Boats can be split into two categories: the ones that dig holes in the water and the ones that travel on top. Race boats, runabouts, fast cruisers, sport fisherman and military patrol craft are part of the planing fraternaty. A few racing sailboats and wind surfers fall into the same cult…

Ralph Naranjo Ocean Navigator pg 22 November/December 2006

To understand how a fast sailboat can also safely motor fast it is useful to consider the CLAMS (Classic Ancient Mariners). These men and women row on Green Lake, which I can see from my Seattle home and on the Montlake cut as far as the Ballard Locks from Lake Washington. Carbon-fiber shells are used these days.

Ballance

Rowing looks gentle, like sailing, but there is a certain violence and a definite acceleration involved at the start of a race. The shells are tippy vessels with the lowest of freeboard and yet on any morning that a pleasure boat might make way through the cut, they will. Stability is gained by balance. The balance of the extended oars and attention to the details of catching, driving, feathering and recovery. These vessels rocket. A sailboat built for high performance sailing is similar. The form presented to the water when under sail will be thin and shell-like or as is sometimes stated racing-canoe like. That is a simlar shape presented by the Murrelet when heeled at ~17 degrees.

Murrelet doesn’t have oars for balance, instead she has water ballast tanks as far from the centerline as possible, which provides stability like extended oars would and maximum hull speed is reached with wind that is normal when heeled between 15 and 20 degrees. A sailboat that is sailed at an angle of heel greater than 25 degrees has to much sail up or needs more ballast. There is a physical law that limits maximum speed in displacement hull vessels. The law dictates that the smaller the length of the vessel at the water line, the slower the maximum possible speed. It has to do with the inability of a displacement hull vessel to climb its own bow wake. The Mac26x hull design is displacement like in the bow but is a planing hull further aft. Hence by moving crew aft and reducing heel to 10 to 15 degrees it is possible to break out of displacement mode and reach planing speeds.

This allows Murrelet to power or sail over her own bow wake thereby both motoring and sailing at fast speeds. To reach planing speeds under sail live ballast (passengers) are moved aft so that the planing part of the hull can do its work in climbing the bow wave and then forward to pop the boat over the top. Mac26x cruisers plane when they have exceeded their displacement hull speed, which is calculated at 6.3 knots (7.2 MPH)

The Murrelet also has a “powerboat underbelly” which comes into play while turning at Wide Open Throttle (WOT). As the cruiser turns, to retrieve a water skier for example, the belly provides bouyancy preventing the boat from flipping. Most Mac26x captains, especially those who have mounted 70 hp motors, will reduce speed before turning just as the CLAMS and smart ski boat operators will. Editors of the February 15 through March 15 2006 Nor’westing conclude “The MacGregor 26 remains a popular and appropriate choice for boaters anxious to enjoy a single vessel that can be a very good sailboat as well as a very good powerboat. Enthusiastic MacGregor owners probably wonder why other boaters would ever settle for a boat that is only a powerboat or only a sailboat.

BAY AND DELTA MAGAZINE EVALUATION OF THE MACGREGOR 26

Note: The following article applies to the 26X, recently replaced by the 26M. However, the boats are very similar, and many of the comments relating to the X will be applicable to the M. We will post new reviews and comments on the boat as they are received.

(PHOTOS ARE NOT INCLUDED TO SAVE DOWNLOADING TIME)

The following article appeared San Francisco based Bay and Delta Yachtsman, in the December, 1997 issue. It was written by Ron Menet,

MACGREGOR 26X- FAST UNDER POWER OR SAIL

It had been a terrific day of sailing on San Francisco Bay. A wonderful westerly breeze had allowed us to sail all the way to the Carquinez Bridge, making an average of about ten knots. We came about ready for a pleasant run back to our Alameda marina. Everything was perfect-a nice breeze, good company, a nice boat-when suddenly, and without warning, the wind simply died. Not a breath was stirring and San Pablo Bay was like a mirror.

We drifted along for a while, hoping for a return of the wind, but eventually we fired up the auxiliary engine and headed for home. Our speed for this trip would never exceed six knots. The sun set hours before we reached our marina and an idyllic day had deteriorated into a long and painfully slow trip home. My guest – no sailor – asked, “Why can’t they put a big enough engine in a sailboat to make it go faster?”

“Because it’s a sailboat,” I answered. “Sailboats don’t go exceptionally fast under sail or power.”

The above is a fictitious tale. It never happened to me. I’m a powerboater, not a sailor- although I was a sailor a long time ago. But, over my years on the water, variations on the story have been told to me at various times and locations. I recall one sailor in particular, sailing the San Juan Islands, who actually found himself going backwards under power due to the force of the tidal current. In another more recent example, I voyaged 450 miles in the company of a 42-ft. sailboat that plodded along at a scant 6 – 7 mph all day, under power.

