By way of background, the Malheur Indian Reservation was established in 1872 by President Ulysses S. Grant as a home for “all the roving and straggling bands in eastern and southeastern Oregon”4. The reservation was intended to reduce conflict between the Northern Paiute people and the settlers, whose farms and ranches encroached on their territory.

The reservation was located in Malheur County, in southeastern Oregon, and was established for the Northern Paiute Indians2. The reservation was in use for just seven years, from 1872 to 18793. The goal was to concentrate the Indians of the area on this reservation2. The Malheur Reservation included parts of the Blue Mountain, Prairie City, and Emigrant Creek Ranger Districts1.

Some descendants of the Northern Paiutes now live on the Burns Paiute Indian Colony in Oregon2. After closure of the reservation, the Paiutes were scattered between several reservations (Warm Springs, Yakima) and a few remained in that area5. Those who remained received off-reservation allotments under the 1887 Dawes act5. The Burns Paiute tribe was not restored until 19725.

Double O Ranch

After the Bannock War in 1878, many Northern Paiutes were removed by the army to the Yakima Reservation in Washington4. Ranchers and settlers had started to graze their herds on the best meadowlands of the Malheur Indian Reservation, and the U.S. Army had been reluctant to remove the trespassers4. In his annual report in August 1879, Agent W. V. Rinehart, who had fought in the West under General Crook and held negative views of the Natives, opined that the reservation should be discontinued, in part because the support for all agencies in Oregon was4. The Malheur Reservation was discontinued in October 18794.

The Malheur National Wildlife Refuge was established on August 18, 1908, by President Theodore Roosevelt as the Lake Malheur Reservation. The refuge was created in response to a widespread practice at the time: the decimation of breeding birds for their feathers, particularly the great egret11. The name ‘Malheur’ is derived from the French word for ‘misfortune’. The Malheur River, which flows through the region, was so named by French trappers whose property was stolen or ‘misplaced’ near the river. The Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, established by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1908, took its name from this river. The refuge was created to protect habitat for diverse waterfowl and migratory birds1.

In the late 1800s, “plume hunters” eager to harvest colorful and elaborate breeding plumage wiped out entire colonies of waterbirds, killing and plucking the adults and leaving their eggs and chicks to perish. The plumes were considered high fashion in the millinery trade, adorning hats and other couture articles of the era. One of the most persecuted species was the great egret. By the time wildlife photographers William L. Finley and Herman T. Bohlman visited Malheur Lake in 1908, nearly all of these birds had been killed by plume hunters. Their photographs and testimony caught the attention of President Theodore Roosevelt, who quickly moved to formally protect these critical breeding areas from further depredation7.

The refuge is part of the National Wildlife Refuge System, a network of over 560 refuges set aside specifically for fish and wildlife. Managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Refuge System is a living heritage, conserving fish, wildlife, and their habitats for generations to come1.

The Malheur National Wildlife Refuge is of great interest due to its abundant wildlife and natural resources. It is one of the most important refuges for birds in North America, providing habitat for more than 300 avian species. Each year hundreds of thousands of waterfowl and tens of thousands of shorebirds pass through Malheur. The refuge hosts up to half the world’s population of Ross’s Geese, 20 percent of the world’s population of White-faced Ibises, the largest population of Sandhill Cranes of any refuge in the west, and a variety of other globally and continentally important avian populations4. It is an oasis in the high desert of southeastern Oregon for a multitude of birds and other wildlife.

The refuge is recognized as an Important Bird Area (IBA) by the Audubon Society, providing essential habitat for one or more species of birds. It is also a site of recreational activities such as hiking, bird watching, and nature exploration.

The refuge features a visitor Information building and a museum, and offers a variety of recreational opportunities for visitors to enjoy1258. The refuge also offers a variety of recreational opportunities such as hiking, birdwatching, and nature photography7.

What was the protest by ranchers at Malheur National Wildlife Refuge

The protest at the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge began on January 2, 2016, when an armed group of far-right extremists, led by Ammon Bundy, seized and occupied the refuge’s snowed in headquarters. This occupation lasted until February 11, 2016, when law enforcement made a final arrest1.The protest was sparked by the return to federal prison of two Oregon ranchers, Dwight and Steven Hammond, who were convicted of setting fires to public land45. The Hammonds had been sentenced for arson, a ruling that ignited a long-standing dispute over federal land policies in the U.S. West5.

