The Golden Age of Piracy, roughly spanning from the 1650s to the 1730s, was a period marked by a surge in maritime piracy in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. Some of the most notorious pirates of this era include:

- Henry Morgan: A Welsh privateer who raided Spanish settlements in the Caribbean, including the sack of Panama City in 1671. He was later knighted by the English crown for his exploits.1

- Henry Every: An English pirate who led one of the most profitable pirate raids of the era, capturing a fleet of Mughal ships in the Indian Ocean in 1695. He was one of the most successful and wealthy pirates of the Golden Age.1

- Blackbeard (Edward Teach): A fearsome English pirate who terrorized the Caribbean and the Atlantic coast of North America in the early 18th century. He was known for his distinctive appearance and brutal tactics.34

- Anne Bonny and Mary Read: Two female pirates who sailed with the infamous Captain “Calico Jack” Rackham in the Bahamas. They were known for their fierce fighting abilities.34

Many of the Golden Age pirates, such as Henry Morgan, started out as privateers – sailors authorized by governments to attack and loot enemy ships. The key difference is that privateers operated under a “letter of marque” granting them legal sanction, while pirates acted without such authorization and were considered criminals.23

The Golden Age of Piracy came to an end in the late 1720s as the major maritime powers, especially Britain, cracked down on piracy. Hundreds of pirates were captured and executed, and the appointment of Woodes Rogers as the first royal governor of the Bahamas in 1718 led to the expulsion of many pirates from their stronghold in Nassau.34

According to the search results, the main motivations for piracy during the Golden Age were:

- Lack of employment opportunities for sailors after the end of major conflicts like the War of the Spanish Succession. Many former privateers turned to piracy when they were left without work.25

- The opportunity for wealth and freedom that piracy offered, as described in this quote from an 18th-century Welsh pirate captain: “In an honest Service, there is thin Commons, low Wages, and hard Labour; in this, Plenty and Satiety, Pleasure and Ease, Liberty and Power…”3

- The abundance of valuable cargo being shipped by merchant vessels, combined with reduced naval presence in certain regions, making them easy targets for pirates.24

- Piracy being given legal status by colonial powers like France through the use of “letters of marque”, which sanctioned attacks on enemy ships and commerce.3

- The appeal of the “symbolic interpretation of freedom” that piracy offered, which was especially attractive to slaves and victims of imperialism.3

So in summary, the combination of lack of employment, the lure of wealth and freedom, favorable shipping conditions, and even legal sanction in some cases, all contributed to the motivations for the surge in piracy during the Golden Age.12345

Later an explorer named loánnis Fokás (Juan De Fuca) mapped out what he believed was the NW Passage and the Strait of Anián, what he discovered and mapped out eventually became known as the Straits of Juan De Fuca.

The actual strait connecting the Arctic with the Pacific was eventually discovered in 1728 and became known as the Bering Strait.

The most common methods used by pirates during the Golden Age of Piracy were:

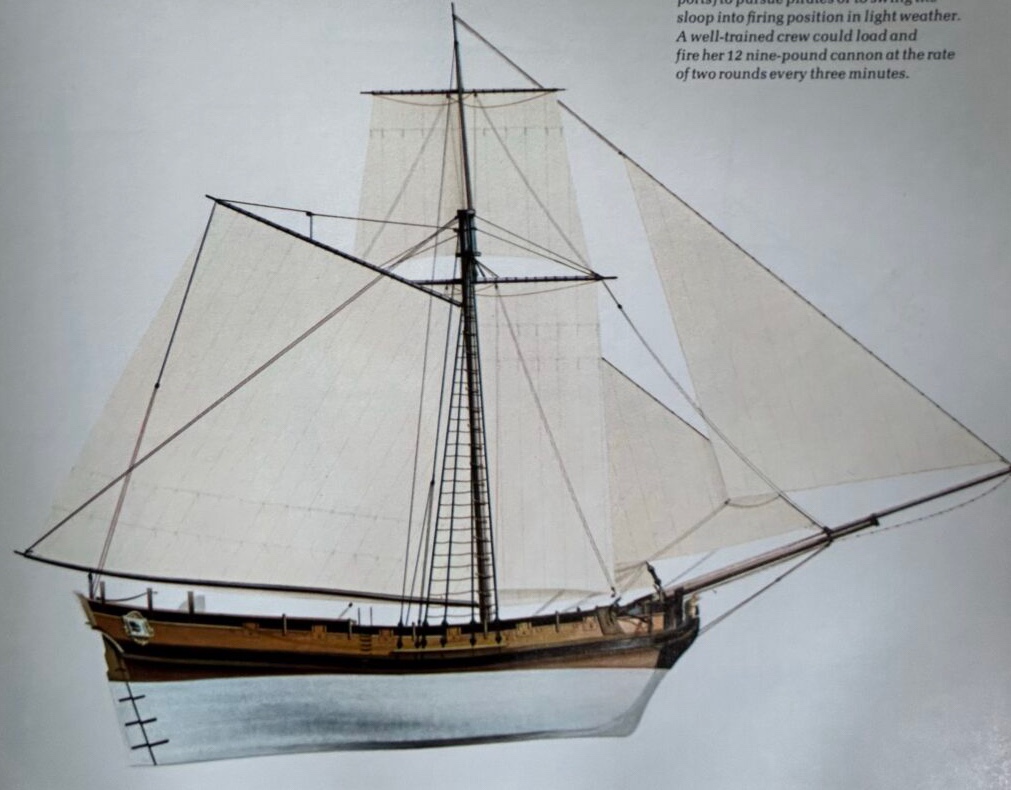

- Targeting merchant vessels: Pirates typically went after easy targets like merchant ships that were lightly armed, rather than heavily-armed naval vessels. They would often attack ships when they were in narrow straits or near shallows where the pirate ship could maneuver more easily.1

- Deception and disguise: Pirate ships would sometimes fly friendly national flags to get close to their target before revealing their true colors and attacking. They would also disguise their ships to appear as merchant vessels.1

- Overwhelming force: Some of the more successful pirates, like Blackbeard and Bartholomew Roberts, commanded large ships with crews of over 300 men and 40+ cannons, allowing them to overpower their targets.1

- Torture and cruelty: Many pirates, such as Edward Low and Bartholomew Roberts, were known for inflicting brutal punishments and tortures on their captives, including mutilation, forced starvation, and execution.23

- Marooning: For serious offenses against the pirate code, some pirates would maroon their own crew members on remote, uninhabited islands, leaving them to die.3

- Public executions: Captured pirates faced a high likelihood of being hanged, often in public displays meant to deter others from turning to piracy.24