There are a few exceptions to that slow boat statement but, overall, it holds water. The hull of most sailboats is a displacement design; meaning the hull pushes through the water rather than lifting and planing across the water’s surface. Sailboats are also heavy boats with cast iron or lead in their keels to provide stability under sail. Pushing all of this through the water takes a lot of energy. But, within reason, placing a larger more powerful engine in such a hull produces only small increases in speed, while dramatically increasing fuel consumption. The slant term for a sailboat auxiliary engine is “kicker”; an engine designed for occasional use only, usually for docking maneuvers or for transiting narrow twisty channels.

Many sailors have longed for a boat combining all of the features of a cruising sailboat but capable, under power, of getting them to the breeze, the next port, or back home when the wind dies, in a reasonable period of time.

YOU CAN HAVE YOUR CAKE TOO

Just such a boat exists in the form of the MacGregor 26X. Capable of 24 mph with a mere 50 hp outboard motor, as well as having a good turn of speed under sail, she seems like a perfect combination. I originally saw the 26X at the recent NCMA boat show at Jack London Square, where she sat on her trailer in one of the tents nestled amongst the water ski, fishing, and runabout boats. I spoke with Arena Yachts representative Eric Lowe who waxed glowingly of the boat. After a quick tour I knew this was a boat I had to test for myself. Gene Arena, owner of Arena Yachts of Alameda, Ca, was most gracious and accommodating in arranging for our on-the-water session in the 26X.

When I arrived at his office, Gene explained all of the philosophy behind the building of the boat and the means used by MacGregor in bringing those concepts to reality.

First was weight. Weight is important for a number of reasons:1) they wanted a boat that could be easily towed by the average family sedan;2) a lighter boat is easier to launch and retrieve on the trailer;3) every pound removed during production is one less pound to move on the road or water.

The finished boat weight a mere 2,250 lbs., empty. The trailer, and empty boat combined weigh in at about 3,000 lbs; well within the towability range of many family sedans.

To achieve this bantam weight was no easy task. Every item on the prototype was tested for strength and weight. In every instance lighter weight, but equally strong, alternatives were considered. The result is a boat totally without frills, You’ll find no fine joinery in the cabinets or brightwork topsides. Other than for the covers on a few storage hatches in the cabin, you’ll find no wood on the boat at all. In fact, the boat is built from three main components – a hull, a hull liner, and a deck. No chopper guns are utilized, as the layers of lamination are all hand laid using cloth, mat and roving.

More weight savings can be found in the rigging which, but most sailboat standards, is quite light. You probably wouldn’t want to venture into the Roaring 40s with this boat but, for Bay-Delta, or lake sailing, and coastal cruising in the right weather, she’d perform just fine.

After weight came the underwater hull shape, in this case a rounded forward section gives way to a nearly flat planing section aft with almost no deadrise at the transom. This allows the boat to operate in a displacement or semi-displacement mode while under sail but still rise up on the planing sections when under power.

The boat incorporates a fully-retractable centerboard and a pair of transom-mounted rudders, for use when sailing. When under power, these are unnecessary, as the outboard motor is used to steer the boat.

THE BALLAST IS FREE

As mentioned, there is no lead or cast iron ballast. Ballast for sailing is provided by water stored in two reservoirs beneath the cockpit deck and the forward part of the cabin. Converting the boat from a power cruiser to a sailor is quite simple. A tank sealer (similar to the plug used in transom drains) is removed from the stepdown into the cabin and a waste gate (identical to those used in RVs at the outlet of their holding tanks) located on the transom is pulled open. Water begins to flow into the hull through the waste gate and flows forward through hollow stringers.

In a short 6 to 8 minutes, the tanks are full and the boat has taken on 1,500 lbs. Of free water ballast – ballast you don’t have to haul as you power or tow the boat. After sailing, fire up the engine, open the plug and waste gate and, because of the boat’s slightly bow-up attitude, the water flows back out the transom. It’s an ingenious system that has been adopted by other trailerboat builders.

Ballasted, the boat is remarkably stable. In fact, she is self righting. With the positive flotation built into the hull she’s also unsinkable. With me standing on a cockpit gunwale, she leaned every so slightly, and I’m a big guy.

Below deck the boat is remarkably roomy for a 26-footer. You could even sleep six folks down there in beds, but I wouldn’t. Six adults on a 26-ft. boat is at least two adults too many. Under the cockpit is an enormous sleeping area. It’s actually larger than a standard king-sized bed. Sitting headroom is provided at it’s forward end on both sides. Just inside the cabin access hatch on the starboard side is the private head compartment with solid door. This tiny room contains a built-in sink with water pump and a Porta-Potti. Forward of the head, but still on the starboard side of the cabin, is the dinette, also convertible to sleeping for two or sitting for up to five. The dinette seating is raised enough to allow an outside view through the side windows or the two located at the forward end of the cabin. You can place flat charts or family photos under a clear plexiglass panel in the table. Forward is a full double berth in the V.

