Billy Frank Jr., a prominent Nisqually tribal member, was a dedicated Native American environmental leader and treaty rights activist who played a pivotal role in advocating for tribal fishing rights on the Nisqually River in Washington state during the 1960s and 1970s. Born on March 9, 1931, in Nisqually, Washington, Billy Frank Jr. grew up on the Nisqually River at Frank’s Landing, where his father purchased land after being displaced from their reservation due to the expansion of an Army base nearby2.

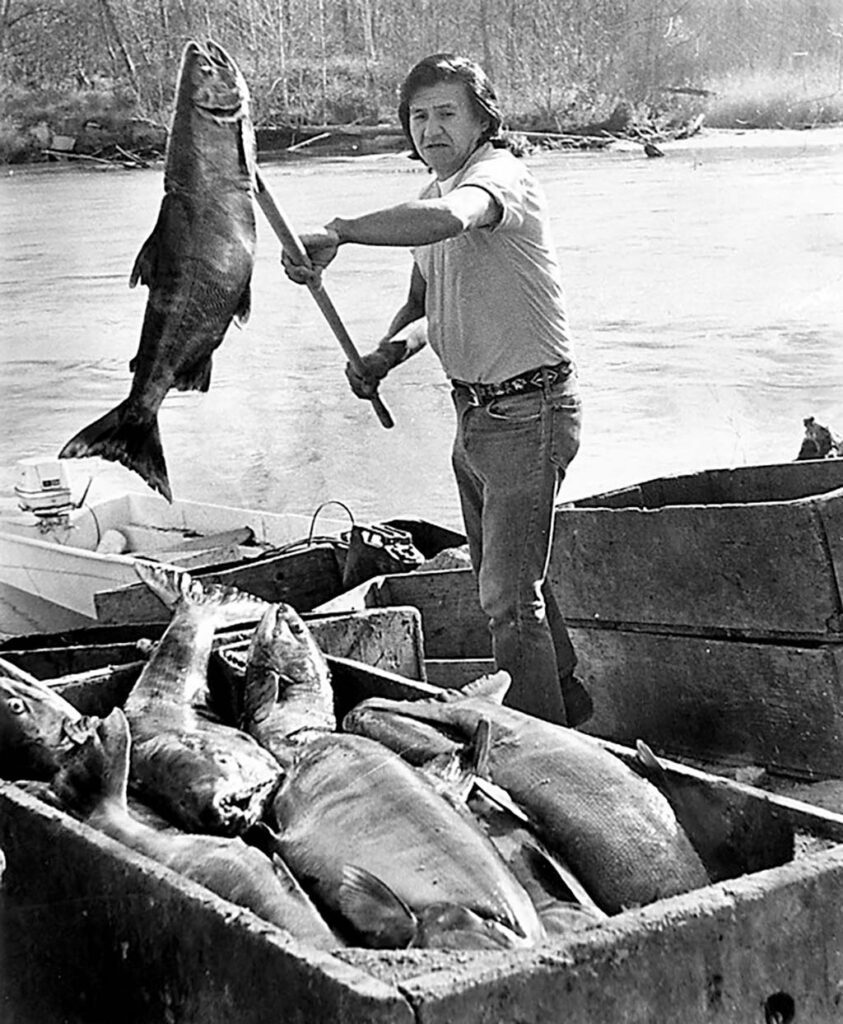

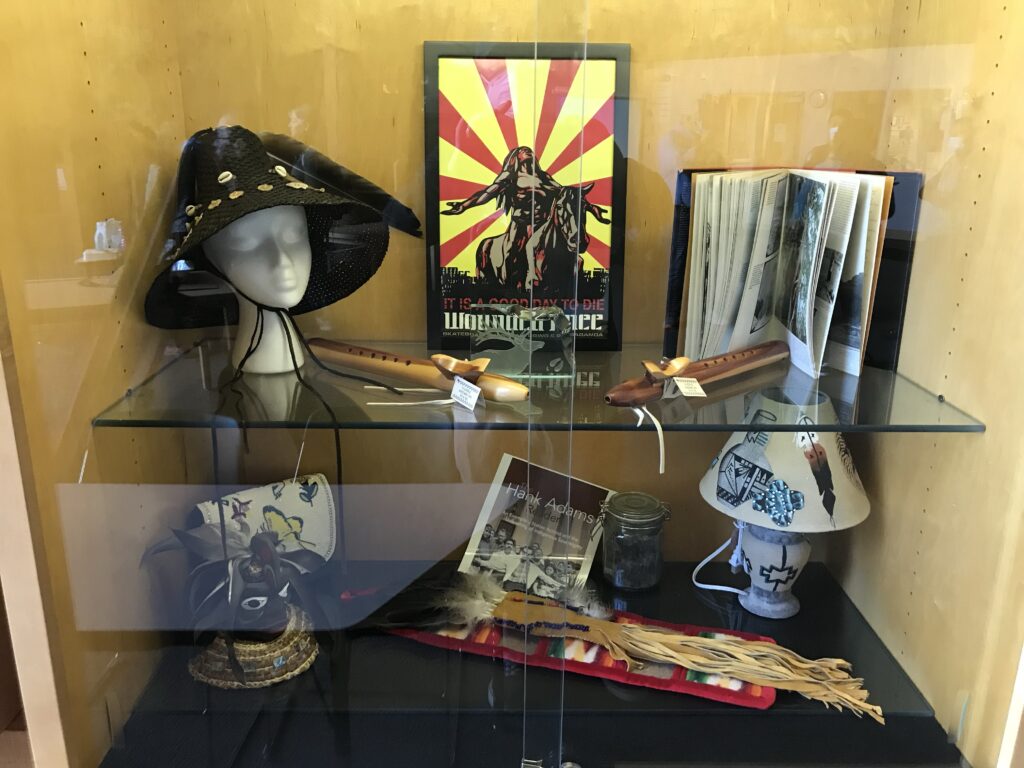

Frank’s activism began early in life when he was first arrested at age fourteen while fishing on the Nisqually River, sparking a lifelong commitment to civil disobedience and advocacy for tribal fishing rights. He participated in “fish-ins,” civil rights protests organized by the Survival of the American Indian Society (SAIA), which aimed to assert tribal fishing rights guaranteed by treaties negotiated with the U.S. government in the mid-1850s4.