So in summary, the Golden Age pirates relied on a combination of strategic targeting, deception, firepower, and sheer brutality to carry out their raids and maintain control over their crews and captives.1234

Pirates during the Golden Age of Piracy communicated with each other in a few key ways:

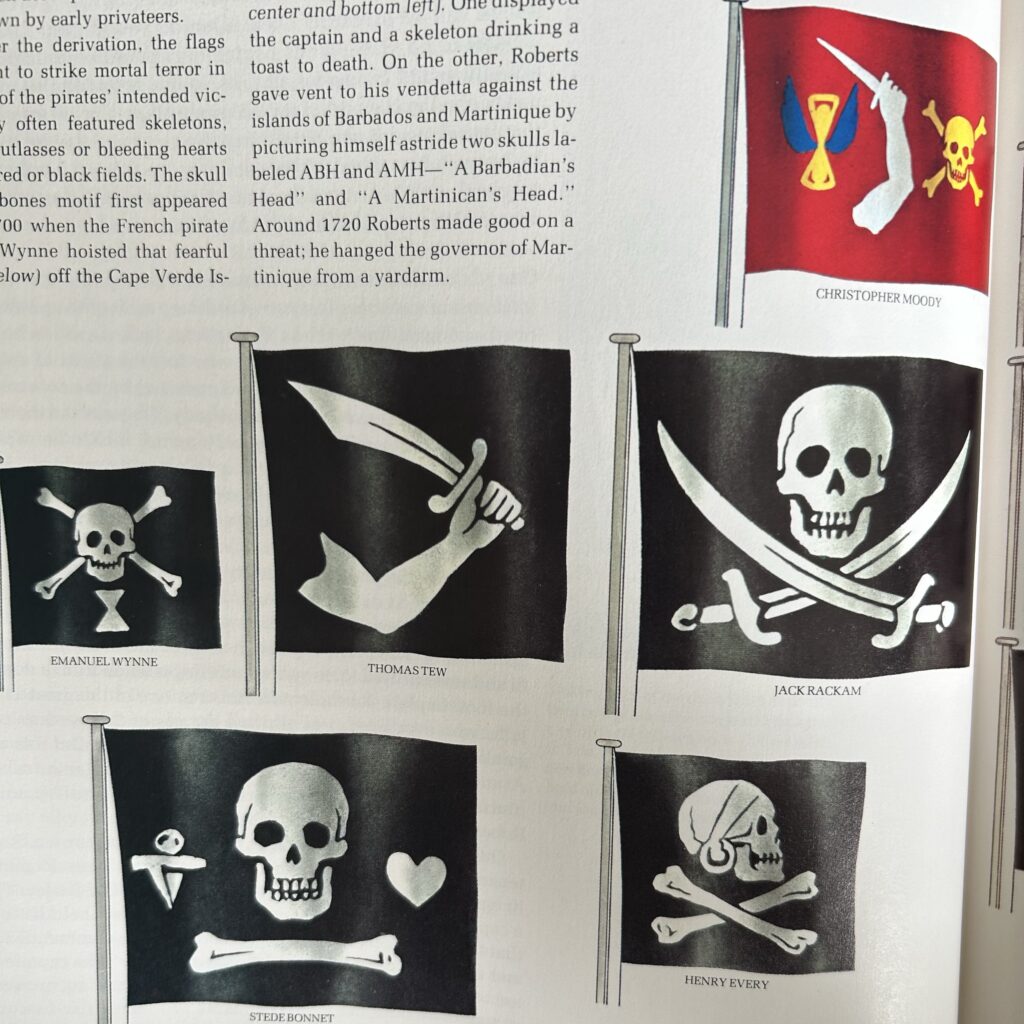

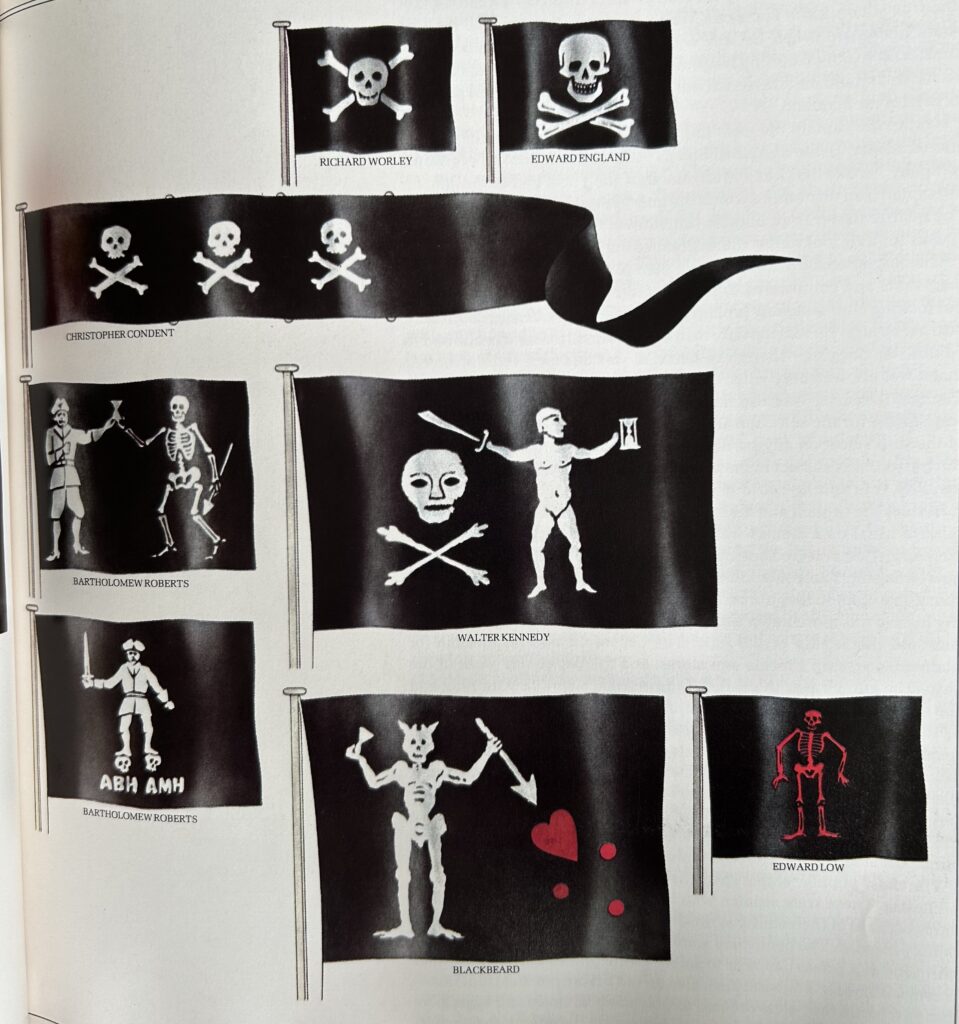

- The Jolly Roger flag: This distinctive black flag with a skull and crossbones was used by pirates to signal their identity and intentions to approaching ships. Hoisting the Jolly Roger was a way for pirates to communicate that they were about to attack and that the target ship should not resist.4 Historically it meant that those surrendering would not be killed.