The starboard side of the cabin, between the V and the large bunk aft, is the galley console. It contains a one-burner alcohol stove, a sink with water pump, a storage or pantry locker, and several shelves and bins on its front for other gear.

It’s all very neat and compact. Pleasant woven fabrics cover all of the cushions which, should the need ever arise, can all be removed and the interior of the boat washed out with a hose. There’s absolutely nothing down here other than the cushions which could be harmed by water.

The overall effect, however, is very plastic. The hull liner has a white gelcoat finish which is not the prettiest below-deck material to look at. The sole is also white gelcoat covered in a removable carpeting. One could, I suppose, begin to cover some of this plastic with wall coverings or carpeting, but you’d only be adding to the weight of the boat – a big no, no – and the chances of mildew and other nasty stuff. Basically, if you like the boat, you probably won’t be much bothered by the gelcoat interior.

DOES IT WORK?

So how does it sail? We powered out of the Oakland Estuary at between 15 and 19 mph onto San Francisco Bay looking for some wind. The 40 hp Honda four-stroke outboard seemed completely up to the task. With 50 horses, I’ve seen video of a sistership pulling a water skier. In every way she felt and acted like most powerboats of this size I’ve handled previously. I took her through several tight 360-degree turns, several figure eights, and crossed the wakes of several large boats finding nothing out of the ordinary.

The Bay, between the Estuary and the Bay Bridge was glassy calm. Continuing under the bridge towards Alcatraz Island we begin to find a little breeze and, somewhere between Alcatraz and Pier 39, we picked up enough that Eric suggested we kill the engine and try sailing. We flooded the ballast tanks, dropped the centerboard and rudders and hoisted the sails. The sail hoist was made especially easy by the roller-reefing of the 150 percent genoa (optional). With the roller equipment, the jib or genoa simply roll themselves up like a window shade, unwinding just as easily. With this setup, trips to the foredeck are minimized or eliminated. Mainsail hoisting is done from the side deck or cabin top.

We mutually agreed the wind was blowing at only 6 to 8 mph, but I soon had the 26X moving at better than 5mph toward Alcatraz (I’ve seen video of this same model boat in 25 mph winds and handling them nicely under reefed sails). Heading into the breeze she seemed to point quite normally and, off the wind, picked up a little speed. I would have liked more wind in order to better evaluate her sailing performance, but the zephyrs of the day were all that were available. Blame it on El Nino; it’s been blamed for everything else.

RACE, ANYONE?

It’s said that whenever two sailboats come together a race ensues, and I proved the saying. A 33-footer sailed by on the opposite tack and we came about to give chase. She pulled away (more sail and a longer waterline) but not rapidly. The manufacturer claims speeds of up to 18 mph under sail and spinnaker in heavy breezes.

Operating the boat is very comfortable. The optional suntop or bimini can be put in place quickly while operating the boat under power or sail. All of the sheets and halyards are in the cockpit, making single-handing her a breeze. The two small Lewmar sail winches are located on either side of the cabin top. The standard wheel steering and helmsman seat are comfortable and natural feeling and the small binnacle is large enough to accommodate some instrumentation. The after bulkhead of the cabin structure could hold even more and still be close enough to be readable by the helmsman.

So, overall, impression was very positive. Consider for a moment the whole package: 26-ft boat, sails, motor, and trailer , at a list price of less than $23,000. That’s an attractive package. Combine that price with a nice cruising sailboat that can be quickly and easily converted into an eager powerboat and you see why more than 36, 000 boats have been sold by MacGregor. You could buy a more expensive boat, a fancier boat, but if you consider bang for the buck, you may not find a better boat for the average Bay or Delta, or lake cruiser. You’ll also probably go a lot slower under power than you would in the MacGregor.

Speaking of the trailer, it is built by MacGregor specifically for this boat. It looks a bit light, but years of use and experience by thousands of owners have shown it to be up to the task. It is a one-axle trailer with guide posts at its stern and have a large V-shaped fitting for the bow making loading a simple drive-on operation. At the winch end of the trailer there is even a ladder to make boarding the boat from the trailer an easy task. Neither you nor your tow vehicle need to get wet in launching or retrieving this boat.

THE BIG CHOICE

Your choice of motor and propeller will impact the cost of the boat, obviously. You’ll have to face the two-versus four-stroke controversy, though most engine manufacturers are coming out with clean running, fuel-injected, two-strokers now. If you opt for a little kicker of ten horses or so, the price would come down. If, on the other hand, you choose an outboard in the range recommended by the builder – 40 to 50 hp – you’ll spend a little more but get the satisfaction of using all of the capabilities built into this interesting boat.