Dwight Hammond and his son Steven Hammond were convicted of arson on federal land in relation to two fires in 2001 and 2006. The 2001 fire, known as the Hardie-Hammond Fire, began after hunters in the area witnessed the Hammonds illegally slaughtering a herd of deer. Less than two hours later, a fire erupted, which was believed to be an attempt to conceal evidence of the deer herd slaughter1. After committing the arson, Steven Hammond called the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) office and claimed the fire was started on Hammond property to burn off invasive species had inadvertently been introduced onto public lands3.

The 2006 fire, known as the Krumbo Butte Fire, occurred during a burn ban while BLM firefighters were fighting other fires started by a lightning storm. Steven Hammond admitted to setting the fires, which endangered public property that abuts private ranch land. This practice, known as “back burning” or lighting “back fires,” is used to prevent wildfires from spreading to private property7.

The Hammonds were convicted of arson in 2012 and were sentenced to five years’ imprisonment. They sought clemency from the U.S. president, and in 2018, President Trump pardoned Dwight L. Hammond and his son, Steven D. Hammond28.

Malheur National Wildlife Refuge was chosen as a protest site because the occupiers sought to advance their view that the federal government should turn over most of the federal public land they manage to individual states, particularly land managed by agencies like the Bureau of Land Management and the United States Fish and Wildlife Service1. The distribution of land ownership in Oregon is approximately as follows:

- Federal land: 53%

- Private land: 37% (combining private industrial, rural, and urban areas)

- State and local government land: 3%

- Other (including Native American lands, Corps of Engineers, National Parks, etc.): 7%2134.

The percentages are approximate and may vary slightly depending on the source and the specific categorization of land types. But in any case, the view that federal public land could be turned over to the State of Oregon ignores the significant lack of administrative capabilities available. There wasn’t any chance of the occupiers demands, regarding the turn over of federal lands to state control, being met.

The occupation was sparked by the return to federal prison of the two Oregon ranchers (the Hammonds) convicted of setting fire to public land4. The protesters believed these ranchers were wrongly convicted and used the occupation as a platform to voice their opposition to perceived federal overreach1.

The protesters, some of whom were loosely affiliated with non-governmental militias and the sovereign citizen movement, claimed that the federal government was overreaching its authority and infringing on the rights of local ranchers16.

The protesters took control of the refuge’s headquarters after a peaceful public rally in the nearby city of Burns1. They set up defensive positions at the refuge and hosted a news conference, promising reporters that an end to the occupation would come with the fulfillment of their demands12. These demands included the return of public lands to local control and the cessation of what they perceived as federal tyranny in the rural West3.

The occupation drew national attention and was marked by a series of events, including a “signing ceremony” where the protesters claimed to have recruited ranchers to stop paying the federal government grazing fees2. The protesters encouraged ranchers to tear up their government grazing contracts and claimed that the refuge had taken over the space of 100 ranches since the early 1900s6.

Ammon Bundy, the leader of the 2016 occupation of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, is the son of Nevada rancher Cliven Bundy, who reportedly owes more than $1.3 million in grazing fees to the U.S. Bureau of Land Management1. prior to the occupation, he had lost a home in a short sale and was behind on his property taxes2. Ammon Bundy currently resides in Emmett, Idaho, and owns a truck repair company2. It is unclear if he is still involved in ranching activities. Bundy asked the Oath Keepers to the protest and ran for governor of Idaho in 2022.

PHOTOGRAPH BY RICK BOWMER, ASSOCIATED PRESS

Cliven Bundy, a Nevada rancher, has been grazing his cattle illegally on federal land since 1993 and reportedly owes more than $1.3 million in grazing fees to the U.S. Bureau of Land Management16.

Despite numerous court decisions and legal opinions, Bundy has refused to recognize federal control of public lands in Nevada, where his cattle have grazed illegally in and around the Lake Mead National Recreation Area since the 1990s5.