- Signals and flags: Beyond the Jolly Roger, pirates used various other flags and signals to communicate with each other. This included using different colored flags to indicate whether they would offer quarter (a black flag) or not (a red flag).4 “No quarter” implies that captured enemies will not be spared, but will instead be killed. It means showing no mercy or pity to the enemy. 12 The term originates from the practice of not providing “quarter” or lodging/housing for captured enemy soldiers, and instead killing them. The red flag is also called the bloody flag.

- Shared language and culture: Many Golden Age pirates came from similar backgrounds, often being former sailors or privateers from Britain, France, the Netherlands, and other European nations. This allowed them to communicate effectively through a shared maritime vocabulary and cultural norms.15

- Pirate “nests” and hideouts: Pirates would often congregate in certain locations like Tortuga or Nassau, which served as hubs for communication, planning, and coordination of their activities.15

- Word of mouth: News and information about successful raids, new pirate captains, and other developments spread quickly through the informal networks and communities of pirates operating in the same regions.15

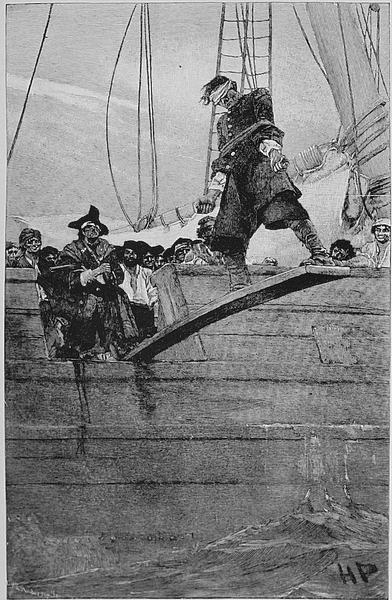

There is no recorded evidence of pirates forcing victims to walk the plank. This myth was brought around by famous writers such as Charles Ellms, Robert Louis Stevenson and Daniel Defoe in their efforts to bring a more dramatic flare to their epic tails of the high seas. Historically, pirates would either keel-haul victims, maroon them or simply throw them over the side. The famous portrait

depicted here was painted by Howard Pyle in 1887 for the Harper’s Magazine and helped to cement the legend forever in people’s minds.

So in summary, while pirates did not have modern communication technologies, they relied on a combination of visual signals, shared language and culture, physical meeting places, and informal information sharing to coordinate their activities and stay connected during the Golden Age of Piracy.145

Democracy not Autocracy

Pirates during the Golden Age of Piracy generally operated in a more democratic manner, rather than being ruled autocratically by a single captain:

- The search results indicate that “the majority of pirate ships elected their captains and leaders. Every member of the crew had an equal vote in who was going to lead them. And just as surprisingly, a leader could be voted out by the crew.” This democratic approach was in contrast to the hierarchical structure of merchant and naval ships at the time.

- The pirate “codes of conduct” that were commonly adopted, such as those of Captains Roberts, Phillips, Lowther, and Low, all emphasized the equality of the crew members. These codes stated that plunder would be shared equally, and that there would be equal voting rights.12

- The search results note that this democratic structure and equality among the crew was a key factor that attracted many sailors to join pirate ships, as it offered them more authority and a chance at greater wealth compared to the rigid hierarchies of merchant and naval vessels.12

So in summary, the evidence strongly suggests that pirates during the Golden Age operated in a relatively democratic manner, with captains being elected by the crew and having the potential to be voted out. This was a defining feature of pirate culture and governance during this period, in contrast to the autocratic leadership structures found on other maritime vessels.12

One of the first documented instances of piracy was in the Mediterranean in 1350 BC.

The Golden Age of piracy was considered between 1650 and 1720 AD.

The Jolly Roger was the traditional pirate flag depicted with a skull and crossbones.

Privateers were pirates commissioned by a government to hunt the enemy, especially during war. One of the most famous of these being Sir Francis Drake.

The most common reasons for a pirate captain to be voted out by the crew during the Golden Age of Piracy were:

- Cowardice in the face of the enemy: The search results indicate that the captain could be removed from their position if they showed cowardice during battle, as the crew valued bravery and leadership in combat.12

- Failing to capture enough prizes: If the captain was not successful in taking valuable prizes and providing enough plunder for the crew, they risked being voted out, as the crew’s primary motivation was the prospect of wealth.1

- Unfair treatment or distribution of loot: Captains who did not adhere to the democratic principles and equal distribution of spoils outlined in the “pirate codes” were vulnerable to being overthrown by their disgruntled crews.1

- Desertion or abandoning the crew: As seen in the case of Blackbeard, captains who tried to abscond with the loot and leave their crews behind were swiftly deposed.1

- Lack of leadership: More generally, captains who failed to effectively lead their crews or make sound decisions could be voted out if the crew lost confidence in their abilities.1

So in summary, pirate captains during the Golden Age were subject to being voted out by their crews primarily for reasons related to combat performance, economic success, adherence to the pirate code, and overall leadership – reflecting the democratic nature of pirate governance at the time.12

Blackbeard’s surname Teach, as long believed, was likely Thatch.

Blackbeard

Out of all the pirates who’ve trolled the seas over the past 3,000 years, Blackbeard is the most famous. His nearest rivals—Capt. William Kidd and Sir Henry Morgan—weren’t really pirates at all, but privateers, mercenaries given permission by their sovereign to attack enemy shipping in time of war. Blackbeard and his contemporaries in the early 18th-century Caribbean had nobody’s permission to do what they were doing; they were outlaws. But unlike the aristocrats who controlled the British, French and Spanish colonial empires, many ordinary people in Britain and British America saw Blackbeard and his fellow pirates as heroes, Robin Hood figures fighting a rear-guard action against a corrupt, unaccountable and increasingly tyrannical ruling class.