The boat comes equipped with a full set of working sails – main and jib. Optional sails from the factory include the 150-percent genoa and a spinnaker that requires no spinnaker pole. This latter means no one has to be on the foredeck during jibing maneuvers.

The rigging, as I mentioned earlier, looks a little light, but that could be modified by an owner so inclined, with a mind to keeping the weight in check. The mast can be raised and lowered by one person, either directly or through the use of the optional pulley system and sail winches. Once up and in place, only the forestay needs to be fastened at the bow, since all of the other shrouds and stays remain attached at all times. It’s so easy, that out on the water you might do it just to get under a bridge to see what’s on the other side.

Heading back under power to the Arena Yacht Sales dock in Alameda, I reverted to a typical powerboat form, chuckling as I passed the numerous sailboats slogging their way home on their kickers. You may not always want to steam along at 19 to 25 mph but it’s sure nice to know you can if you want to, and it’s fun to wave at all of the sailboats you leave in your wake.

The MacGregor 26X deserved a close look if you’re in the market and you can get one at Arena Yacht Sales in Alameda. Call Gene or Eric for an appointment at 510/523-9292.

In 1979 all boat racing was done under IOR, but it was already in decline, mainly because designers had found their weaselly way into the rule,’ says the former Royal Ocean Racing Club (RORC) technical director Mike Urwin, ‘which meant that unless you had the latest and greatest you didn’t stand a chance. The IOR produced boats which wholly optimised the rule but which were opposed to the rules of nature, such as hydrodynamics.’

One of the main complaints about the IOR was that it produced boats which were ‘short on stability’, as Urwin puts

Post by Nick Moloney.

What are the active rowing clubs in the Pacific Northwest? Where there any Sailing, Athletic or Yacht clubs in the Pacific Northwest that started out as rowing clubs?

The Pacific Northwest is home to a variety of active rowing clubs. Some of the notable ones include the Lake Washington Rowing Club, Oregon Rowing Unlimited-PDX, Pacific Rowing Club, Green Lake Crew, Station L Rowing Club, and Lake Oswego Community Rowing1356713.

The Lake Washington Rowing Club, based in Seattle, offers a variety of programs for adults, from Learn to Row through Competitive Rowing1.Oregon Rowing Unlimited-PDX is a non-profit rowing club for youth and adults in Portland, Oregon3. The Pacific Rowing Club, established in 1980, caters to the youth of San Francisco5. Green Lake Crew, based in Seattle, has a rich history dating back to the 1950s6. Station L Rowing Club is a prominent club in Portland, offering learn-to-row classes and participating in regional regattas7. Lake Oswego Community Rowing operates from the Charlie S. Brown Water Sports Center on the Willamette River and offers programs for everyone aged 12 and up13.

As for clubs that started as rowing clubs, the Olympia Yacht Club is a notable example. From 1904 to 1915, it was known as the Boat and Rowing Club of Olympia8. The Seattle Yacht Club also has a history of supporting rowing. The club has been involved in promoting the University of Washington’s rowing program and the Montlake Cut as a premier rowing venue4. However, it’s important to note that these clubs have evolved over time and now encompass a broader range of maritime activities.

Is there rowing club in Olympia that operates out of the Swantown Marina? What is the history of the rowing club in Olympia?

Yes, there is a rowing club in Olympia that operates out of the Swantown Marina. The Olympia Area Rowing (OAR) is a non-profit rowing club that serves youth and adult athletes from the communities of Olympia, Lacey, and Tumwater in Washington state. OAR operates its own boathouse at Swantown Marina, located at the base of Budd Inlet on Puget Sound13.

The Olympia Area Rowing Association was originally organized in the 1980s and re-founded in 1998 by five local rowers. The club has grown to over 80 adult members, more than 40 high school students, and around a dozen middle school students. In the early days, OAR members kept their boats outside in what was called “The Compound” – an adjacent parking lot. The OAR boathouse, designed by club member Gretchen Van Dusen, was completed in 2005, and is located on property owned by the Port of Olympia. The 5,300-square-foot building is currently home to both OAR and the Olympia Parks, Arts, and Recreation Department water recreation programs4.

The club promotes competitive and recreational scull and sweep rowing for adults and youth, fostering sportsmanship, teamwork, athleticism, and camaraderie. It offers organized adult rowing programs with scheduled practice times, an active group of adult recreational rowers, and a robust youth rowing program. Youth between 9th and 12th grade can participate in the high school program, and youth in 7th and 8th grades can participate in the middle school program16.

