Sir Thomas Lipton, the founder of the Lipton tea brand, was a self-made man, merchant, and yachtsman. Despite his business success and reputation, he was initially denied membership to the Royal Yacht Squadron, the prestigious sailing club that defended and lost the first America’s Cup challenge in 18517. This was possibly due to the fact that Lipton was seen as a commoner in the eyes of Britain’s aristocracy7.

Sir Thomas Johnstone Lipton, a Scottish merchant, was knighted in 1898 by Queen Victoria for his exceptional contribution to business3. He was later created a baronet in 19022. Lipton’s success in the tea industry, his philanthropic efforts, and his role as a yachtsman contributed to his recognition and honors24. Prior to starting his tea business, Lipton resided in the United States, where he worked as a laborer on tobacco and rice plantations and as a bookkeeper in a prosperous New York store1. During his time in the US, he absorbed American techniques of salesmanship, advertising, and management, which became his trademark1.

Lipton’s experience in the US influenced his retail techniques in his European enterprise. He recognized the need in England for reliably good tea and applied the American principles of salesmanship, advertising, and management to his business5. Lipton’s success was attributed to his ability to create an appealing shopping experience, display his goods with flair, and provide high-quality products5. He also implemented control over supply, sourcing his tea from Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and distributing it through Europe and the US24.

However, his persistent challenges to the America’s Cup through the Royal Ulster Yacht Club, and his well-publicized efforts to win the cup, eventually earned him entry into the Royal Yacht Squadron on the day of his 83rd birthday17. He died that same year.

Lipton’s interest in sailing began at a young age, and he was known for his passion for the sport and his sportsmanship. He presented a series of trophies, known as “Lipton Cups,” to different clubs between 1905 and 1930, including the New York Yacht Club, San Diego Yacht Club, Houston Yacht Club, Table Bay Yacht Club, and the Seattle Yacht Club among others9. These trophies were intended to promote the sport of yachting and his tea brand around the world. The story of Seattle’s Lipton Cup is noteworthy.

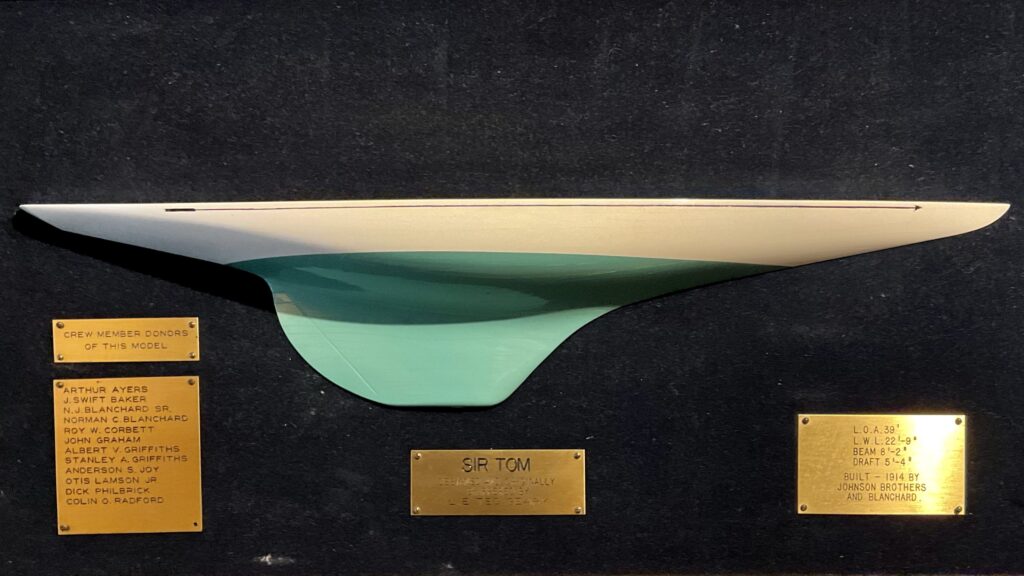

Sir Thomas commissioned the cup, which arrived in 1913 and was first contested in 1914 by the “R” boats “Sir Tom” of Seattle YC and “Turenga” of Royal Vancouver YC, Canada. With the demise of the “R” class, the Lipton Cup became the main trophy for the International 6 Metre Class in the Northwest post WWII. Winners of the Cup, including boat name, skipper, and crew, have been inscribed on the Cup or on small plaques encircling the base, for the past 100+ years.

