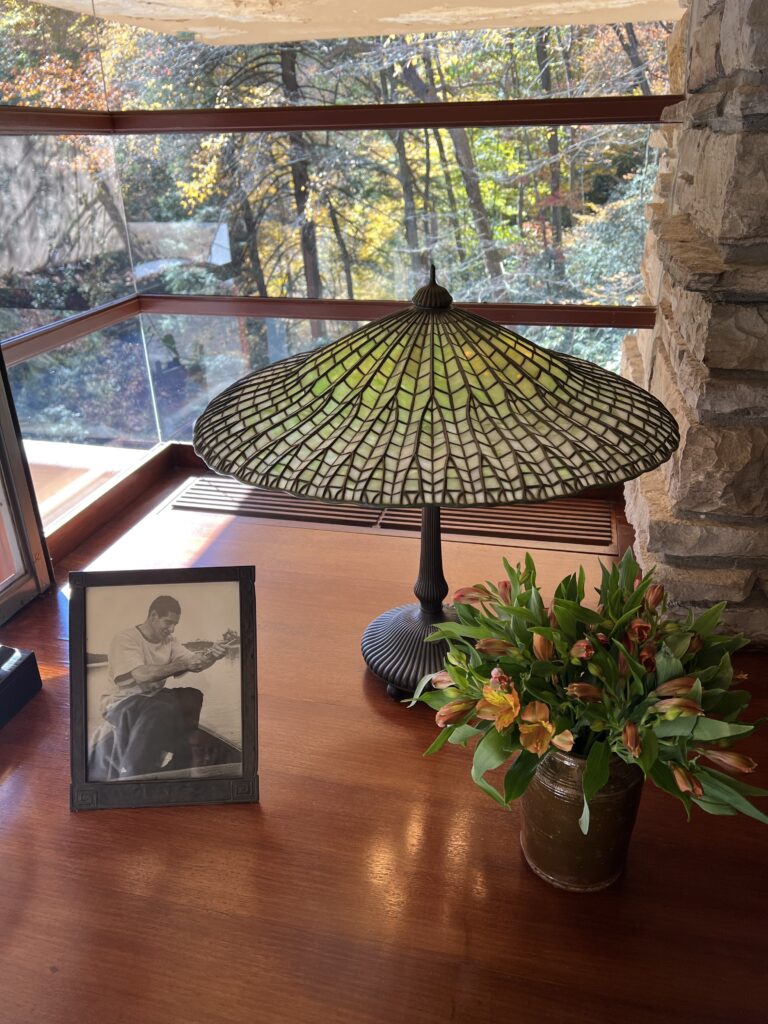

Interior-Exterior Connection: Wright designed Fallingwater to blur the lines between indoor and outdoor spaces. Large windows and glass doors open up to expansive terraces, allowing natural light to flood the interiors and providing unobstructed views of the surrounding landscape. This connection is further enhanced by features like a hatch leading directly from the living room to the stream below234.

Central Fireplace: The fireplace serves as a focal point in Fallingwater, embodying Wright’s belief in its importance as a gathering place. A natural boulder forms part of the hearth, physically bringing elements of the site into the home45.

Compression and Release Design: This is an architectural concept that involves creating a sequence of spaces that transition from narrow, confined areas to larger, open ones. This dynamic interplay generates a sense of movement and emotional response, enhancing the overall experience of the space. The concept is likened to a cave because, much like moving through a cave, one experiences moments of constriction followed by expansion. This creates a journey-like experience where the initial compression evokes feelings of containment, which are then released into openness and freedom, similar to emerging into a larger cavern after navigating through narrow passages.

Ship Grade

Recognizing the challenges of building in a wet location, ship grade or marine-grade plywood was used at Fallingwater, but it was veneered with North Carolina black walnut. Here are the key points:

- The furniture at Fallingwater was constructed using plywood for versatility in design and resistance to warping. This plywood was then veneered with North Carolina black walnut.

- Specifically, the built-in wardrobes were made of marine-grade plywood veneered with North Carolina black walnut.