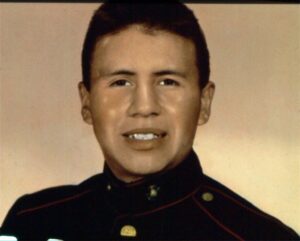

In the 1950s, Billy Frank Jr. served as a military policeman in the U.S. Marine Corps during the Korean War3. His service during this conflict exemplified his dedication to duty and his commitment to defending his country. After his military service, Billy Frank Jr. returned to Washington state, where he continued to advocate for tribal rights, environmental protections, and the preservation of Indigenous culture.

During the Fish Wars of the 1960s and 1970s, Frank’s leadership in the fish-ins drew national attention and celebrity support, with notable figures like Marlon Brando participating in demonstrations. These protests were instrumental in highlighting the struggles faced by Native American tribes in exercising their fishing rights off-reservation and led to legal battles that culminated in the landmark Boldt Decision of 1974. This ruling affirmed the treaty tribes’ rights to co-manage salmon resources with Washington State and reaffirmed tribal entitlement to half of each year’s fish harvest4.

In 2014, Billy Frank Jr. passed away, leaving behind a legacy of advocacy for tribal treaty rights, environmental protections, and Indigenous culture preservation25.

Billy Frank Jr.’s unwavering dedication to tribal fishing rights and environmental conservation earned him widespread recognition. He served as Chairman of the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission for over thirty years, promoting cooperative management of natural resources and advocating for tribal sovereignty.

In November 2015, he was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama for his lifelong commitment to Native rights and environmental stewardship4.

The legacy of Billy Frank Jr. continues to inspire environmental activism and bridge-building between Western and Native American societies, emphasizing the importance of preserving natural resources and upholding tribal treaty rights for future generations5.

[Charles] Wilkerson’s history- written at the request of Billy Frank Jr., who died in 2014- tells the broad saga of Indian fishing rights in Washington, highlighting significant events and individuals-like lawyer Jack Tanner, ’55, the president of the NAACP’s Washington chapter. He was hired by the tribes to fight their case in court. And another, anthropologist Barbara Lane, ’53, who provided expert testimony at the trial about the culture and history of the tribes, the circumstances around the Medicine Creek treaty and contemporary tribal lives and values.

Wilkerson describes Lane as “the most important witness in the trial.”

In his U.S. District Court decision, Judge George Boldt affirmed the tribal members’ rights to fish and guaranteed them 50% of the harvest through their traditional fishing grounds and as co-man-agers of the state’s fisheries. One outcome of the decision is tribal governments’ increased role in protecting salmon and steelhead populations and their habitat here in Washington.

“This and other seminal cases from the Northwest became precedent for cases across the country,” says Ned Blackhawk 99, a member of the Te-Moak Tribe of Western Shoshone and scholar of Native American history. “The Boldt decision was among the most important exertions of Native American treaty rights in American history. It was tremendously generative and controversial.” What unfolded in Washington set precedent and encouraged tribes across North America to affirm their own sovereign and treaty rights, he adds.

To honor Frank, the Washington Legislature voted to install a statue of him in the National Statuary Hall in Washington, D.C. “There’s going to be a lot of attention this year as Washington turns the story of the Boldt decision into a kind of celebration,” White says. “The story starts with the struggle and ends with Billy Frank Jr. in the U.S. Capitol.” What shouldn’t be forgotten, he adds, is that state and national leaders *spent years trying to cut off funding to the Indian fisheries community and sought to strip the tribes of power.”

The 9-foot-high bronze statue of Billy Frank Jr. by sculptor Haiying Wu, 96, is scheduled to be unveiled in 2025.

Tribes, Treaties and Justice The Boldt Decision, which turns 50 this year, reaffirmed tribal fishing rights in Washington and marked a turning point for tribal sovereignty by Hannelor Sudermann pg 12 UW MAGAZINE

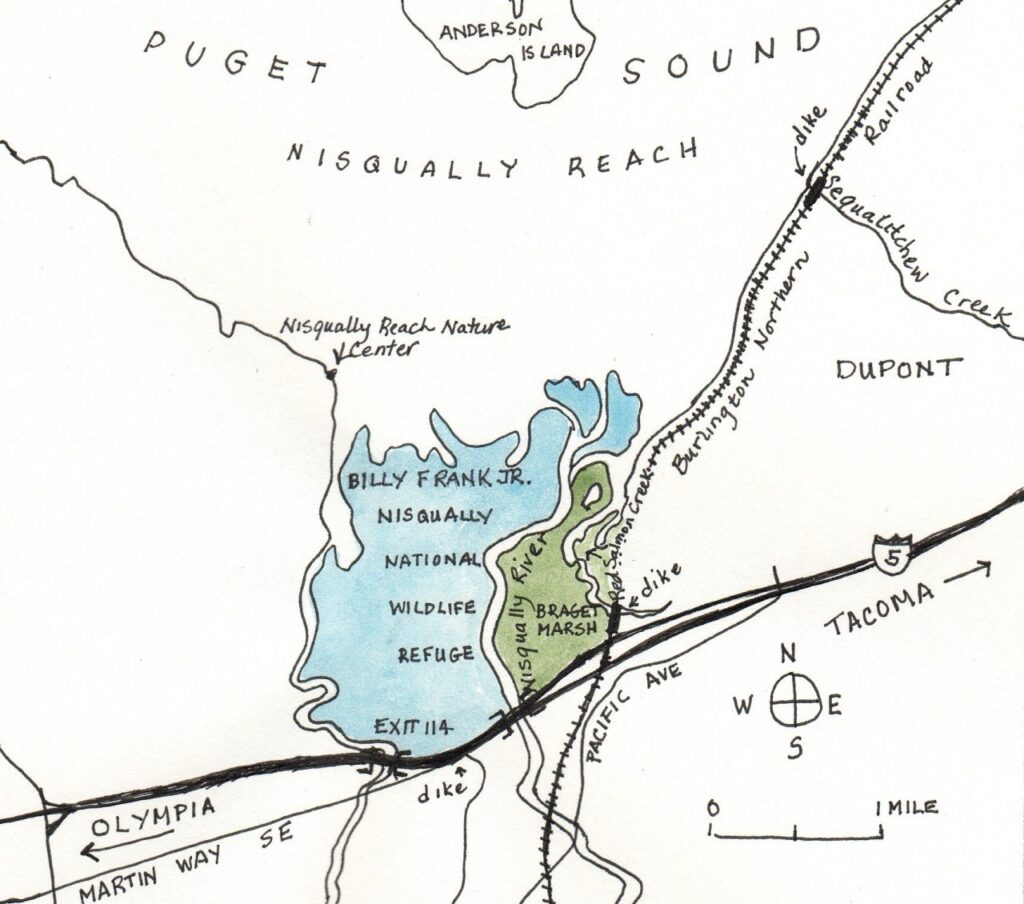

Nisqually River and Medicine Creek

The Nisqually River and Medicine Creek are closely linked in the history of the Nisqually tribe and Billy Frank Jr.’s activism for Indigenous fishing rights:

- Geographical Proximity: The Nisqually River flows through the Nisqually Indian Reservation, near Fort Lewis, and into Puget Sound, while Medicine Creek, where the Treaty of Medicine Creek was signed, is located near the Nisqually River delta1.

- Treaty of Medicine Creek: The Treaty of Medicine Creek, signed near Medicine Creek in 1854, was a significant event that impacted the Nisqually tribe’s fishing rights and land ownership, setting the stage for future struggles over tribal sovereignty and fishing rights4.

- Historical Significance: The signing of the treaty near Medicine Creek marked a pivotal moment in the relationship between Washington territory and the native population of Puget Sound, leading to changes in land ownership and tribal rights that influenced the Nisqually tribe’s history and their ongoing fight for fishing rights4.

- The 2001 Nisqually earthquake occurred at 10:54:32 local time on February 28, 2001, with a moment magnitude of 6.8 and a maximum Mercalli intensity of VIII (Severe). The epicenter was in the southern Puget Sound, northeast of Olympia, but the shock was felt in Oregon, British Columbia, eastern Washington, and Idaho. The earthquake resulted in one death from a heart attack and several hundred injuries1345.

Traveling from Medicine Creek to the Nisqually River involves a journey of approximately 15 miles, which can take between 3 to 7 hours depending on the mode of transportation and specific starting and ending points1.

The Nisqually River, where Billy Frank Jr. was arrested for fishing in his youth, holds historical significance for the Nisqually tribe and played a central role in the fish wars and the fight for Indigenous fishing rights5.

On December 26, 1854, James McAllister, an early settler whose homestead was located nearby, was present during the treaty council held near a Nisqually village. The creek, known as She-nah-nam Creek by the natives and Medicine Creek by white settlers, is now generally referred to as McAllister Creek. James McAllister and other settlers were witnesses to the treaty signing between U.S. officials and tribal representatives from the Puyallup, Nisqually, and Squaxin Island tribes345. The name “Medicine Creek” does not imply that there was actual medicine at the creek but rather reflects the historical context of the treaty signing and the subsequent renaming of the creek in honor of James McAllister, a prominent figure in that period.

The proximity of Medicine Creek to the Nisqually River underscores the interconnected history of these locations in shaping the Nisqually tribe’s heritage and their enduring struggle for Indigenous fishing rights.