The Seattle Times on April 18, 1909 published an

article centered on the upcoming Alexandra Cup international sailing regatta, it was mentioned in passing that “The consolidation of the Seattle Yacht Club and the Elliott Bay Yacht Club has not been effected, but this will be done before the preliminary race of June 12” (“Spirit II. and Rival Will Race”).

….

a primary stimulus for the consolidation was the desire to present a united front and joint resources to contest the Alexandra Cup, an annual race between American and Canadian sailing yachts that had been first run in 1907.

The Americans won that inaugural race and the Canadians won the 1908 contest, setting up a highly anticipated rubber match. In 1909 the American entry, supported by the new Seattle Yacht Club, won the first two races of the series. Then a rancorous dispute arose over the technical qualifications and official measurement of the Seattle boat, Spirit II, designed and skippered by the legendary Ted Geary (1885-1960), who had been vice-commodore of the Elliott Bay Yacht Club before the merger. In protest, the Royal Vancouver Yacht Club’s entry refused to finish the competition, and the club refused to turn over the Alexandra trophy to the Seattle organization.

….

With the unpleasant dispute over the Alexandra Cup in mind, Lipton announced that he would establish “a perpetual challenge cup for international yachting competition, to be raced for the first time in Seattle” (“Admirers in Seattle Pay Honor to Lipton”). Two years later, in July 1914, the Seattle Yacht Club became the first to have its plaque placed on the base of the Sir Thomas Lipton Perpetual Challenge trophy when Sir Tom, designed and skippered by Ted Geary, named in honor of Lipton, and sailing under Seattle Yacht Club colors, won the inaugural race on Elliott Bay by beating Turenga, a Canadian boat. Sir Tom would go on to win 14 consecutive Lipton Cup races and many other competitions, and Geary would earn legendary status in international “R-Boat” racing.

Seattle Yacht Club

In addition to the Royal Yacht Squadron, Sir Thomas Lipton was also a member of the Royal Cork Yacht Club, the oldest yacht club in the world2. The Royal Yacht Squadron, which was founded in 1815, started Cowes Week, one of the oldest and most respected regattas in the world3.

This connection between Lipton, the Royal Yacht Squadron, Seattle Yacht Club and Cowes Week highlights the significant influence Lipton had on the sport of sailing and his commitment to promoting it globally.

Seattle’s Lipton Challenge Cup

As mentioned, Ted Geary was part of a rancorous dispute that arose over the technical qualifications and official measurement of the Seattle boat, Spirit II, designed and skippered by Ted Geary, who had been vice-commodore of the Elliott Bay Yacht Club before the merger.

SPIRIT II

48′ x 28′ with 1,275-ft of sail.

Built by Adolph Rohlfs and Merrill at their new plant on the East Waterway. Photo dated, 8 June 1909. Seattle, WA.

Photographer unknown.

Photo from the Carl Weber Collection, S.P.H.S.© archives.

To finish the story about the dispute, the Alexandra Cup was not put at stake again for an astounding 99 years. When it finally was, in 2008, the Vancouver club retained the title and the trophy.

See Sailing: Alexandra Cup revival a Canadian win

SPIRIT II, 1909

Ted Geary, 1885-1960 (center) designer, helmsman

with Dean and Lloyd Johnson

ready for launching, Seattle, WA.

Photographer unknown.

From the Carl Weber Collection, S.P.H.S.©

SPIRIT II

Dated 29 June 1909

Seattle, WA.