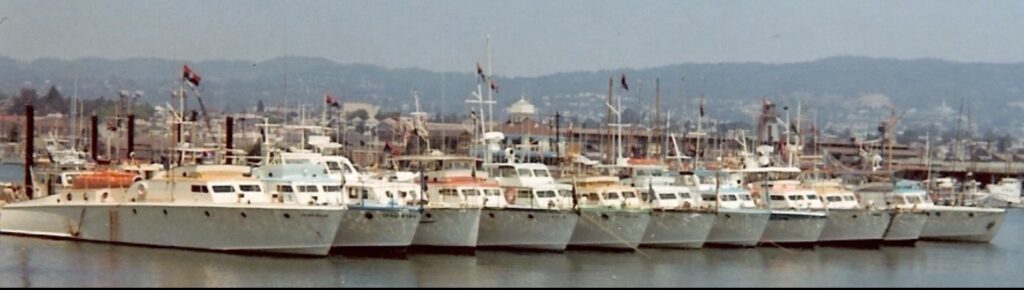

Swantown Marina, where OAR is based, is the seventh largest marina in Washington State and is the center of recreational boating activities in the South Sound. With over 650 permanent slips, as well as 70 guest slips, Swantown is home to a diverse boating community313.

In the Pacific Northwest, Do the sea scouts have rowing races and rowing performances? What boats do they use? What events have the competitions? Are the boats used for sea scout competitions better suited for salt water and why?

Sea Scouts in the Pacific Northwest, as part of their activities, do participate in rowing races and performances. The types of boats used by Sea Scouts can vary greatly, ranging from paddlecraft like kayaks, canoes, and stand-up paddleboards, to larger sailboats and powerboats810. The Lelievlet, a steel sailing and rowing boat, is commonly used by Sea Scouts in some regions2. However, not every ship needs to own a boat; some councils and other community organizations have paddlecraft and small boats that Sea Scouts can use6. Whaleboats are one example.

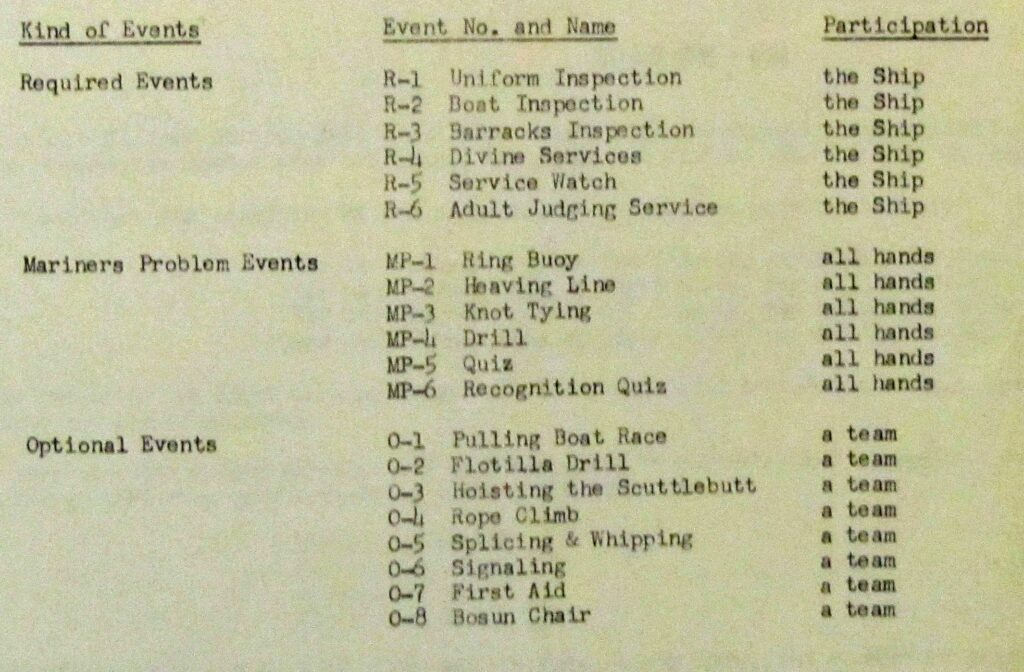

Sea Scout competitions, known as regattas, are held regularly. For example, the Old Salts’ Regatta is an annual event where Sea Scout Ships compete in various events including knots, rope climb, scuttlebutt, flotilla drill, pulling, and piloting7. In Ireland, Sea Scouts host a Rowing Regatta as part of their annual events11.