- All of the woodwork at Fallingwater used marine-grade plywood, which was chosen because it’s resistant to warping in humid environments. This plywood was then veneered with North Carolina black walnut.

- The plywood was cut and milled by the Gillen Company in Milwaukee, which was the successor to the defunct Matthews Brothers Company that Wright had used for his Prairie style houses.

- The “ship-grade” designation indicates its suitability for demanding environments, ensuring durability and longevity in marine settings. The clients owned a desert house in Palm Springs, California, designed by Richard Neutra. and Write was concerned that his clients would introduce furniture unsuitable for a structure over a waterfall and tried to “client proof” fallingwaters by building the furniture directly into the structure.

These elements collectively make Fallingwater not only an architectural masterpiece but also a profound example of how buildings can coexist with their natural environments.

Uneven floors made four legged chairs wobbly and the clients replaced most of the Frank Lloyd Wright designed chairs with three legged chairs.

Use of Materials Reflecting Honesty

The use of materials in Fallingwater reflects Frank Lloyd Wright’s principles of honesty in several key ways, emphasizing the natural beauty and inherent qualities of the materials themselves.

Local Sandstone: Wright used locally sourced sandstone for the construction of Fallingwater, which allowed the house to blend seamlessly with its natural surroundings. This choice of material reflects Wright’s principle of honesty by using materials that are true to the site and environment, creating a sense of unity between the building and its natural setting12.

Reinforced Concrete: The use of reinforced concrete for the cantilevered terraces was a bold and innovative choice. Wright embraced the material’s structural capabilities, allowing for expansive overhangs that appear to float above the waterfall. This use of concrete demonstrates honesty by showcasing the material’s strength and flexibility without unnecessary ornamentation, highlighting its functional role in the design4.

Natural Integration: Wright incorporated natural elements directly into the architecture, such as a fountain that diverted a spring. This integration emphasizes the authenticity and honesty of using materials in their natural state, rather than altering them to fit a preconceived aesthetic13.

Minimal Color Palette: The exterior color palette was kept minimal, with light ochre concrete and red steel frames that complement the surrounding landscape. This restrained use of color reflects an honest approach by allowing the materials’ natural colors to enhance the building’s connection to its environment1.

Use of Glass: The use of glass was integral to Frank Lloyd Wright’s design philosophy, emphasizing transparency and the integration of indoor and outdoor spaces. Large expanses of glass were used to create uninterrupted views of the surrounding landscape, enhancing the organic architecture of the house.

The architectural term for windows where glass meets at corners is typically referred to as “glass-to-glass corner windows” or “frameless corner windows.” These windows are characterized by two panes of glass that meet at a corner without a visible frame or mullion between them. Here are some key points about this type of window:

- Definition: Glass-to-glass corner windows are when two panes of glass meet at a corner, connected using structural silicone to create a weatherproof seal and a neat appearance2.

- Design: These windows have no frame between the glass panes, ensuring uninterrupted views and allowing maximum light into the room2.

- Architectural trend: Frameless corner windows are a fast-growing trend in architectural glazing, valued for their minimalist aesthetic and ability to create panoramic views2.

- Versatility: They can be integrated with other glazing systems such as fixed windows, opening windows, sliding doors, or bi-folding doors2.

- Structural considerations: Corner windows require careful planning from an early design stage due to structural implications. The corner of the room must support the ceiling or roof above without needing brickwork or a corner post2.

- Installation: These windows are typically installed where views can be enjoyed the most, creating a focal point and a “wow factor” for a room2.

- Architectural applications: While they can fit into various architectural styles, frameless corner windows are particularly effective for joining old and new design elements2.

It’s worth noting that while “glass-to-glass corner window” is the most precise term, architects and designers might also use variations like “corner glazing,” “frameless corner glazing,” or simply “corner windows” when referring to this design feature.

The Hope Glass Company of Jamestown New York provided the high-quality glass that met Wright’s design specifications for this iconic project. The company still has a dedicated testing and R&D facility in Jamestown.

“Handcrafting the World’s Finest Solid Steel and Bronze Windows and Doors for Over a Century

Through these choices, Wright adhered to his philosophy of organic architecture, where materials are used in a way that respects their natural properties and enhances the overall harmony between the building and its environment.