… Blackbeard was likely one of the first pirates to come to Nassau after the end of the War of Spanish Succession. He was probably one of the 75 men who followed the Jamaican privateer Benjamin Hornigold to the ruined town in the summer of 1713, and whose early exploits were documented by the governor of Bermuda and even received attention in the American colonies’ only newspaper, the Boston News-Letter. The war was over, but Hornigold’s gang continued attacking small Spanish trading vessels in the Florida Straits and isolated sugar plantations in eastern Cuba.

The Last Days of Blackbeard

Based on the information provided in the search results, it does not appear that Blackbeard’s crew members were sold back into slavery after he abandoned them:

Sir Francis Drake (1540-1596) was commissioned by Queen Elizabeth l as a privateer to attack spanish ships. a turning point in his career was the capture of the Portuguese merchant vessel, The Santa Maria, in 1578.

Sir Chaloner Ogle (1681-1750) was a Royal Navy officer who was known for his engagment and destruction of Bartholomew Robert’s fleet during the Battle of Cape Lopez in 1722. This was a major turning point in the struggle against piracy and many consider this the end of the Golden Age of Piracy.

Mary Read (Unknown-1721) often went by Mark Read and was known for constantly disguising herself as a man.

Colonel William Rhett (1666-1723) was famous for his capture of the pirate Stede Bonnet during the Battle of Cape Fear River in 1718.

“Black Sam” Bellamy (1689-1717) was recorded to be the wealthiest pirate in history, though his actual pirate career lasted less than two years. He was also nicknamed the Prince of Pirates and the Robin Hood of the Seas because of his generosity.

Lt. Robert Maynard (1684-1751) was famous for killing Edward “Blackbeard” Teach in 1718.

- The search results indicate that when Blackbeard intercepted the slave ship Concorde, he kept 157 of the African captives on board to serve as part of his pirate crew, either as free members or as forced labor.23

- However, the remaining 455 enslaved Africans on the Concorde were returned to the ship’s captain, who then used a small sloop to ferry them back to Martinique to be sold at auction.2

- There is no mention in the search results of Blackbeard selling or returning any of his own pirate crew members to slavery after abandoning them. The focus is on the fate of the enslaved Africans from the Concorde, not Blackbeard’s own crew.2

- The search results state that Blackbeard “bribed colonial governor Charles Eden to ignore criminal activities” in North Carolina, allowing Blackbeard to operate freely in the region. 1 He may have been interested in slaves as part of the bribes.

- When Blackbeard surrendered to Governor Eden, he was granted a pardon and “legal title to the sloop they’d arrived in.” This suggests the deal was focused on Blackbeard’s own activities and ships, not the trafficking of slaves. 3

- In fact, the search results suggest that many pirates, including those of African origin, saw service on pirate ships as a way to escape the life of plantation slavery.2