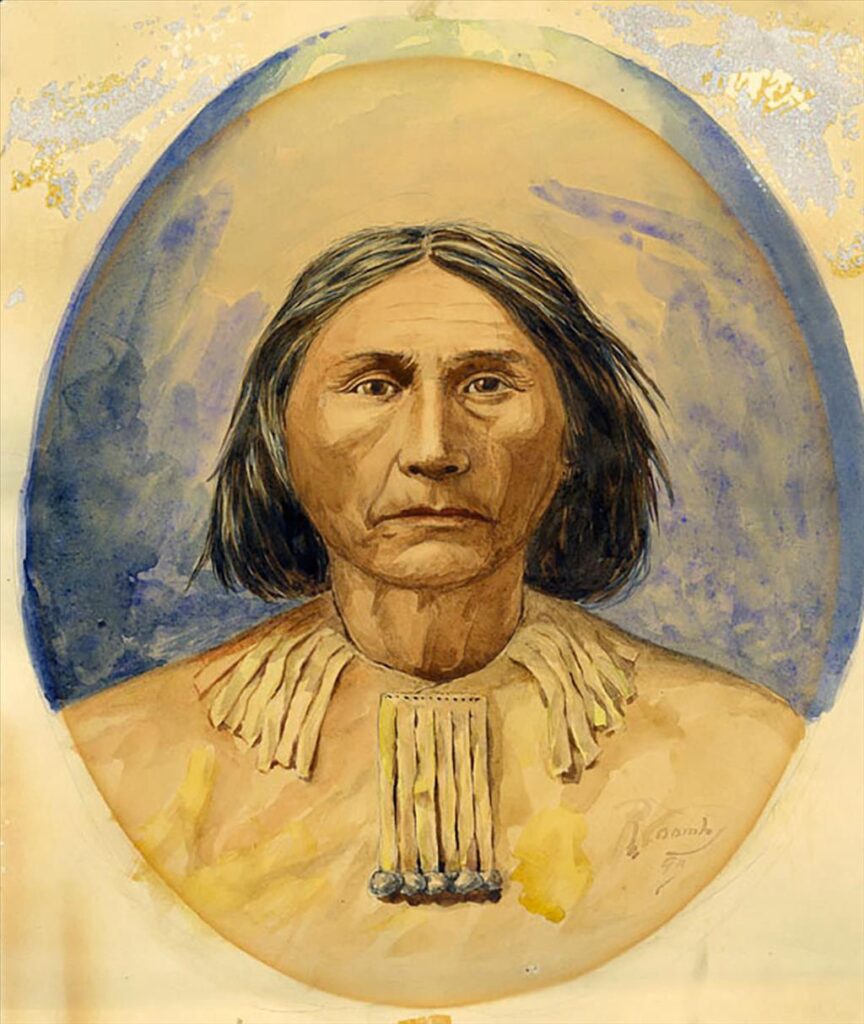

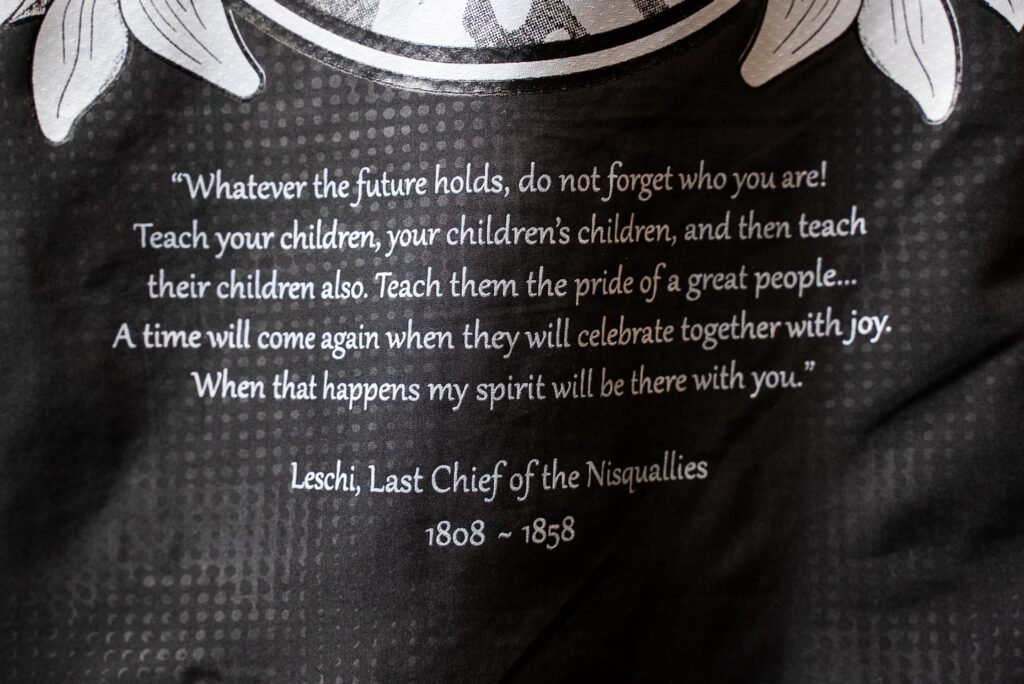

Leschi

Leschi, a respected chief of the Nisqually Indian Tribe, played a significant role in the history of the tribe and the struggle for Indigenous rights. Leschi, born in 1808 near present-day Eatonville, Washington, was appointed by Washington Territory’s first governor to represent the Nisqually and Puyallup tribes during treaty talks near Medicine Creek in 18543.

Outraged by the inadequate reservation imposed by the treaty, Leschi took up arms and became a leading chief of a fighting force comprising members of several Puget Sound tribes. Despite being outgunned and outmanned, Leschi and his followers retreated to the Kittitas Valley in the spring of 18563.

Leschi’s story is one of resilience, leadership, and resistance against unjust treaties that threatened tribal sovereignty and way of life.

Leschi .. is famous for his part in the Battle of Seattle. Native Americans, upset by the 1854 Medicine Creek Treaty which gave their lands to the whites, attacked the tiny village of Seattle on January 26, 1856. Two white settlers and many Indians were killed.

Leschi was a leader who resisted sending fellow Native Americans to reservations. He and 38 men in six canoes went south to Fox Island to take John Swan, the agent in charge of the reservation, away with them.

Leschi was captured by Captain Maloney of the steamer Beaver from Fort Steilacoom, and sent to the reservation.

The following day Leschi left the reservation. It wasn’t long before he was captured again and tried in a civilian court for a “murder” he committed during the Indian Wars.

He was hanged later, after he had been chained in public view for months until he became weak and emaciated. His executioner said he felt he was “hanging an innocent man.”

Leschi’s efforts to gain a more favorable treaty for his people bore fruit after his death when Governor Isaac Stevens signed a treaty giving the Native Americans better land than provided for in the Medicine Creek Treaty.

Gunkholing in South Puget Sound with Jo Bailey and Carl Nyberg pg 75

The Nisqually Tribe, a Lushootseed-speaking Native American tribe in Washington state, has a rich history deeply intertwined with the Nisqually River valley and the struggle for Indigenous rights:

- Origins: Legend states that the Squalli-absch, ancestors of the modern Nisqually Tribe, migrated north from the Great Basin, crossed the Cascade Mountains, and established their first village near Skate Creek4.