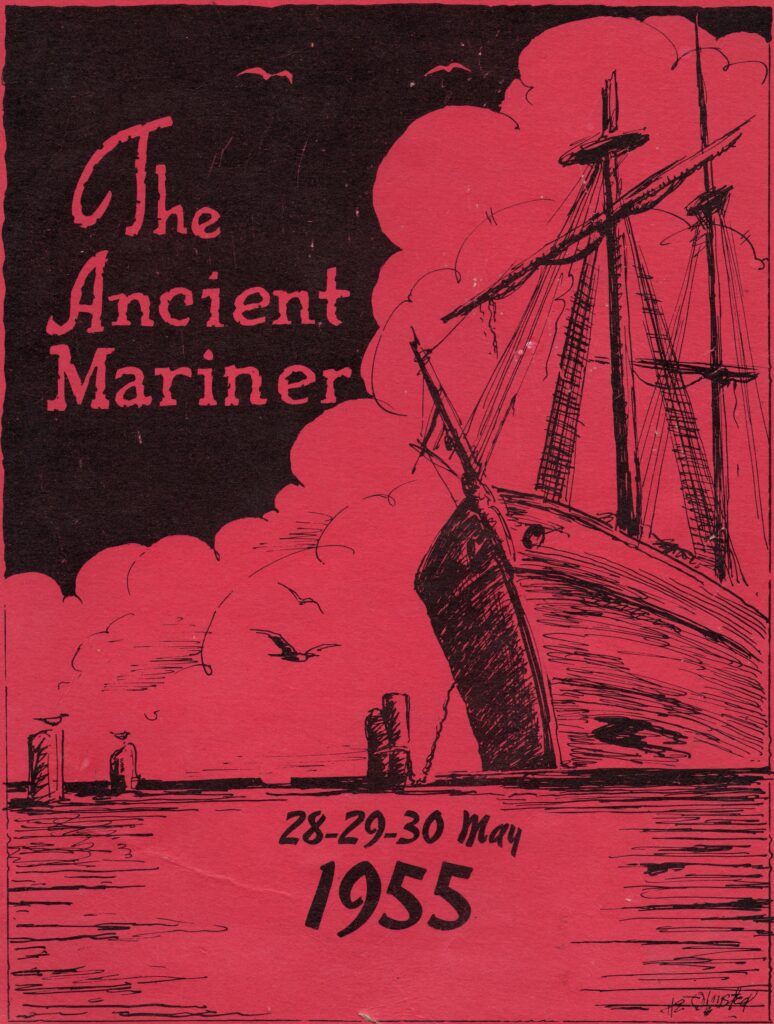

The Ancient Mariner Regatta (AMR) is one of the largest Sea Scout Regattas in the United States, with a history dating back to 1952. The inaugural event was held at Coast Guard Island and drew a large attendance, with an estimated 750 Sea Scouts participating. Over the years, the event has seen many changes, including the introduction of class awards and the evolution of the Regatta bulletin and events1.

The AMR was initially instituted as a Regional Regatta, Region 12. In the 1960s, the Regatta regularly had 2000 Sea Scouts. The first nine AMR boarding guides and “sea letters” artwork included a moored clipper and a sailing ship underway. The “Ancient Mariner” pictured on today’s boarding guide first appeared in 1962 for the tenth AMR, created by the late Lyle Galloway of the Navigator1.

At the Ancient Mariner Regatta, Sea Scouts use a variety of boats for competitions, including the 26-foot whaleboat 7. This boat is designed with eight gunnel mounted oars and is built to US Navy specifications. The rated capacity of this boat is 22 men, or the equivalent in terms of pounds of stores, 227.

Before being used for competition, these boats had different uses. The 26-foot motor whaleboat, for instance, was used by the US Navy for various purposes. Whaleboats have a long history of use for hunting whales, hence the name. They were designed to be sturdy and stable in rough seas, and their long, narrow shape made them fast and maneuverable, which was crucial for chasing and harpooning whales.

whaleboats are used in a precision rowing event flotilla at the Ancient Mariner Regatta. The precision event is called the “Whaleboat Flotilla” and involves a team of eight rowers in a 26-foot motor whaleboat rowing in unison to perform a series of maneuvers with precision and accuracy14. The components of the precision event include:

- A team of eight rowers in a 26-foot whaleboat

- The rowers must row in unison to perform a series of maneuvers with precision and accuracy

- The maneuvers include rowing forward, backing, turning, and stopping the boat

- The team must also demonstrate their ability to safely handle the boat in a variety of conditions, including rough water and tight spaces

- The event is not timed, the team with the most precise execution of the maneuvers wins the competition.

The Whaleboat Flotilla is a challenging event that requires teamwork, communication, and skill. It is a testament to the historical uses of whaleboats, which were designed to be sturdy and stable in rough seas and maneuverable in tight spaces. The event is a highlight of the Ancient Mariner Regatta and showcases the talents of Sea Scouts from across the country14.

Knot tying event

It’s important to note that the specific rules and regulations for the Ancient Mariner Regatta and the Whaleboat Flotilla may vary from year to year, and may be subject to change based on the needs of the event and the Sea Scouts organization. For example:

The home of AMR was Coast Guard Island, Alameda, CA until the tragic events of 9/11/01. After 9/11, the heightened level of security at the Coast Guard base could potentially prohibit the regatta from happening; as a result, the regatta was temporarily rehomed to the Sea Scout Base in Stockton, and then found a home on the aircraft carrier USS Hornet for several years. Today, the regatta calls the California Maritime Academy (CMA) home2.