As of 2023, Bundy’s cattle continue to graze illegally on federal land that has been permanently closed to livestock grazing since the mid-1990s to protect the endangered desert tortoise and other rare species1. The Bureau of Land Management, which oversees the land that Mr. Bundy’s cattle continue to graze illegally, has not disclosed why Mr. Bundy has been allowed to run roughshod over rules other ranchers follow or how much he owes in fees and fines to federal taxpayers1.

In 2014, the back fees had accumulated to more than $1 million7. Despite the significant amount owed, the federal government has not taken decisive action to collect the fees. Some public lands advocates argue that the federal government could easily get this situation under control by issuing bench warrants holding Bundy in contempt of court for trespassing and refusing to pay grazing fees, or putting a lien on Bundy’s property7. However, as of now, no such actions have been taken.

During the 41-day occupation of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge by Ammon Bundy and his group, significant damage was done to the refuge’s facilities. The specific damages included:

- Trashed Buildings: The occupiers left behind piles of garbage, abandoned camping gear, food, and alcohol. Offices were turned upside down, with possessions missing7.

- Damaged Facilities: The occupiers caused physical damage to the buildings, including broken walls7.

- Compromised Septic Systems: The septic system at the refuge was compromised during the occupation7.

- Excavated Grounds: The grounds of the refuge were excavated, causing further damage7.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service estimated that it would spend $1.7 million to restore damaged property and replace missing items7. The total cost of the occupation for the federal agency was estimated to be at least $6 million, which could grow as workers continued to assess and repair the damage7. This $6 million is in addition to the more than $3 million that Oregon government agencies reported spending on the occupation7.

Defendants guilty of occupying the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge agreed to pay a total of $78,000 in restitution2. This agreement was between the U.S. Department of Justice and 13 defendants who were either found guilty or pleaded guilty to conspiracy to impede federal officers who worked at the refuge from doing their jobs2. The restitution agreement must be signed off by U.S. District Court Judge Anna Brown before it becomes official2.

One person died during the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge occupation. Robert LaVoy Finicum, a spokesman for the occupiers, was shot and killed during an arrest attempt on January 26, 20165.

The protest ended with the arrest of the remaining occupiers and the subsequent acquittal of the leaders, including Ammon and Ryan Bundy, of federal charges for their role in the protest5. The Hammonds, whose sentencing sparked the occupation, were pardoned by U.S. President Donald Trump in 20185.