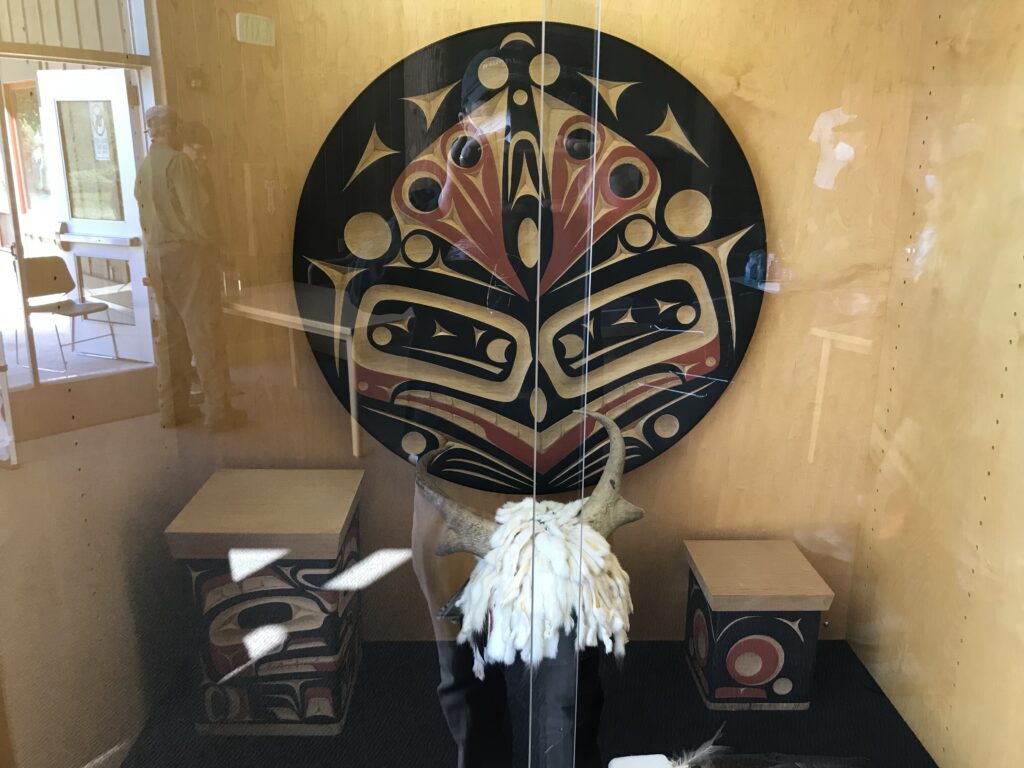

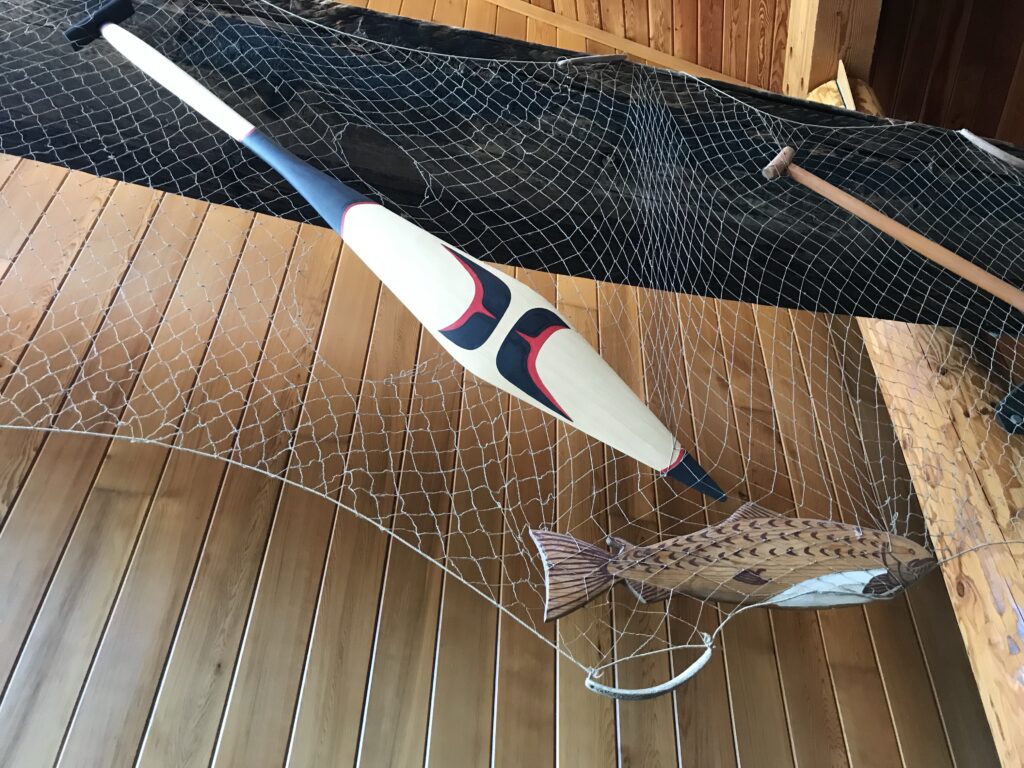

- Cultural Significance: Fishing has been a cornerstone of Nisqually culture for millennia, with salmon serving as not just a dietary staple but a cultural foundation. The tribe’s stewardship of the Nisqually River fisheries and operation of fish hatcheries underscore their deep connection to the land and waterways4.

- Treaty of Medicine Creek: The tribe moved onto their reservation east of Olympia in 1854 after signing the Medicine Creek Treaty. Chief Leschi’s opposition to the treaty led to conflict with the US Army34.

- Cultural Significance: The Nisqually people have been fishing for thousands of years, with salmon being central to their diet and culture. They are stewards of Nisqually River fisheries and operate fish hatcheries14.

- Environmental Stewardship: The Nisqually Tribe, in collaboration with various groups, played a crucial role in preventing the construction of a port at the mouth of the Nisqually River, safeguarding fish species and their treaty rights. This effort was part of the broader Fish Wars movement, highlighting the tribe’s commitment to protecting marine resources3.

- Historical Context: The establishment of the Toliva Shoal Marine Preserve and the Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge reflect a legacy of resilience and environmental advocacy among the Nisqually people. These efforts align with their traditional values and commitment to preserving natural resources for future generations34.

- Contemporary Life: The tribe has grown to over 650 enrolled members, with most residing on or near the reservation. They are known for their environmental stewardship programs and economic ventures like the Red Wind Casino35.