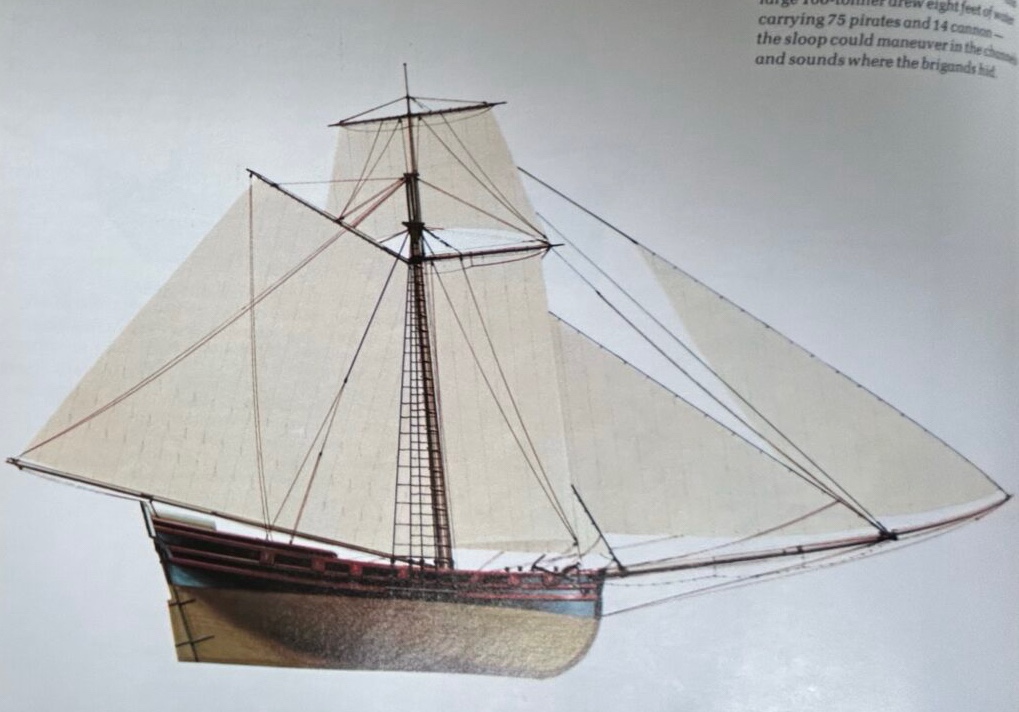

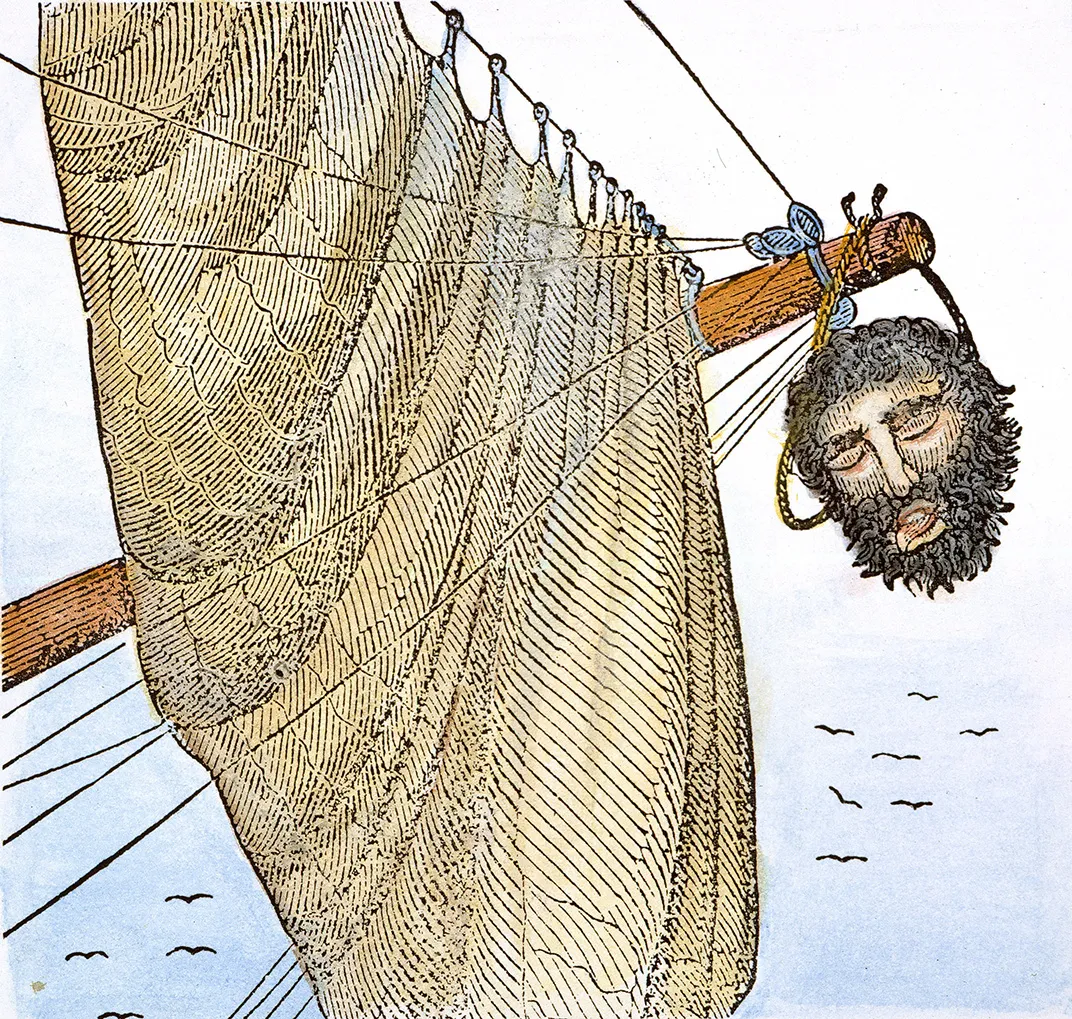

During Blackbeard’s career he commanded over three hundred pirates and had 14 wives. His head was displayed as a warning to his followers.

So in summary, the available information indicates that Blackbeard did not sell his own pirate crew members back into slavery when he abandoned them, but rather that he incorporated some enslaved Africans into his crew while returning the majority to be sold. The fate of his own crew members is not explicitly addressed in these search results.1234

Captain Kidd

Based on the search results provided, here is what I can tell you about Captain Kidd:

The word buccaneer derives from the French word Boucan and originally applied to hunters of wild boar and cattle around Hispaniola. The meat was cooked over slow fires located under small structures (Boucans) to make smoked meat. They sold the meat to the local corsairs and eventually the name Boucans or Buccaneers applied to the corsairs and then later to pirates in general. The word was also adopted by the spanish as barbacoa or the now familiar, barbacue.

- Captain William Kidd (also spelled “Kid”) was a Scottish sailor and privateer who was later accused of piracy. He commanded a ship called the “Adventure Gally” and was given a commission by the English crown to hunt down pirates.1 A gally is a ship that has oars for propulsion as well as sails.

- The search results indicate that Kidd was initially recommended by the Governor of Barbados and others to the English government to be entrusted with a ship to help combat the growing problem of piracy in the West Indies. However, this proposal was not taken up by the government at the time.1

- Frustrated by the lack of official support, a group led by the Earl of Bellomont then outfitted their own ship and gave Kidd the command, with a royal commission to attack pirates. This suggests Kidd was initially tasked with pursuing pirates, before later being accused of becoming one himself. He had a reputation as a brave and experienced seaman.2

- When Kidd failed to find any pirates to attack, he may have turned to piracy himself. In 1698, his ship the Adventure Galley ran aground in Madagascar, and his crew deserted him to join another pirate captain.1

- As for burying treasure, the search results mention a legend that in 1699, Kidd is said to have hidden $30,000 in treasure on Liberty Island, with the permission of the Gardiner family.

- More recently in 2015, archaeologists claimed to have discovered part of Kidd’s lost treasure – a 121-pound bar of silver – in a shipwreck off the coast of Madagascar, near where his ship had run aground.1

So in summary, the evidence indicates that Captain Kidd was initially tasked with pursuing pirates, before potentially turning to piracy himself when he failed to find any targets. There are also legends of him burying lost treasure, some of which may have been recently discovered, though the full truth remains elusive.12