Photographer unknown .

Carl Weber Collection, S.P.H.S. ©

Geary’s success in designing and racing boats, such as the Spirits, attracted the attention of several prominent Seattle businessmen who financed his education as a naval architect at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology1. Around 1907, Geary left Seattle to study naval architecture at MIT. He returned to Seattle in 1910 with a degree in naval architecture and soon had many commissions for yachts as well as work boats.

Ted went to high school at the old Broadway High on Capitol Hill, and I think he was probably designing boats even before he graduated in 1904. After he finished high school he enrolled at the U of WA, and in 1907, joined the Seattle Yacht Club when it was still known as the Elliott Bay Yacht Club.

The first yacht design that really brought Ted any acclaim was for the SPIRIT, launched in 1907. SPIRIT II was launched two years later. Ted designed her while still at the university, and she was built mostly by the Johnson brothers in a former firehouse on the top of Queen Anne Hill. A fire station bay in those days was about the right size to build a fairly good-sized boat. The SPIRIT was a 42-ft sloop, built to challenge the Canadians for the Dunsmuir Cup, and, skippered by Geary, she beat the Vancouverites entry, the ALEXANDRA, and won the cup from the Canadians in 1907.

The next year, the SPIRIT lost to the ALEXANDRA, so the SYC commissioned the SPIRIT II in 1909. Well, this second design was to the then-new Universal Rule, developed by Nathanael Herreshoff. And what Geary did was design the SPIRIT II with a keel that went from nothing and then was not totally straight down, but steeper than most. Practically all the English keel designs, like the Canadians’ ALEXANDRA, were the long, sweeping profile. So the SPIRIT II beat the Canadians the next season.In fact, I heard that they got so badly beaten that the measurer demanded that the SPIRIT II be hauled out so he could measure it, and he called this slight variation in design a notch in the keel. The first measurement was made in the notch. Of course, it wasn’t a notch at all, it was just kind of a corner. There’ve been thousands, tens of thousands, of boats built like this since. But this episode caused a rift between the Canadians and the Americans that was not patched up until 1912 when Sir Thomas Lipton visited Seattle and brought about a truce.

VESSELS SPIRIT, SIR TOM, and the GENIUS OF DESIGNER/SAILOR TED GEARY

Around 1907, Geary left Seattle to study naval architecture at MIT. He returned to Seattle in 1910 with a degree in naval architecture and soon had many commissions for yachts as well as work boats.

Ted Geary could make a sailboat sail faster than anybody else. He was probably the savviest helmsman on the west coast. He could sense changes in wind, things like that, with incredible accuracy. So for a good ten or eleven years, the SIR TOM was never beaten.

Leslie Edward “Ted” Geary became a renowned naval architect who grew up in Seattle. He was known for his designs of competitive sailing vessels, including the Sir Tom, an “R” class boat that dominated the racing circuit along the West Coast for three decades.

In 1920, J.W. Isherwood, a naval architect of London, England, contacted designer Alfred Green of the Joseph Mayer Jewlers Company of Seattle, WA to create one of the finest silver cups in the world. The entire cup is made of solid silver and at the time cost a staggering $3,000 (over $45,000 today) and weighs 100 Troy ounces. Isherwood, the inventor of the famous Isherwood system of longitudinal ship construction, announced that he would offer a cup that would exceed in value and beauty of the Lipton trophies. The Cup was presented to the Pacific International Yachting Association and was awarded for the Pacific Coast Championship for “Class R” Sailing Boats. The first race was held on September 3rd, 4th, and 5th, 1921, in Vancouver, B.C., and was awarded to the first R-boat to take three out of five consecutive-day races. The winner was Sir Tom, under the command of Ted Geary, SYC Seattle, who dominated R Class racing during the 1920s. It has not been awarded for many years because the R class boats no longer race and it has been officially retired.

In April 1914, the newspapers touted the first Lipton Challenge Cup Race, scheduled as part of Seattle’s Potlatch celebration.