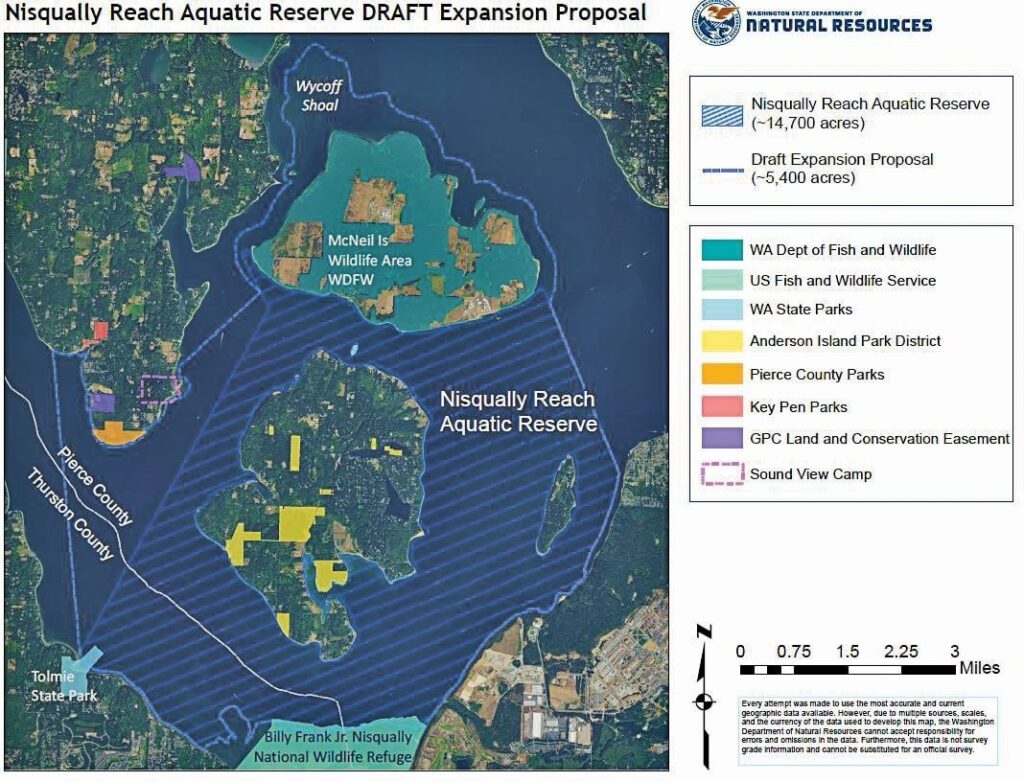

The Toliva Shoal Marine Preserve provides habitat protection for various marine species. This preserve, established in 2006, covers an area of 65.67 hectares and is classified as a low citizen engagement area with low dive usage5. The marine preserve aims to safeguard the rocky reef habitat found within its boundaries, which is utilized by ESA listed rockfish and is popular among divers5. Additionally, the Toliva Shoal Race, a sailing event held in the area, attracts numerous boats and participants, making it a significant event in the Puget Sound sailing community3. The waters surrounding the Toliva Shoal buoy are closed to fishing for food fish from June 16 through April 30 and closed to rockfish year-round within 500 yards of the buoy1.

The Toliva Shoal Marine Preserve holds historical significance for the Nisqually Tribe due to its role in environmental conservation and cultural preservation:

- Environmental Conservation: In the 1960s, the Nisqually Tribe, along with the Nisqually Delta Association and other groups, successfully opposed the construction of a port at the mouth of the Nisqually River. This action aimed to protect fish species and uphold the tribe’s treaty rights, marking a pivotal moment in environmental activism and resource protection4.

- Cultural Preservation: The Nisqually people have a deep-rooted connection to fishing, with salmon being a vital part of their culture and heritage. The tribe’s efforts to restore estuaries and protect salmon habitats reflect their commitment to preserving traditional practices and sustaining their way of life4.

The naming of the Toliva Shoal Marine Preserve after the Nisqually Tribe is a testament to their enduring presence in the region, their advocacy for environmental stewardship, and their ongoing efforts to protect natural resources critical to their cultural identity.

The history of the Nisqually Tribe reflects a legacy of resilience, cultural preservation, and ongoing efforts to protect their land, resources, and heritage.

The Nisqually people, also known as the Squalli-absch, have a rich history deeply rooted in the Nisqually River basin in western Washington state:

- Origins: Legend states that the Squalli-absch ancestors migrated north from the Great Basin, crossed the Cascade Mountains, and established their first village near Skate Creek4.

- Traditional Lands: The Nisqually’s traditional lands spanned from Puget Sound to Mount Rainier, with their current reservation located by the Nisqually River in Thurston County2.

- Population: In 1780, there were around 3,600 Nisqually individuals. By the early 20th century, this number had decreased to 110. In more recent times, the 2000 census reported 460 Nisqually individuals and 697 with some Nisqually heritage2.

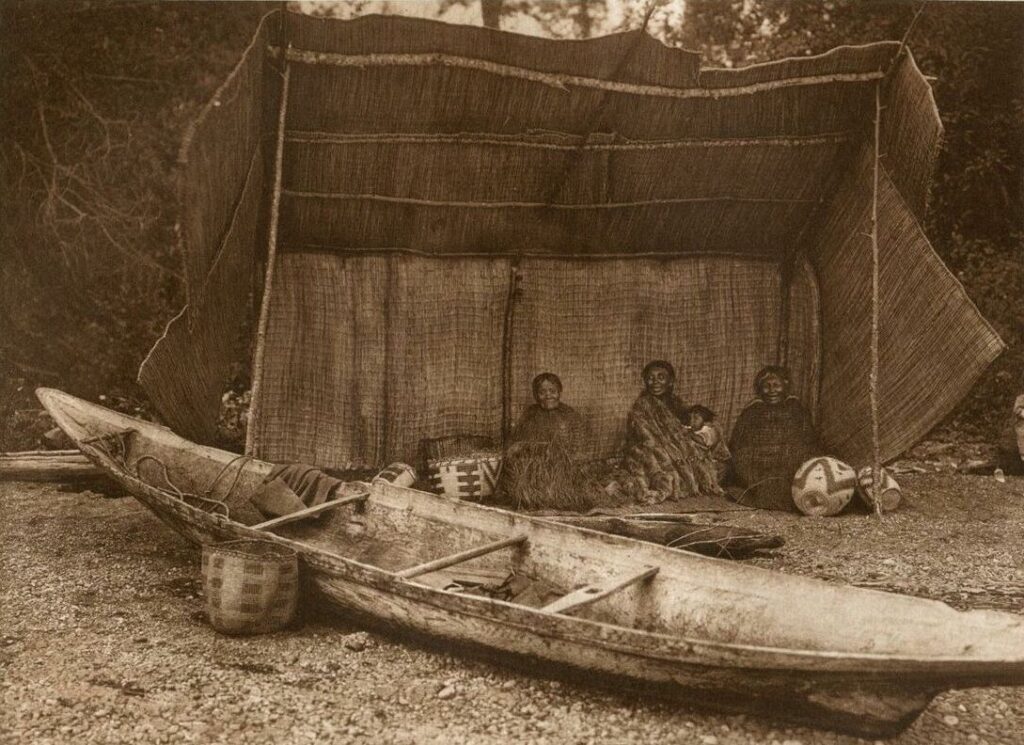

- Cultural Practices: The Nisqually people thrived on the natural resources of their vast tribal lands, engaging in fishing, hunting, and special rituals. Salmon has been central to their diet and culture24.

- Historical Events: The tribe moved onto their reservation in 1854 after signing the Medicine Creek Treaty. Chief Leschi’s opposition to the treaty led to conflict with the US Army4.

The Nisqually people had significant relationships with other tribes in the region, fostering cultural connections and trade networks:

- Cultural Links: The Nisqually people had cultural ties with tribes like the Klickitats and Yakimas, trading marine products and intermarrying with them. They purchased horses from the Klickitats, pasturing them on their prairies, and raising more horses than most tribes west of the Cascades3.

- Geographical Distribution: Historically, the Nisqually occupied around forty villages on both banks of the Nisqually River, extending nearly thirty miles upstream from its delta. Today, tribal members live on the reservation in Thurston County or in the lower Nisqually valley, with some intermarrying with Puyallups, Muckleshoots, and members of other tribes3.