Historical Events

Fallingwater is associated with several significant historical events that highlight its architectural, cultural, and historical importance.

Design and Construction (1935-1937): Fallingwater was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1935 for the Kaufmann family, owners of a Pittsburgh department store. The construction began in 1936 and was completed in 1937. This period marked a turning point in Wright’s career, as the project revived his reputation as a leading architect during the Great Depression24.

Time Magazine Feature (1938): Fallingwater gained international fame when it was featured on the cover of Time magazine on January 17, 1938. This recognition helped solidify its status as an architectural masterpiece and brought widespread attention to Wright’s innovative design24.

Opening as a Museum (1964): After the deaths of Edgar Kaufmann Sr. and Liliane Kaufmann in the 1950s, their son, Edgar Kaufmann Jr., entrusted Fallingwater to the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy in 1963. The house opened to the public as a museum in 1964, allowing visitors to experience its unique design and preserved interiors25.

UNESCO World Heritage Site Designation (2019): Fallingwater was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List on July 10, 2019, along with seven other Frank Lloyd Wright-designed sites. This designation recognized Fallingwater’s significance as a masterpiece of modern architecture and its contribution to cultural heritage12.

These events underscore Fallingwater’s enduring legacy as an architectural icon and its impact on both American architecture and global cultural heritage.

Kaufmanns

The Kaufmanns were a prominent Pittsburgh family known for their business acumen and cultural contributions. Edgar J. Kaufmann was the patriarch, a successful businessman who owned Kaufmann’s Department Store. His wife, Liliane Kaufmann, shared his appreciation for the arts and the outdoors. Their only child, Edgar Kaufmann Jr., played a significant role in the family’s relationship with architect Frank Lloyd Wright, leading to the creation of Fallingwater.

Wright’s Taliesin Fellowship, an apprenticeship program, where Edgar Kaufmann Jr. trained deeply influenced his career, leading him to become a prominent scholar of architecture and design123.

Edgar J. Kaufmann used the grounds at Bear Run for employee camps. In 1916, he began leasing land at Bear Run and established Camp Kaufmann, where a third of his department store employees would spend summers. The camp provided a place for relaxation and outdoor activities such as hiking, swimming, and fishing. However, due to the Great Depression, Kaufmann’s department store had to exit the camp business in 1933, and E.J. Kaufmann assumed ownership of the land with plans to build a modern weekend home, which eventually became Fallingwater1.

Usage of Fallingwater

Weekend Retreat: Fallingwater was primarily used by the Kaufmann family as a weekend home from its completion in 1937 until 1963. It served as an escape from the industrial environment of Pittsburgh, providing a serene setting amidst nature. The family enjoyed various outdoor activities, with Liliane particularly fond of swimming and collecting modern art4.

Cultural Hub: The house also functioned as a cultural hub where the Kaufmanns entertained artists and intellectuals. Notable figures such as Diego Rivera were guests at Fallingwater, reflecting the family’s deep engagement with the arts and culture4. Angelina Jolie, Brad Pitt, and Hillary Rodham Clinton, have visited Fallingwater.