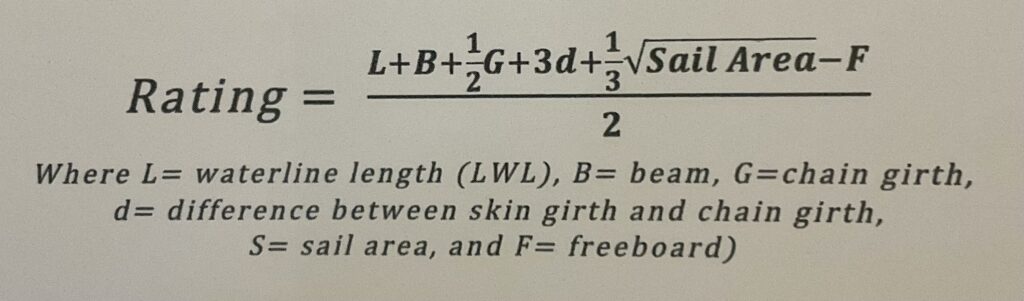

This regatta used the new R Boat, devised according to the Universal Rule, rather than 29 raters under the International Rule. Classes under the Universal Rule were designated by alphabetical letters. Each class corresponded to a range of permissible numerical ratings. A yacht’s rating (calculated by the Universal Rule’s mathematical formula) could not exceed the upper limit defined for the class in which she was to race. Several clubs had promised to send competitors, but most dropped out prior to July.

Seattle Yacht Club By John Caldbick

The Sir Tom was so impressive that it won both the Sir Thomas Lipton Cup and the Isherwood Cup in the, at the Victoria regatta. This led to yachtsman Don Lee ordering a custom R-boat design from Geary8. And Ed Monk crafting a half model of Sir Tom.

George Edwin William Monk, also known as Ed Monk, Sr. (1894-1973), was a shipwright and naval architect in the Pacific Northwest of the United States. He designed pleasure and commercial vessels, both power and sail. Monk began his boat building career in 1914 and was active until 1973.

Monk worked at various boatyards in Seattle and eventually found his way to the Blanchard Boat Co.

In 1925. At Blanchard Boat Co., Monk got to know Geary and in 1926, Geary hired Monk as a draftsman. In 1930, Monk followed Geary to Long Beach, CA. In 1933, Monk quit working directly for Geary and moved back to Washington state, but maintained his association with Geary3.

Monk designed both pleasure and commercial vessels, including power and sail boats3. Noted for power boats, he did design racing vessels. One notable example is the 66-foot racing yacht named Spirit, which was built by Harold A. Jones of Vancouver Tug in 19481.

In summary, Ted Geary was a prominent naval architect who designed the successful racing vessel Sir Tom. He also mentored Edwin Monk, another notable naval architect. Both had significant impacts on the sailing and boat-building scene in the Pacific Northwest, and their work is tied to the Seattle Yacht Club Lipton Challenge Cup through the success of the Sir Tom.

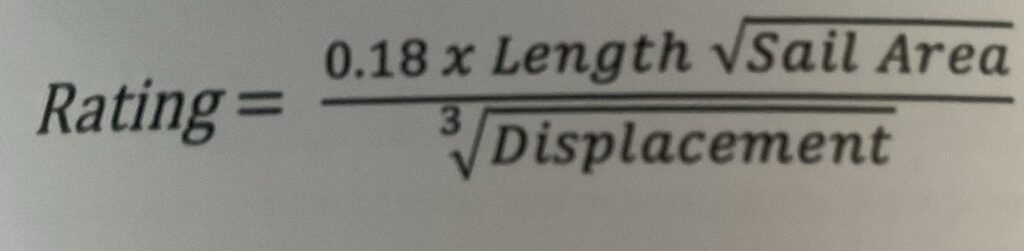

The Universal Rule and the International Rule are both rating systems used to classify sailing yachts of different designs to enable them to compete on relatively equal terms.