- Population Dynamics: The Nisqually tribe’s population fluctuated over time due to various factors like disease and historical events. In 1989, their tribal membership was listed at 1,455. By the time of the Medicine Creek Treaty in 1854, their population numbered less than 3003.

These relationships highlight the interconnectedness of indigenous tribes in the region and their shared histories of trade, cultural exchange, and geographical distribution.

The history of the Nisqually Delta is deeply intertwined with the Nisqually Tribe’s ancestral lands and environmental conservation efforts:

- Historical Significance: The Nisqually Delta has been a vital area for the Nisqually Tribe, who have lived in the region for thousands of years, fishing in the Nisqually River, building seasonal villages, and utilizing the estuary for shellfish harvesting3.

- European Influence: In 1830, the Hudson Bay Company established Fort Nisqually in the area, initiating European-style farming practices that impacted the land and its use3.

- Conservation Efforts: Over time, the Nisqually Delta faced challenges from industrial development proposals, including plans for a garbage dump and deepwater port. However, citizen groups like the Nisqually Delta Association and environmental activists fought to protect the delta from such developments5.

- Environmental Restoration: In more recent times, restoration efforts led by the Nisqually Tribe and other organizations have focused on removing agricultural dikes to flood parts of the delta, allowing for estuary restoration and habitat enhancement for wildlife like salmon and waterfowl3.

The Toliva Shoal Race, part of the Southern Sound Series, has been running since the early 1970s. The race was started by the South Sound Sailing Society in 1971, with the Olympia Yacht Club becoming a co-sponsor the following year. By 1974, the race had become an annual February event for the OYC, attracting more than 70 boats in recent years1. The Toliva Shoal Race typically attracts between 60-100 boats from throughout Puget Sound, making it the best-attended race in the series and a significant event in the sailing community4. Spectators can view the race from various vantage points, offering a unique perspective on sailing competitions amidst the natural beauty of the area.

- Route Description: The race typically begins and ends in Olympia, covering a course that takes sailors 38 miles out through Nisqually Reach before turning for home at Toliva Shoal. The return trip stays north of Anderson Island, offering participants a challenging and scenic sailing experience5.

- Historical Context: The Toliva Shoal Race has been an annual February event since the early 1970s, attracting more than 70 boats in recent years. It is the third race in the Southern Sound series, which includes races sponsored by Three Tree Point, Gig Harbor, and Tacoma Yacht Clubs2.

- Race Dynamics: Participants navigate through various points along the course, facing different wind conditions and challenges. The race traditionally involves strategic planning based on wind predictions and current patterns to optimize performance and complete the course successfully5.

The Toliva Shoal Race provides sailors with an exciting and competitive sailing experience along a well-established route that showcases the natural beauty of Nisqually.

The race passes near the Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge, providing a scenic backdrop for the event. In 2023, there were sporty conditions and a shortened course due to weather conditions4. It is possible to view the Toliva Shoal Race from the Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge, offering spectators a unique vantage point to enjoy the sailing competition amidst the natural beauty of the refuge.

The history of the Nisqually Delta reflects a complex interplay between human activities, conservation initiatives, and the enduring connection of the Nisqually Tribe to their ancestral lands.

Charles Wilkes’ expedition, known as the United States Exploring Expedition (1838-1842), had a significant impact on the Nisqually Delta and the broader Pacific Northwest region. While Wilkes did not specifically meet with the Nisqually Tribe, his exploration and mapping efforts contributed to expanding American influence and knowledge in the area:

- Exploration and Mapping: The expedition explored and mapped the Pacific, Antarctica, and the northwest coast of the United States, including Puget Sound and areas near the Nisqually Delta. Wilkes’ surveys of Admiralty Inlet and Hood Canal were among the first official U.S. hydrographical surveys of these waters5.

- Scientific Contributions: The expedition collected a vast amount of scientific data, including zoological specimens, plants, ethnographic artifacts, fossils, and more. This data significantly contributed to scientific knowledge and laid the foundation for future research in the region5.

- Political Implications: Wilkes’ expedition had political implications, influencing negotiations between the United States and Great Britain over territorial boundaries in the Pacific Northwest. The expedition’s findings increased American interest in the region and its potential for commerce and influence5.

Overall, Charles Wilkes’ expedition played a crucial role in exploring, mapping, and documenting the Pacific Northwest, including areas near the Nisqually Delta, shaping scientific understanding and political dynamics in the region.

The fort near the Nisqually River was established by the Hudson Bay Company in 1830. They built Fort Nisqually on a bluff where the city of DuPont is now located, initiating European-style farming in the area1.This establishment marked an early European presence in the region and impacted the Nisqually people’s land and way of life. Additionally, in 1917, Pierce County acquired 3,353 acres of Nisqually land for the Fort Lewis Military Reserve through condemnation proceedings, further affecting the tribe’s territory and relationship with the military2.

During Charles Wilkes’ exploration in the Pacific Northwest, specifically when the United States Exploring Expedition reached the Puget Sound area in 1841, the Nisqually people did indeed have horses.

Native American tribes, including those in the Pacific Northwest, were known to have horses that descended from those originally brought to the Americas by the Spanish. These horses were integral to the cultures of many tribes, used for transportation, trade, and warfare.

On July 5, 1841, during the first Fourth of July celebration held by the Wilkes Expedition in the Puget Sound region, the expedition crew enjoyed horse races on Indian horses1. This indicates that the Nisqually people and possibly other Native American groups in the region had horses that were significant enough to be part of celebratory events and interactions with the expedition members.

The horses present in the Pacific Northwest during Wilkes’ time were likely descended from those originally brought to the Americas by the Spanish and subsequently traded among Native American tribes. Over time, horses became integrated into the cultures and economies of many Native American tribes, including those in the Pacific Northwest. The mention of horse races during the Wilkes Expedition’s celebration suggests that horses were an established part of life for the Nisqually people and their neighbors by the early 19th century. Hence people of grass

Yes, the Nisqually people still engage with horses, although the specific activity of horse racing is not explicitly mentioned in the search results. The Nisqually Medicine River Ranch is involved in equine-assisted therapy and learning, utilizing horses as guides for therapeutic activities[2]. Additionally, historical accounts highlight the Nisqually Indians’ historical involvement with horses, showcasing a longstanding tradition within the tribe[5]. While horse racing is not directly addressed in the provided information, the Nisqually Tribe’s connection to horses remains evident through their equine-assisted therapy programs and historical ties to horse culture.