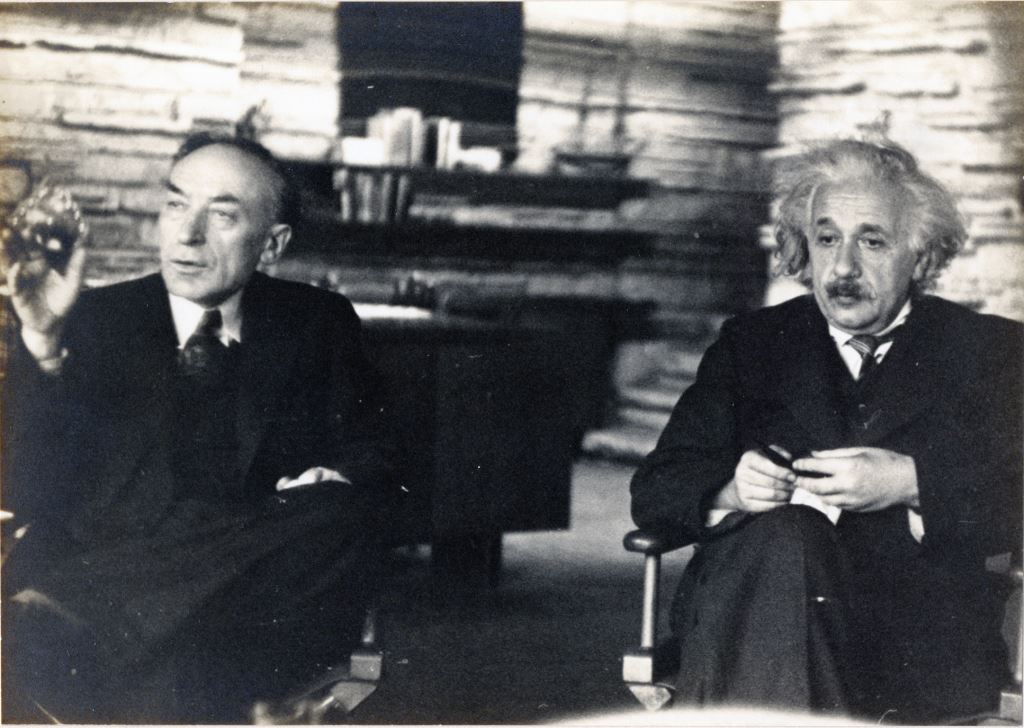

Albert Einstein visited Fallingwater on June 13, 1939. He was attending a conference organized by Edgar Kaufmann to discuss the protection of Jews trapped in Nazi Germany. During this visit, Einstein and Frank Lloyd Wright exchanged a few words, and Einstein was impressed by Wright’s architectural vision and the integration of the house with its natural surroundings.

Preservation Efforts: After Edgar J. Kaufmann’s death in 1955, his son Edgar Jr. inherited Fallingwater. Concerned with its preservation, he donated the property along with surrounding land to the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy in 1963. This act ensured that Fallingwater would be maintained as a public museum, honoring his parents’ legacy134.

The Kaufmanns’ use of Fallingwater highlights their appreciation for art, nature, and architecture, making it a significant part of their personal and cultural legacy.

Building Fallingwater today to code would be a complex and costly endeavor. The original construction cost was $155,000 in 1937, which is equivalent to approximately $3.4 million in 2023 dollars1. However, replicating it today would likely cost significantly more due to modern building codes, materials, and labor costs. The restoration of Fallingwater in 2001 cost about $11.5 million (around $19.8 million in 2023)1. Given these factors, the total cost to build Fallingwater today could easily exceed these figures, potentially reaching tens of millions of dollars.

Fallingwater’s Flowing Tale

Perched above a rushing stream, Wright’s vision, more than just a dream.

Cantilevered over nature’s might, A house that blends with day and night.

Kaufmanns’ fortune built this place, Where art and landscape interlace.

Einstein walked these hallowed halls, Jolie and Pitt admired its walls.

Sandstone quarried from the land, Reinforced concrete, boldly planned.

Glass windows frame the forest view, Where inside and out merge anew.

A museum now for all to see, This organic architecture’s legacy.

From Bear Run’s banks it still inspires, A masterpiece that never tires.

Famous faces come and go, To marvel at the water’s flow.

Fallingwater stands the test of time, A poem in stone, forever sublime.

The cost to take tours of Fallingwater varies by tour type:

- Standard Guided Tour: $30 per adult (plus a $2 service fee) and $16 per child (ages 6-12) 4.

- Special Tours: Prices can go up to $450 per person for exclusive architectural tours 5.