Universal Rule and the International Rule

The Universal Rule was introduced in 1903 by yacht designer Nathanael Herreshoff and was adopted by the New York Yacht Club. It was used to determine a yacht’s eligibility to race in the America’s Cup from 1914 to 1937, and the J-class was chosen for this purpose. The Universal Rule formula is as follows:

R = 0.18 * L * \sqrt{SA}/ \sqrt[3]{D}

Where:

- R is the rating

- L is the rated boat length

- SA is the sail area

- D is the displacement[1][7][10]

The International Rule, also known as the Metre Rule, was created for the measuring and rating of yachts to allow different designs of yacht to race together under a handicap system. It was ratified in 1907, and unlike the Universal Rule, it does not restrict size—many individual classes were created. It allowed designers a degree of latitude—yet controlled unsafe extremes. It laid down construction rules and governed the use of materials[3][5].

The two rules differ in their approach to yacht design. The Universal Rule tends to produce a boat with more balance, while the International Rule tends to produce a boat that is finer forward than aft[4]. The Universal Rule also made the rating go up as displacement went down, putting a limit on lightness in a boat[4].

There are several notable racing yachts that were designed to the Universal Rule or the International Rule. One of the most famous examples is the J-Class yachts, which were built to the specifications of the Universal Rule.

The J-Class represents the golden age of racing for the America’s Cup in the 1930s. Designers had to produce a J-Class yacht which had a rating of between 65 and 76 feet. This was not the length of the boats but a product of the limiting factors of the rule’s equation. Any of the determining factors such as length, displacement, or sail area could be changed, but such changes required proportionate change in other factors to compensate. This allowed them to be raced on a level basis37.

The J-Class yachts were the largest constructed under the Universal Rule and were the first yachts in an America’s Cup match to be governed by a formal design rule. The most famous J-Class yachts include the three original surviving Js – Velsheda, Shamrock, and Endeavour – which have been refitted for worldwide cruising and racing.

Yacht club

Royal Ulster Yacht Club

In total, nine J-Class yachts are active now with six replicas having been built since 2003; Ranger, Rainbow, Hanuman, Lionheart, Topaz, and Svea9.

The Universal Rule also produced other famous classes, especially Class M and Class R, which were very popular on the West coast4.

On the other hand, the International Rule, also known as the Metre Rule, has produced some of the world’s technically most refined yachts for over a century. As naval architects learned more about the variables that make yachts go fast, the International Rule yachts remained at the forefront of development8.

One of the most famous classes of yachts designed to the International Rule is the 12 Metre class. These racing sailboats were designed to the International Rule and were used in the America’s Cup racing from 1958 until 19874. The 12 Metre class yachts are considered some of the most fascinating racing yachts ever built, with their beauty, size, and association with the America’s Cup6.

Another notable class is the 8 Metre class. These yachts have remained at the forefront of development, presenting an intellectual challenge that only the very best naval architects were able to master. The complexity of the rule has led to the creation of yachts that are not only fast but also aesthetically pleasing, ensuring a new lease on life as a pretty and fast cruising yacht when their racing edge is lost5.

Sailing St. Francis 9, a 6 Metre class boat, skipper Ben Mumford and his crew defended the historic Alexandra Cup in a match race held on English Bay Sept. 13 and 14, 2008.

As mentioned, the International Rule does not restrict size, and many individual classes were created under it. This allowed designers a degree of latitude, yet controlled unsafe extremes. It laid down construction rules and governed the use of materials, yet understood that the Rule must develop1.

As mentioned, the International Rule has produced a variety of notable racing yachts, with the 12 Metre and 8 Metre classes being among the most famous. The 6 Metre was used in the resurrection of the Alexandria Cup after 99 years. These yachts are celebrated for their technical refinement, aesthetic appeal, and the competitive racing they have facilitated.