Sources

[1] Horseback Riding – Nisqually River Council https://nisquallyriver.org/watershed-services/recreation-opportunities/horseback-riding/

[2] Equine Assisted Therapy & Learning – Nisqually Indian Tribe http://www.nisqually-nsn.gov/index.php/administration/nisqually-medicine-river-ranch/equine-assisted-therapy-and-learning/

[3] Nisqually Tribe buys 200 acres surrounding Cabela’s from … – Reddit https://www.reddit.com/r/olympia/comments/me4l72/nisqually_tribe_buys_200_acres_surrounding/

[4] Nisqually Medicine River Ranch http://www.nisqually-nsn.gov/index.php/administration/nisqually-medicine-river-ranch/

[5] Woodbrook Hunt Club – Arcadia Publishing https://www.arcadiapublishing.com/products/9780738558639

50 Years Since Boldt Decision

In the shadow of Rainier, by the Nisqually’s flow,

Lived a people in peace, with the salmon’s glow.

For ten thousand years, a culture so grand,

Till the strangers came, to the Nisqually land.

From the Great Basin’s heart, ‘cross uthe mountains they came, Squalli-absch, the people, Nisqually their name. With nets cast in rivers, and horses that raced, Their life was the water, the land they embraced.

But treaties were signed, and the lands were confined, Chief Leschi resisted, his fate intertwined. The struggle ensued, a history of pain, For the land they had lost, and the rights they would gain.

Through the years of despair, the Nisqually stood strong, With the Boldt Decision, correcting a wrong.

Half the salmon, the ruling, a victory clear, For the tribes of the Sound, the waters they revere.

Now the largest employer, in Thurston, they rise, With casinos and commerce, under Washington skies. The elders look on, with a hopeful gaze, That the youth will remember, the traditional ways.

Language and fishing, the horses that run, The turn of the cards, where the rivers are one. May the children of Nisqually, with pride in their stride, Carry forward the legacy, with each rising tide.

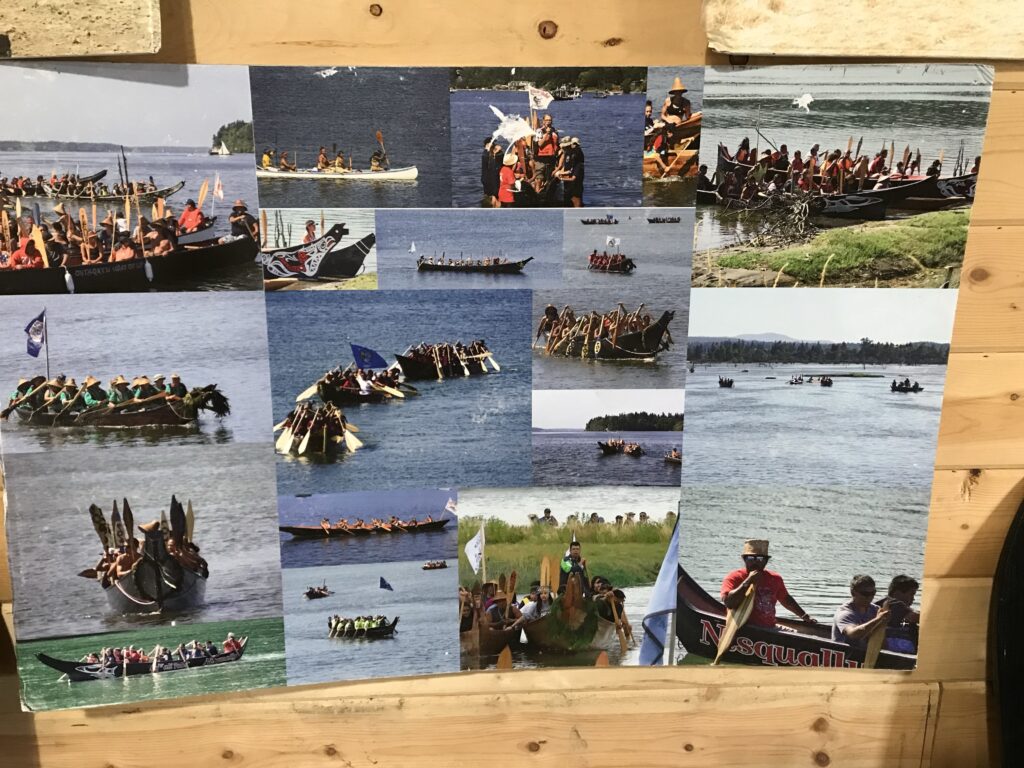

Journey of the Canoes

In the waters of Nisqually, where the currents dance and sway, The canoes glide in harmony, at the break of day. With paddles dipping softly, in the morning’s gentle light, The Nisqually people journey, with other tribes in sight.

From the Toliva Shoal, where the marine life thrives, Beneath the waves’ serene embrace, a sanctuary survives. The shoal, a hidden treasure, beneath the Puget’s blue, A testament to nature’s grace, and the respect that is due.

The Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge, by a new name proudly stands, A tribute to a leader bold, who walked these lands. Billy Frank Jr.’s legacy, in every bird’s flight, In every leaf and ripple, in the day and in the night.

But today, the canoes journey, with a message clear and true, Of unity and stewardship, and a respect that’s overdue. For the waters that sustain us, for the land that gives life, For the traditions of the Nisqually, in their beauty and their strife.

So let us honor these connections, in the stories that we tell, Of the canoes and the sailboats, and the waters where they dwell. For in each stroke and sail unfurled, a shared destiny we find, A journey of respect and love, for the water and mankind.

Nisqually tribal representatives have unveiled their plans for land the tribe owns near the outdoors store Cabela’s, and those plans include a 155,000-square-foot casino and a 350-room hotel.

In addition to the casino-resort, which the tribe is calling the Quiemuth Resort (pronounced kway-mooth), there’s also Quiemuth Village, a mixed-use development proposal.

The Nisquallys own the 250-acre parcel that surrounds Cabela’s. It is north of I-5, west of Marvin Road Northeast and south of Britton Parkway.

https://news.yahoo.com/nisquallys-unveil-sweeping-eye-opening-040912241.html