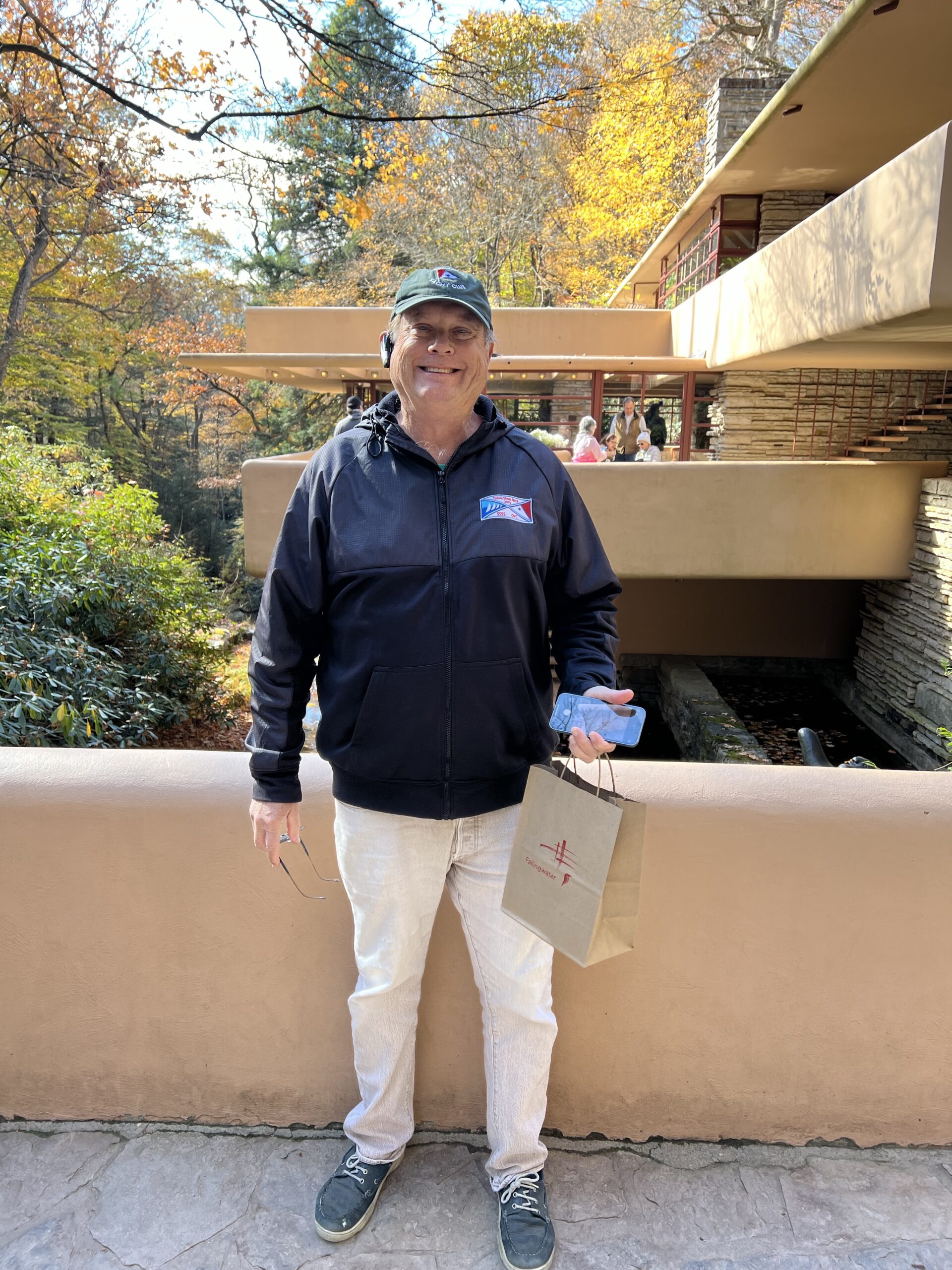

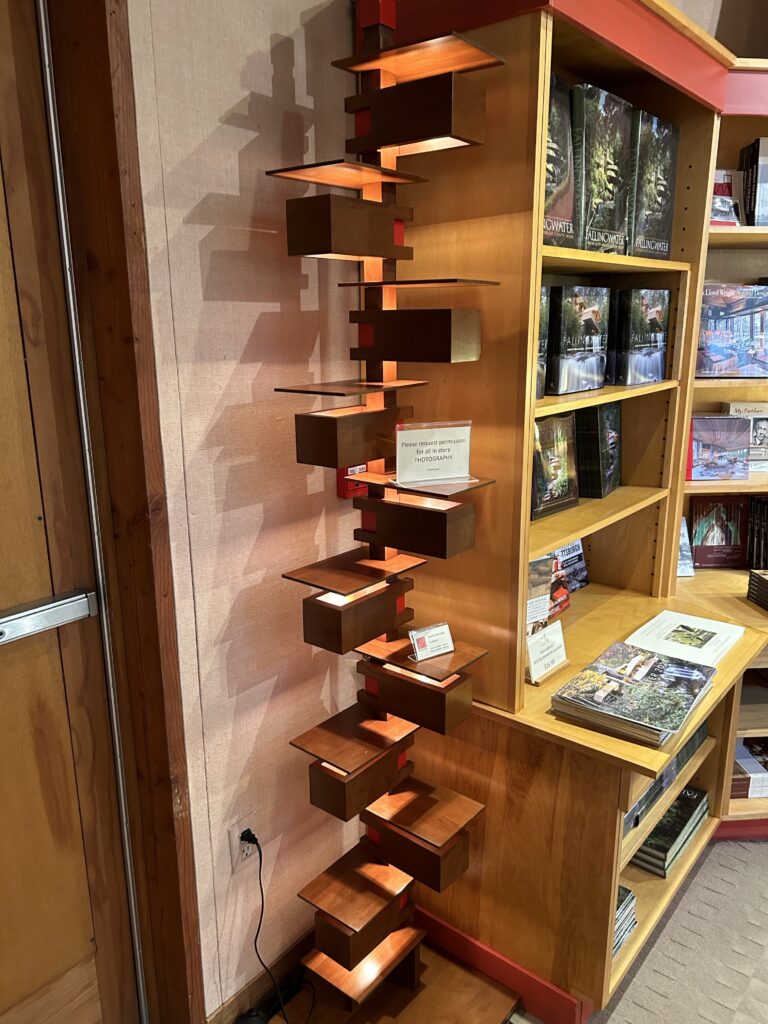

Tours are available daily, except Wednesdays, and typically run from 9:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. Reservations are recommended, especially during peak seasons. It is best to reserve the earliest tour with space available because after the tour you are given access to the property until closing. If you have a late tour it is best to go early anyway, check in and then visit the gift shop (see photos above.) Sometimes you will be able to join an earlier tour owing to late arrivals.

On the tour you are instructed to use the cantilevered walls as stair railings. Wright showed us that a cantilevered design can be used for aesthetic and functional purposes. The above photo allows the railing to appear as if it is floating and seamlessly integrated into the architecture, providing a sleek modern look that provides safety while maintaining design integrity14.

Fallingwater houses a notable collection of artwork that enhances its architectural beauty. Key pieces include:

- Mother and Child: A bronze sculpture by Jacques Lipchitz, located near the plunge pool3.

- Profile of a Man Wearing a Hat: A Conté crayon drawing by Diego Rivera, displayed in the guest bedroom3.

- Fumeur: An aquatint by Picasso, along with a Tiffany lotus lamp and Japanese woodblock prints by Ando Hiroshige, found in various rooms3.

- Méditerranée II: An abstract white marble sculpture by Jean Arp, and Church on the Cliffs VII, a watercolor by Lyonel Feininger, in Edgar Jr.’s study3.

In addition to the previously mentioned artworks, Fallingwater features several other notable pieces:

- Austro-Bohemian Madonna and Child: Carved around 1420 CE, this is one of Liliane Kaufmann’s favorite pieces, located in her fireplace niche3.

- Japanese Woodblock Prints: Including works by Ando Hiroshige and Katsushika Hokusai, gifted by Frank Lloyd Wright3.

- Peter Blume’s The Rock: Commissioned by the Kaufmanns, depicting a scene reminiscent of Fallingwater’s construction5.

These artworks complement the architectural beauty of Fallingwater and reflect the Kaufmanns’ appreciation for diverse artistic styles.