The Universal Rule and the International Rule do not overlap. The USA did not initially adopt the first International Rule and continued with the Universal Rule based on the formula developed by Nathanael Herreshoff[3]. After 1937, smaller boats were desirable, and so the International Rule gained popularity in the 12 Metre Class and smaller, to the detriment of the J Class, M Class and Q Class yachts[10].

In summary, both the Universal Rule and the International Rule were developed to allow yachts of different designs to compete fairly in races. However, they differ in their approach to yacht design and the factors they consider in their rating formulas.

In April 1914, the newspapers touted the first Lipton Challenge Cup Race, scheduled as part of Seattle’s Potlatch celebration. This regatta used the new R Boat, devised according to the Universal Rule, rather than 29 raters under the International Rule.

Several clubs had promised to send competitors, but most dropped out prior to July. Just four months before his death in 1960, Ted Geary commented on this situation:

“The Canadians in Vancouver quickly challenged and named their R Boat the Turenga, designed by E. B. Schock. The Seattle group was quick to provide defenders: Spray, designed, built and financed by Quent Williams, a prominent member of the Seattle Yacht Club; a second boat named Defender was financed by Joseph T. Parker from designs by L. H. Coolidge; a third one by a Seattle Yacht Club syndicate consisting of 0. O. Denny, P. J. Bernstein, F. T. Fischer, L. E. ‘Ted’ Geary, John Graham, Sr., W. G. Norris, and Edgar Webster. The syndicate quickly named her Sir Tom after the donor of the cup.”

By a margin of slightly less than two minutes, the Seattle sloop Sir Tom, skipper Ted Geary, won over the Vancouver challenger for the Sir Thomas Lipton Cup, the Turenga, Skipper Ronald Maitland, in a twelve-mile windward-leeward race in Seattle Harbor yesterday afternoon. The successful defense of the Lipton Trophy by the Sir Tom means that the Seattle Yacht Club, under whose pennant the Geary boat sailed, will have the honor of placing the first plate on the great wooden base of the magnificent trophy.” The Seattle Times,

The Seattle Times, July 18, 1914

Lipton was a Freemason (Scotia lodge no. 178). He was elected a member of the Royal Cork Yacht Club (1900) and of the Royal Irish Yacht Club (1906), and was an honorary member of the New York Yacht Club. He was honorary colonel of the 6th Bn Highland Light Infantry, and a freeman of Chicago and the city of Glasgow (1923). Knighted (1898), appointed KCVO (1901), and created a baronet (1902), Lipton died on 2 October 1931 and is buried, with his parents and siblings, in the Southern Necropolis, Glasgow. A rose (R. rugosa alba) was named after him by a US breeder in 1900. There are many photographs and a cartoon in Vanity Fair (19 September 1901). He never married, and left much of his fortune (nearly £1 million), papers, and artefacts to the city of Glasgow for charitable uses.

Sir Thomas Lipton, a knight so grand, in the tea trade made his name, His legacy in the Lipton Cup, added to his fame. From the Royal Victoria Yacht Club, to Seattle’s bustling bay, His influence on the sailing world, is still felt to this day.

So here’s to Lipton, Geary, Monk, and the clubs that bear their mark, To the Spirit of Seattle, and the yachts that sparked a spark. In the annals of the sailing world, their stories brightly glow, A testament to the passion, and controversy that racing sailors know.

In the heart of the Emerald City, where the waters meet the land,

Lived a man named Ted Geary, with a draftsman’s skilled hand.

He crafted vessels swift and sleek, like the Sir Tom in its prime, And raced them ’round the Puget Sound, beating the clock’s chime.

In the year of 1909, the city’s spirit soared, With the Alaska Yukon Pacific Exposition, Seattle was adored. “Spirit of Seattle,” the slogan of the day, Echoed in the waterways, where the racing yachts did play. The Spirit 2 and Alexandria, they danced upon the waves, Competing for the glory, and the applause of the brave. From the Seattle Yacht Club, to Victoria’s royal shore, There names are etched in history, their legends we adore.