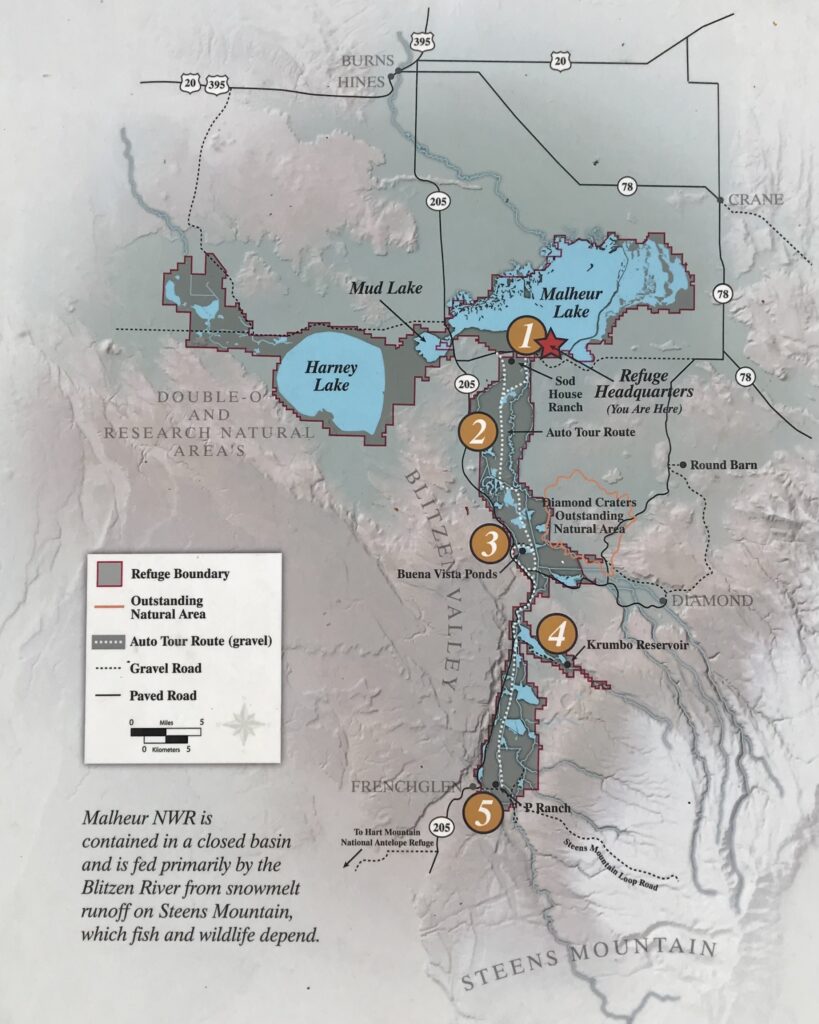

There was a ranch on the land now used for the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge. The Sod House Ranch, built by Peter French, a 19th-century cattle baron, was located south of Malheur Lake in the refuge area. The ranch was part of the French-Glenn Livestock Company, which eventually covered over 140,000 acres6.

Not all occupiers were from out of state, but the group’s leader, Ammon Bundy, was from Nevada1. The occupation attracted individuals from various locations, some of whom were affiliated with non-governmental militias and the sovereign citizen movement1.

Birds at Malheur National Wildlife Refuge

The Malheur National Wildlife Refuge is a crucial stop for hundreds of thousands of birds migrating along the Pacific Flyway, which stretches from Alaska to Patagonia. The refuge is home to over 320 species of birds and 58 species of mammals, making it one of the most productive waterfowl breeding areas in the United States45.

Migratory Waterfowl and Shorebirds

The migratory waterfowl and shorebirds that stop at the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge vary by month:

- February – April: This period marks the beginning of the major songbird migration, which reaches its peak in late May. Birds such as warblers, vireos, tanagers, and buntings concentrate in areas like the Refuge Headquarters, Benson Pond, and P Ranch7.

- May – June: By early June, the songbird migration wanes, leaving the refuge to the many local breeding species7.

- July – August: This period is relatively quiet in terms of migratory birds.

- September – October: Warblers, sparrows, and other songbirds reach their autumn peak at Malheur from mid-August through late September. Swainson’s and red-tailed hawks are present, and bald eagles and rough-legged hawks begin arriving in mid-October7.

- November – January: This period is also relatively quiet in terms of migratory birds.

Resident Birds The Malheur National Wildlife Refuge is home to several species of owls, including the Great Horned Owl, Short-eared Owl, Long-eared Owl, Barn Owl, and Burrowing Owl6. These owls are residents of the refuge and can be spotted throughout the year.Please note that the specific months and species mentioned are not exhaustive, and the presence of different species can vary based on factors such as weather conditions and changes in habitat. For the most accurate and up-to-date information, consider visiting birding websites or contacting local birding groups or the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

what are some of the most common raptor species found at malheur national wildlife refuge

The Malheur National Wildlife Refuge is home to a variety of raptor species, making it a popular destination for birdwatchers. Some of the most common raptor species found at the refuge include:

- Red-tailed Hawk: This species is a common sight at the refuge and can be seen throughout the year25.

- Northern Harrier: Also known as the Marsh Hawk, this raptor is common during summer and migration in open habitats at the refuge25.

- American Kestrel: This small falcon can be seen perched on power lines and fence posts throughout the refuge24.

- Bald Eagle: This iconic bird, the national symbol of the United States, can also be found at the refuge45.

- Swainson’s Hawk: This migratory bird can be seen at Malheur in the fall5.

- Ferruginous Hawk: This species is also spotted at the refuge7.

- Golden Eagle: This majestic bird is another raptor species that can be found at Malheur4.

- Prairie Falcon: This species is most common in rimrock country where they nest, but may travel great distances in search of prey2.

Please note that the presence of different species can vary based on factors such as weather conditions and changes in habitat. For the most accurate and up-to-date information, consider visiting birding websites or contacting local birding groups or the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service1234567.

In the land of the setting sun, where the rivers run, The French once roamed, their journey far from done. But fortune turned its back, their land was lost, They named it ‘Malheur’, a reminder of the cost.