In the context of the Navy, the whale boats were used for ship-to-shore transportation, rescue missions, and other utility purposes. They were designed to be launched from larger vessels, providing a means of transport that could navigate in shallow waters where larger ships couldn’t go.

As for the connection to “Surf”, it’s important to note that these boats are designed to handle rough waters, which includes surf conditions. Their design allows them to cut through waves and maintain stability, making them suitable for surf and other challenging sea conditions.

In the Ancient Mariner Regatta, these boats are used in various events including seamanship, whaleboat races, sailing, piloting, and knot tying9.The skills required in these competitions reflect the historical uses of these boats, from navigating challenging waters to performing tasks essential to naval and whaling operations.

Rowing whaleboats in Sea Scout competitions presents several challenges, which can be categorized into physical, technical, and teamwork-related challenges.

Physical Challenges:

Rowing a whaleboat is physically demanding. It requires strength, endurance, and physical fitness. The rowers must be able to handle the weight of the oars, which can range from 11 to 15 lbs, and the physical strain of rowing for extended periods6.

Technical Challenges:

Rowing a whaleboat requires technical skill and knowledge. The coxswain is responsible for exercising smart seamanship in handling the boat and issuing commands to the crew. The crew must function together for the boat to properly handle. One Sea Scout popping an oar out of a rowlock can bring the boat to a stop; one side overpowering the other will cause the boat to turn. Learning to work together to steer a straight course is a fundamental step in learning to be a team2.

Teamwork Challenges:

Rowing a whaleboat is a team effort, and it requires excellent communication and coordination among the crew members. The crew must learn to work together, cooperate, and function as a unit. This is particularly important in a race, where the crew must row in unison to maintain speed and direction. If one member of the team is not in sync with the others, it can disrupt the rhythm of the rowing and affect the performance of the boat12.

Preparation Challenges:

Preparing for a competition like the Ancient Mariner Regatta (AMR) can be challenging. Scouts spend weekends upon weekends, often all three days, learning and reviewing information as well as teaching the new scouts all the tips and tricks to memorizing how to tie a bowline on a bight or the basics of operating a rowboat, and the proper form of sailing in a whaleboat4.

In conclusion, while rowing whaleboats in Sea Scout competitions can be challenging, it is also a rewarding experience that teaches valuable skills such as teamwork, communication, and leadership. It is a testament to the resilience and determination of the Sea Scouts, who have been rowing whaleboats for over 80 years1.

As for the suitability of boats for saltwater, it’s important to note that saltwater boats are designed to withstand the corrosive effects of saltwater and the damage that can be done by sea creatures. This means they must be coated on their bottoms with a paint that protects wood in salt water. But more to the point, they must have higher freeboard to withstand waves hitting them or swells capsizing them, than one finds on shells. However, the specific boats used by Sea Scouts can vary based on the activities they are engaged in and the resources available to them. Some Sea Scout groups may focus on one kind of boating, while others mix it up and try sailing, powerboats, and paddleboards8.

The AMR has a proud history of providing service to youth for over 60 years. Many Sea Scouts who competed in the Regatta as youth have gone on to continue their service in Sea Scouting and many have served in the military1. The regatta offers a unique method of scoring, where all ships have the opportunity to achieve Clipper Class (the highest award), as well as several individual awards such as the Great Republic2.

The Ancient Mariner Regatta includes a variety of events such as seamanship, whaleboat races, sailing, piloting, knot tying, and much more4. It represents a chance for Sea Scouts to showcase their skills, teamwork, and leadership within a friendly and competitive setting5. The event has been held annually, with a two-year hiatus due to the COVID-19 pandemic3.

In conclusion, Sea Scouts do participate in rowing races and performances using a variety of boats, and they take part in competitions like regattas. The suitability of their boats for saltwater depends on the capability of their crew as well as maintenance of the boat and its design features. These boats surf, which is a form of planing and can be towed by a larger vessel or a whale at speeds exceeding hull speed, without loss of hull integrity.

Sea Scouts have a formal partnership with the Coast Guard Auxiliary. In August 2018, an agreement was made between the United States Coast Guard Auxiliary and the Boy Scouts of America, making Sea Scouts the official youth program of the Coast Guard Auxiliary12. This partnership allows Sea Scouts to benefit from Coast Guard seamanship and vocational training, while also introducing them to the Coast Guard1. It also allows the Coast Guard Auxiliary to charter Sea Scout Whaleboats.