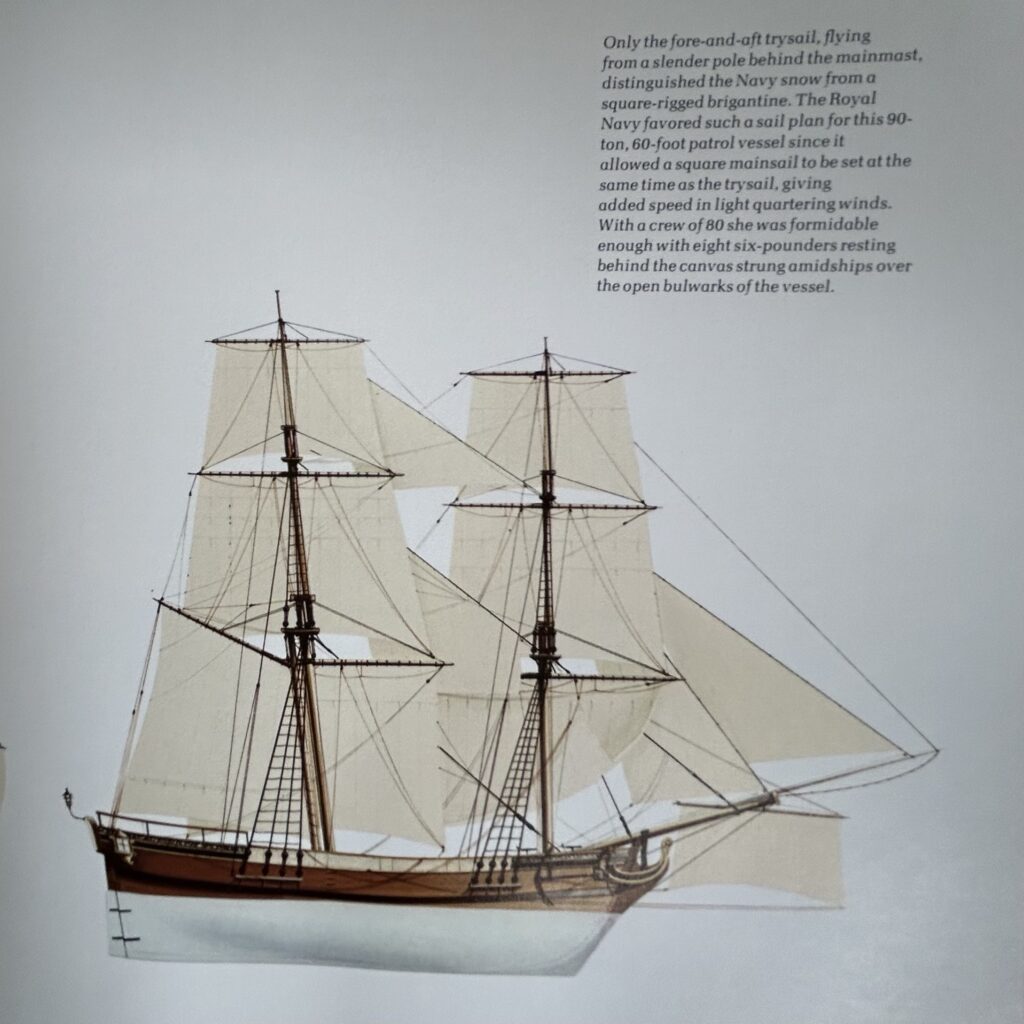

With a crew of 80 she was formidable enough with eight six-pounders resting behind the canvas strung amidships over the open bulwarks of the vessel.

Nassau and the Bahamas

Based on the information provided in the search results, here is how Nassau and the Bahamas became a stronghold for pirates, what a buccaneer is, and why Jamaica was one of the wealthiest communities during the Golden Age of Piracy:

With a crew of 80 she was formidable enough with eight six-pounders resting behind the canvas strung amidships over the open bulwarks of the vessel.

- Nassau and the Bahamas as a Pirate Stronghold:

- The search results state that New Providence in the Bahamas, with its main city of Nassau, became a major pirate haven from the 1670s onward. 1

- It provided safe harbors, freshwater, food, and was close to major shipping routes, making it an ideal base for pirates. 134

- Corrupt governors like Charles Eden in North Carolina turned a blind eye to pirate activities, allowing them to operate freely from Nassau. 1

- By the early 18th century, there were around 600 pirates sailing from Nassau, raiding shipping and ports across the Caribbean and up the Atlantic coast. 1

- What is a Buccaneer?

- The search results explain that buccaneers were former slaves and French settlers who established themselves on the island of Tortuga in the early 1600s. 4

- They were known for a cooking method called “boucaner” and dubbed themselves the “Brethren of the Coast”. 4

- From Tortuga, the buccaneers launched raids on Spanish settlements in the Caribbean, before being expelled by the Spanish in 1654. 4

- Jamaica as a Wealthy Pirate Haven:

- Port Royal, Jamaica became one of the largest pirate havens during the Golden Age, from the 1650s to 1680s. 4

- It earned a reputation as the “wickedest city in the world”, with brothels, taverns, and countless pirates spending their ill-gotten gains. 4

- The British and French governments even issued letters of marque to privateers operating out of Port Royal, sanctioning attacks on Spanish shipping. 4

- Port Royal was considered one of the wealthiest communities in the world at the time due to the influx of plundered riches from the pirates and privateers based there. 4

In summary, Nassau in the Bahamas and Port Royal in Jamaica were two of the most notorious pirate strongholds during the Golden Age, providing safe havens, corrupt governance, and access to lucrative shipping routes that allowed piracy to thrive. Buccaneers, like those based in Tortuga, were a key part of this pirate culture in the Caribbean.

Here is a poem about the Golden Age of Pirates and the Bahamas, including references to Jamaica, Blackbeard, and the themes of fighting autocracy and fostering rule by the many:

The Golden Age of Pirates

In the Bahamas’ azure seas,

A haven for the boldfaced and free,

Nassau, a pirate’s paradise,

Where Blackbeard’s shadow cast its vice.

From Jamaica’s shores, the plunder flowed,

Riches that the wicked hoard,

A testament to piracy’s might,

Defying autocratic blight.

On the high seas, they ruled the waves,

Captains and crews, no masters to crave,

A democracy of the daring and bold,

Wealth and freedom, their tales untold.

Yet, the tides of change, they ebb and flow,

As modern times, new battles sow,

The fight against autocracy’s hold,

A struggle for the many, not the old.

In Nassau’s streets, the echoes remain,

Of a time when pirates broke the chain,

A lesson in the power of the many,

To challenge the few, and claim their destiny.

So let the Jolly Roger fly,

A symbol of the spirit that won’t die,

As we strive for a world more fair and just,

Where the rule of the many, we can trust.

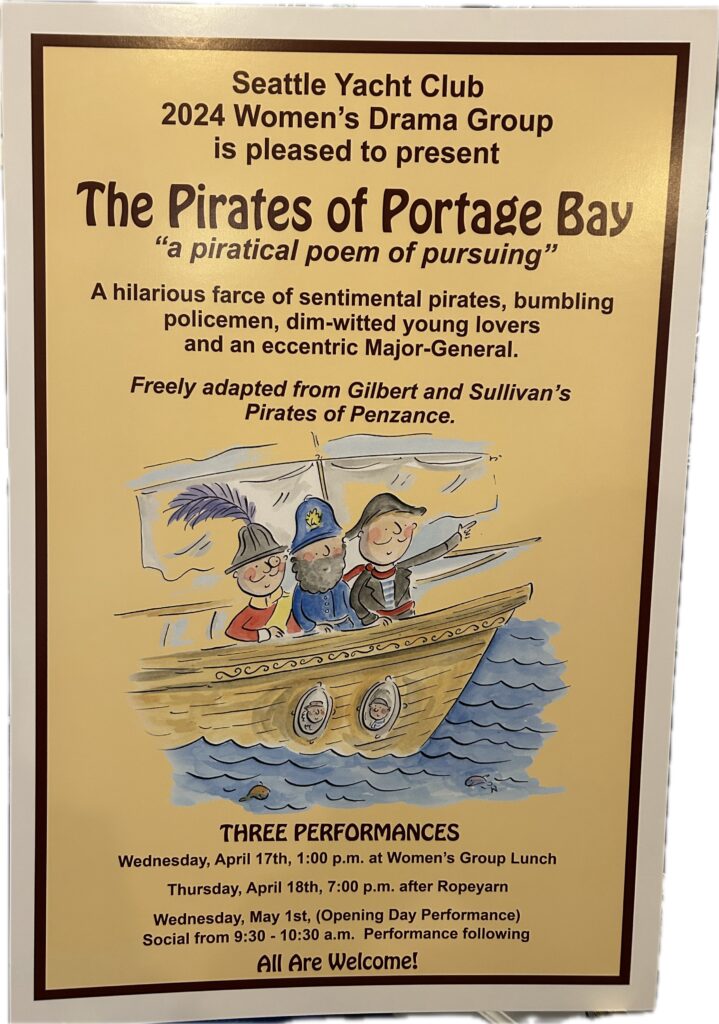

Pirates of Portage Bay

The year was 1718, and the Golden Age of Piracy was in full swing. Portage Bay, a small coastal town in the Caribbean, was a hub of pirate activity. Among the many pirates operating in the area was a young man named Jack, who had been an apprentice to the infamous pirate, Blackbeard.