A struggle then ensued, ranchers staking claim, On the fertile plains, in the wild west game. The egrets soared above, their plumes like snow, Caught in the crossfire, in the struggle below.

Then came a decree, from President Grant’s hand, To move the native tribes, to this contested land. The Malheur Reservation, a home for the Paiute, A fleeting promise, before the white man’s pursuit.

But the land was rich, and the cattle needed grazing, The promise was broken, the act truly amazing. From reservation to refuge, the land transformed, A sanctuary for the birds, as the egrets swarmed.

Then came the cowboys, with their protest loud, Against the federal rule, they stood proud. But the standoff turned tragic, a spokesman fell, In the land of Malheur, where the egrets dwell.

Yet nothing was resolved, the struggle The ended, The land still contested, the wounds not mended. But though it all, the birds remain, In the land of Malheur, amidst the distress and pain.

In the poem, the egrets symbolize purity, divine power, and grace4. These elegant birds are known for their striking beauty and have been admired by various cultures throughout history. The poem highlights the struggle of ranchers and the plumes of egrets, which were once targeted for their feathers. The egrets represent the rare and beautiful aspects of nature that have endured despite human conflicts and interventions. Their presence in the poem serves as a reminder of the resilience and grace of the natural world, even in the face of adversity and change.

Diamond Craters Outstanding Natural Area and Round Barn

The Diamond Craters Outstanding Natural Area, a geologically youthful lava field located 52 road miles south-southeast of Burns in southeastern Oregon, is managed as an Outstanding Natural Area by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management.

The Diamond Craters, located near Diamond, Oregon, is a monogenetic volcanic field about 40 miles southeast of Burns, Oregon. The field consists of a 27-square-mile area of basaltic lava flows, cinder cones, and maars7.

The name Diamond, applied to the lava field and the nearby village of Diamond, originated with Mace McCoy’s Diamond Ranch and its diamond-shaped branding iron9.

The Diamond Craters is a unique sight in Oregon, offering an intriguing display of volcanic features11.

At the turn of the century, the community of Diamond was growing into a major merchandising outlet for ranchers, sheep men, and travelers15. It is located west of Oregon Route 205 and south of Malheur Lake, 52 miles south-southeast of Burns by highway1.

Diamond Lake, which is a short distance from Diamond, is known for its trout population12.