The partnership encourages Sea Scouts who are at least 14 years old to apply for Auxiliary membership. Local Auxiliary flotillas and divisions are encouraged to charter Sea Scout Ships1. All Sea Scouts and Sea Scout leaders automatically become Associate Members of the Coast Guard Auxiliary Association, and they can choose to become full members of the U.S. Coast Guard Auxiliary by following the normal application process35.

The affiliation of Sea Scouts with the Coast Guard Auxiliary offers several benefits to both parties.Benefits to Sea Scouts:

- Access to Training: The partnership gives Sea Scouts an opportunity to benefit from Coast Guard seamanship and vocational training, which can enhance their skills and knowledge in maritime activities17.

- Introduction to the Coast Guard: The affiliation introduces Sea Scouts to the Coast Guard, providing them with a unique insight into the operations and responsibilities of this maritime service17.

- Use of Facilities: Sea Scouts are authorized to use training and recreation facilities at Coast Guard facilities and to participate in Coast Guard cruises and air operations at the discretion of Commanding Officers or Officers-in-Charge, with approval of the District Commander, and in accordance with applicable Coast Guard policies5.

- Membership Opportunities: Sea Scouts who are at least 14 years old can apply for Auxiliary membership, and all Sea Scouts and Sea Scout leaders automatically become Associate Members of the Coast Guard Auxiliary Association. They can also choose to become full members of the U.S. Coast Guard Auxiliary by following the normal application process136.

Benefits to the Coast Guard Auxiliary:

- Youth Engagement: The partnership allows the Coast Guard Auxiliary to extend its message about safe boating and maritime careers to more young people7.

- Potential Candidates: The affiliation could potentially provide the Coast Guard Auxiliary with future candidates for the Coast Guard Academy7.

- Community Outreach: The partnership enhances the Coast Guard Auxiliary’s community outreach and engagement efforts, as Sea Scouts are a program for religious, fraternal, educational, and other community organizations to use for effective character, citizenship, and mental and personal fitness training for youth6.

In conclusion, the affiliation between Sea Scouts and the Coast Guard Auxiliary is mutually beneficial, providing Sea Scouts with valuable training and exposure to the Coast Guard, while also helping the Coast Guard Auxiliary extend its reach and influence among young people17.

This partnership began in Maryland, North Carolina, Virginia, and portions of New York, Ohio, and Pennsylvania before a nationwide rollout2. It is important to note that while Sea Scouts can become members of the Coast Guard Auxiliary, they must meet all Coast Guard Auxiliary membership eligibility criteria required by law and regulation, including background checks, payment of dues, and completion of any required training4.

Once upon a time, in the heart of the Pacific Northwest, a 14-year-old lad named Jack Tar embarked on a journey that would shape his life in ways he could never have imagined. Jack was a member of the Sea Scouts, a youth organization dedicated to maritime education and training. His vessel of choice was a 26-foot whaleboat, built to US Navy specifications, a sturdy and reliable craft that would become his second home.

Jack and his crew of fellow Sea Scouts spent countless hours on the water, learning the art of rowing Andy the science of seamanship. They learned how to keep the boat steady in rough waters, how to work together to maintain speed and direction, and how to use their collective strength and skill to win races and flotilla competitions.

One day, the crew decided to add a “ringer” to their team, a young man known for his strength but not his seamanship. The ringer’s raw power gave them an edge in the races, and they began to win more frequently. However, their success was short-lived. At the Ancient Mariner Regatta (AMR), a prestigious Sea Scout competition, their boat was disqualified when the ringer failed to show up for the mandatory knot-tying competition.

The disqualification was a blow to the team, but it also served as a wake-up call. Over the next year, the ringer worked hard to learn the knots and improve his seamanship. Jack and the rest of the crew supported him every step of the way, teaching him the skills he needed and helping him to become a valuable member of the team.

Their hard work paid off. For the next three years, Jack’s whaleboat won the racing competitions at the AMR. Their success was a testament to their teamwork, their dedication, and their resilience in the face of adversity.

After his time with the Sea Scouts, Jack married, had a son, and joined the Coast Guard Auxiliary, bringing with him the skills and experiences he had gained from his years of rowing and racing. He was by then called John because his son was named Jack and his son didn’t like being called Junior. He also bought a Macgregor 26x, a boat the same size as the whaleboat but designed with water ballast for stability instead of crew and extended oars. The Macgregor 26x was a reminder of his time with the Sea Scouts, a symbol of the journey he had taken and the lessons he had learned. He hoped young Jack would be so lucky.

In conclusion, Jack’s story is a testament to the power of teamwork, the value of perseverance, and the importance of learning and growing from our experiences. His journey from a young Sea Scout to a member of the Coast Guard Auxiliary is a reminder that every challenge we face is an opportunity to learn, to grow, and to become better versions of ourselves.