Jack’s story began when he was just a boy, living in the streets of Portage Bay. He had no memory of his parents and was forced to survive on his own. He eventually apprenticed with pirates and became a skilled sailor. When he turned 21, he decided to leave the pirate life, hoping to find a sense of belonging and honest adventure.

As Jack’s reputation grew, so did his love for a young woman named Emily, the daughter of a major general. Emily was beautiful, kind, and had a heart of gold. She and Jack had met while he was still an apprentice, and their love had blossomed over the years.

However, their love was forbidden. Emily’s father, the major general, was a powerful man who did not approve of Jack’s pirate lifestyle. He saw Jack as a common thief and a menace to society. When Jack was captured by the British Navy, Emily’s father saw an opportunity to use Jack’s capture to his advantage.

Jack, desperate to be released from captivity, claimed to be an orphan. He told the British that he had no family and was alone in the world. Emily’s father, believing Jack’s story, agreed to release him and his daughters from captivity if Jack would agree to marry one of them.

Jack, knowing that he had no choice, agreed to the proposal. He was released from captivity and married Emily’s sister, Sarah. However, Jack’s love for Emily never faded, and he continued to see her in secret.

As the years passed, Jack’s pirate days were numbered. He had reached the end of his apprenticeship, and it was time for him to go legitimate. Unfortunately, his plan was based on birthdays, and he was born on February 29th, a leap day. He had always known that he would have to wait four years to celebrate his birthday, but he had never thought about the implications of being a pirate on a leap day.

When Jack turned 25, his pirate band returned to their noble roots. As noble men the could start a new life. Jack and Emily were finally able to be together, and they were married in a beautiful ceremony. Jack’s daughters from his previous marriage were also present, and they were happy to see their father happy.

As the years passed, Jack and Emily built a life together. They had children and grandchildren, and Jack became a respected member of society. He never forgot his pirate days, but he was grateful for the opportunity to start anew.

In the end, Jack and Emily’s love story was one of true devotion and perseverance. They had faced many challenges, but their love had always prevailed. And as they looked out at the sea, they knew that their love would last forever.

Major-General’s Song

I am the very model of a modern Major-General. I’ve information, vegetable, animal and mineral; I know the Kings of England, and I quote the fights historical from Marathon to Waterloo in order categorical; I’m very well acquainted too with matters mathematical, I understand equations, but the simple and quadratical, about binomial theorem I’m teeming with a lot of news – with many cheerful facts about the square of the hypotenuse.

I’m very good at integral and differential calculus, I know the scientific names of beings animalculous; in short, in matter vegetable, animal and mineral, I am the very model of a modern Major-General.

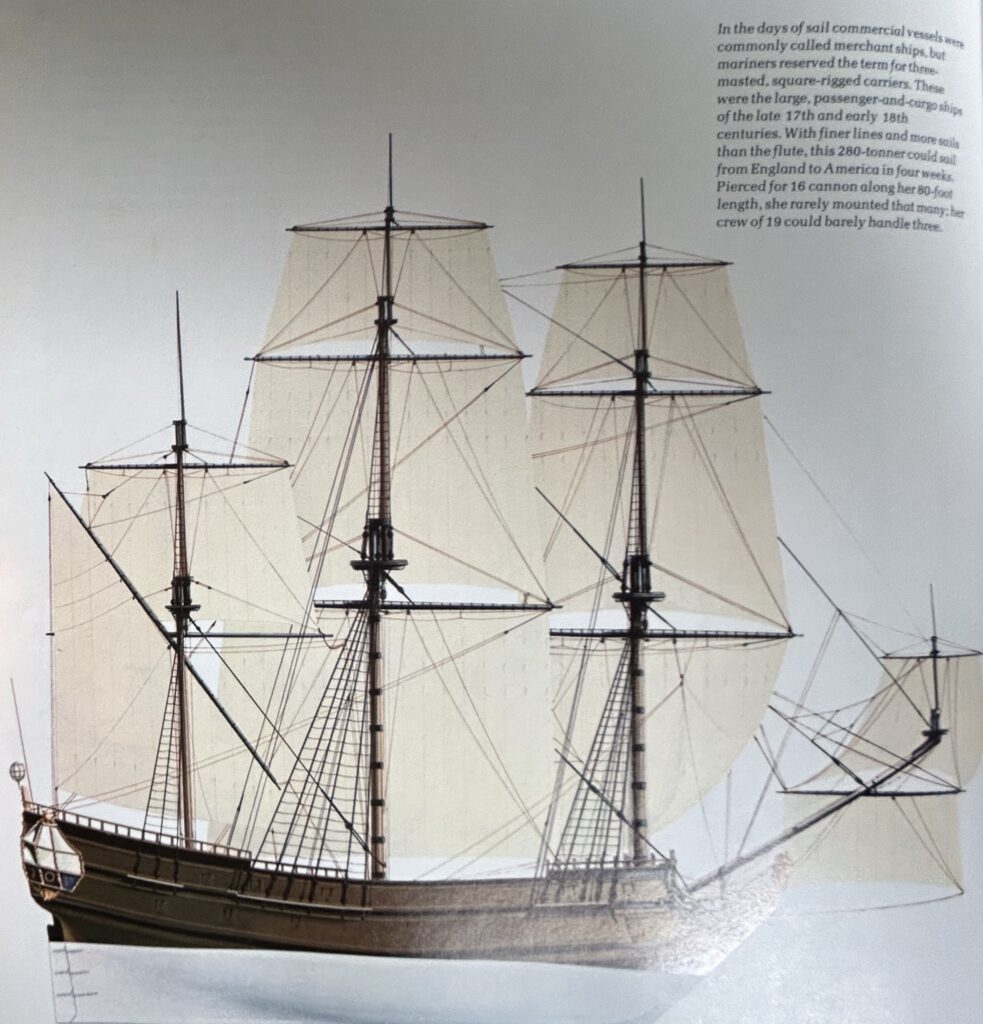

Round-sterned, broad-beamed and flat-bottomed, the Dutch flute made her debut in the early 17th Century. The flute was inexpensive to build, cheap to man (only 12 in crew for this 80-foot 300-tonner) and renowned for her cargo capacity – half again that of similarly sized vessels with sleeker lines. The English and French quickly adapted the design, and flutes ranged the world’s sea-lanes where they became routine prey for pirates.