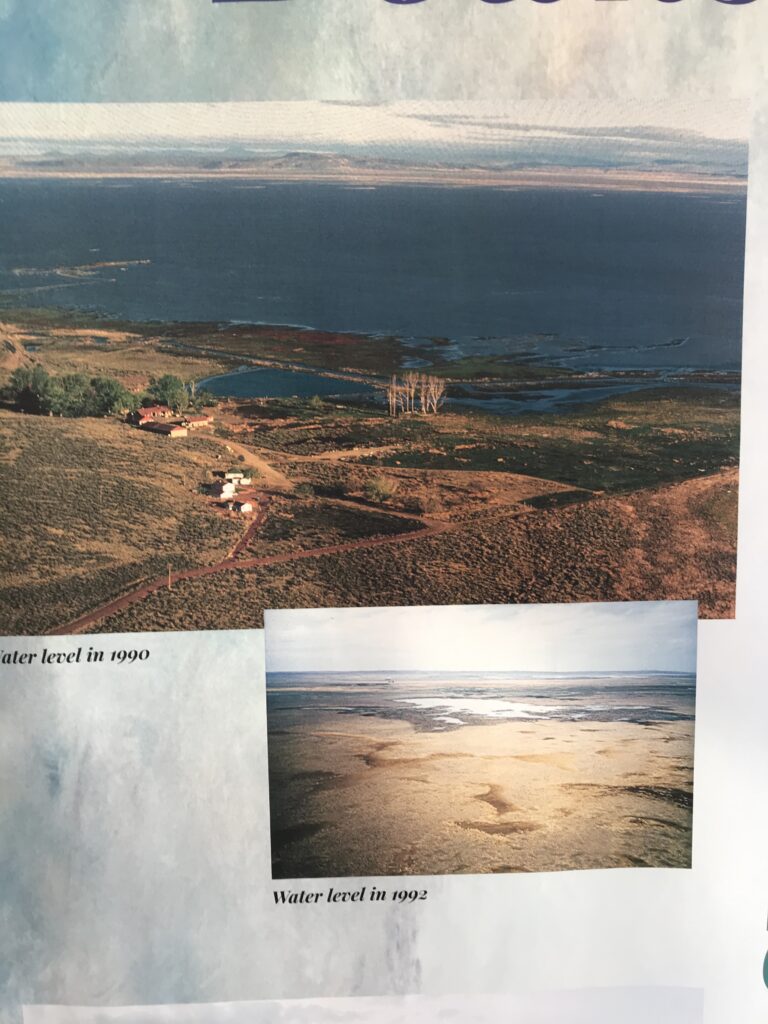

it’s important to note that the region has experienced multiple droughts in the early 21st century, which can affect the local wildlife and agriculture714

In summary, Diamond, Oregon, has a rich history tied to the Diamond Ranch, the Diamond Craters, and Diamond Lake. Each of these landmarks contributes to the unique character and significance of the area. The following describes the Round Barn.

The story of the Round Barn in Diamond, Oregon, is tied to Peter French, a cattle rancher who arrived in the area in 1872.

“Cattle King” Pete French arrived here in 1872 and claimed great chunks of high desert land for himself and his California-based employer, Dr. Hugh Glenn.

In California, cattle owners were required to keep their cattle from ranging on farmers land. In Oregon, the opposite was true: farmers had to build fences to keep cattle out, even where adjoining lands were unclaimed. The open range made ranching far more lucrative in Oregon than California.

French began amassing land and cattle, and by the mid-1880s, he had built a significant livestock empire. . By the 1880s, he was working tens of thousands of head of cattle with the help of 50-80 ranch hands.

He marked his ownership by simply building fences around the land, then went on to use it as he saw fit.

The Round Barn was used to train wild horses to pull long wagon trains full of wool, hay, and supplies to market in Oregon City.

This type of barn is unique in today’s landscape, but during 1880–1920, round barns became popular in the Midwest where they were promoted as being efficient for progressive methods of farming2.

The Round Barn was constructed sometime in the late 1870s or early 1880s. It was used to provide covered space for training and exercising horses during the winter.

-French-Glenn employee John Culp

After French’s death in 1897, ownership of the barn passed to the French-Glenn Livestock Company, and in the early 1920s, the barn was acquired by the Jenkins family.

– Margaret Justine LoPiccolo, 1964

The family used it for several decades for grain and equipment storage until they donated it to the Oregon Historical Society.

The barn was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 19714.Today, the Peter French Round Barn is administered by the Oregon State Parks system and is open to the public4.

The P Ranch

Pete French’s years of aggressive tactics caught up to him in 1897.

“French had many enemies … and had often expressed the belief that he would be murdered someday.”

-Portland Oregonian, December 29, 1897

In the late 1880s, homesteader Edward Oliver made a 160-acre claim on a section of French-Glenn’s “P” Ranch along the contested Malheur Lake shoreline. The shoreline had been resurveyed and was open for settlement. French claimed the land and tried to throw Oliver and his homesteading neighbors out. This time, French lost in court.

In the next battle of their 10-year war, Oliver successfully asked the county court for a road easement so he didn’t have to go six miles out of his way to avoid trespassing. Furious, French sued the county for the road’s removal.

On December 26, 1897, the frustrated Oliver decided to avoid the six-mile detour and rode onto French-Glenn land. Pete French was moving some cattle that day, and the two men met. Facing each other on horseback, they argued bitterly. French hit Oliver with a willow whip and started to ride away. “He got only a few feet when Oliver drew a pistol and shot him,” reported the Sacramento Record.

“Thus ended the life of Peter French, a man of many admirable qualities of mind and heart, but whose tyrannical and overbearing temper brought about his own ruin.” – Cattle baron and French competitor David Shirk

The Oregon courts and public opinion had turned against the big cattle barons. When Oliver was tried for murder, the jury found him innocent.

The French-Glenn “P” Ranch was sold in 1906. The land eventually reverted to public land, and in 1908 it was set aside by President Theodore Roosevelt as Malheur National Wildlife Refuge.