For my military knowledge, though I’m plucky and adventury, has only been brought down to the beginning of the century; but still in matters vegetable, animal and mineral, I am the very model of a modern Major-General.

Music by Arthur Sullivan Libretto by W.S. Gilbert

Pirate and Privateer Ships

Here is the list of pirates and privateers mentioned in the search results:

- Blackbeard (Edward Teach)

- Boat Type: Warship

- Years of Operation: 1717-1718

- Boat Name: Queen Anne’s Revenge

- Prizes Taken: Captured numerous ships; the most notable being the French slave ship La Concorde, which he refitted and renamed.

- Captain William Kidd

- Boat Type: galley ship

- Years of Operation: Late 1690s

- Boat Name: Adventure Galley

- Prizes Taken: Captured several ships during his privateering and alleged piracy career, though specific details of prizes are not listed in the search results.

- George Lowther

- Boat Type: Man of War (initially), later a pirate ship

- Years of Operation: Early 1720s

- Boat Name: Delivery (originally Gambia Castle)

- Prizes Taken: Engaged in piracy after mutinying and taking over the Gambia Castle; specific prizes not detailed in the search results.

- Bartholomew “Black Bart” Roberts

- Boat Type: Unknown

- Years of Operation: 1713-1722

- Boat Name: Royal Rover

- Prizes Taken: Captured and looted hundreds of ships over a three-year period.

- Henry Avery

- Boat Type: Dutch Frigate

- Years of Operation: 1694-1695

- Boat Name: Fancy (originally Charles II)

- Prizes Taken: Captured the Ganj-i-Sawai, the treasure ship of the Grand Moghul of India, in July 1695. C

- Woodes Rogers

- Boat Type: frigate from British East India Company

- Years of Operation: 1712

- Boat Name: Duke

- Prizes Taken: Rogers commanded a ship called the Duke, which was part of a larger expedition that also included the ship Duchess. The Duke is described as a “well-armed ship” and one of the “seven tall ships” that Rogers used to blockade Nassau where pirates were forced to accept pardon terms, or the gallows.

- Privateers (General)

- Boat Type: Various small vessels, typically schooners or sloops

- Years of Operation: 1775-1815 (American Revolution and War of 1812)

- Boat Names: Multiple, including Active, Lively, Enterprize, Hazard, Defiance, Hope, Dolphin, Union, Fame, Betsey, Sally, Nancy, Eliza, William, Friendship, and Ann.

- Anne Bonny

- Boat Type: Unknown

- Years of Operation: 1715-1720

- Boat Name: None mentioned

- Prizes Taken: Participated in several pirate attacks, including the capture of the Concorde.

- Mary Read

- Boat Type: Unknown

- Years of Operation: 1715-1720

- Boat Name: None mentioned

- Prizes Taken: Participated in several pirate attacks, including the capture of the Concorde.

- John Taylor aka Richard Taylor

- Boat Type: crewed on trading sloop Buck, then Victory, later elected Captain.

- Years of Operation: 1721

- Boat Name: None mentioned

- Prizes Taken: with La Bouche captured the Nostra Senhora, a Portuguese treasure ship.

- Olivier La Bouche

- Boat Type: Unknown

- Years of Operation: 1721

- Boat Name: None mentioned

- Prizes Taken: with Taylor captured Nostra Senhora, a Portuguese treasure ship.

- Bartholomew Roberts

- Boat Type: French Warship (26 guns)

- Years of Operation: 1713-1722

- Boat Name: Royal Fortune (Bartholomew Roberts commanded a succession of ships during his piracy career, including the “Royal Rover”, “Fortune”, “Royal Fortune”, and “Good Fortune”)

- Prizes Taken: Captured and looted hundreds of ships over a three-year period. Roberts was killed in battle with the British Royal Navy warship HMS Swallow, while sailing the Royal Fortune off the coast of Africa.

- Edward England an Irish Pirate

- Boat Type: Dutch frigate (34 guns)

- Years of Operation: 1720

- Boat Name: Fancy (originally Charles II)

- Prizes Taken: Captured a fine ship off Madagascar in 1720, which he renamed the Fancy. Captain England’s successful but brief pirate career came to an end when he was marooned by his crew on the island of Mauritius in 1720.

- Henry Morgan

- Boat Type: frigate warship

- Years of Operation: 1650s

- Boat Name: Satisfaction

- Prizes Taken: Engaged in privateering and piracy during the Spanish Succession War.

- Jean Fleury a French Pirate

- Boat Type: Jean Fleury was a Corsair naval officer

- Years of Operation: 1523

- Boat Name: None mentioned

- Prizes Taken: Raided Hernan Cortes’ ships in 1523 and recovered an ancient and valuable Aztec treasure. while the exact name and type of Fleury’s primary ship is not specified, the search results suggest he commanded a small squadron or fleet of vessels as a French corsair and privateer, rather than a single named ship.

- Francis Drake

- Boat Type: galleon

- Years of Operation: 1573

- Boat Name: None mentioned

- Prizes Taken: Captured the Spanish Silver Train in 1573 at Nombre de Dios in Panama.

- Stede Bonnet

- Boat Type: Unknown

- Years of Operation: 1717

- Boat Name: Whydah Gally

- Prizes Taken: Lost in a storm off Cape Cod in 1717.

- Every (Unknown)

- Boat Type: Unknown

- Years of Operation: Late 17th century

- Boat Name: None mentioned

- Prizes Taken: Evaded capture and the rest of his life is a complete mystery.

These entries provide a snapshot of the types of vessels used by pirates and privateers, their operational periods, the names of their ships, and the nature of their prizes. The data reflects the diverse and often dramatic careers of these maritime adventurers during the height of their activities.

A captain (me) salutes while all sing ‘A Pirates Life For Me’ with a hostage (Admiral Dave) in a cage before the mast. Treasure chests and cursed skeleton pirates with a dog are on deck.