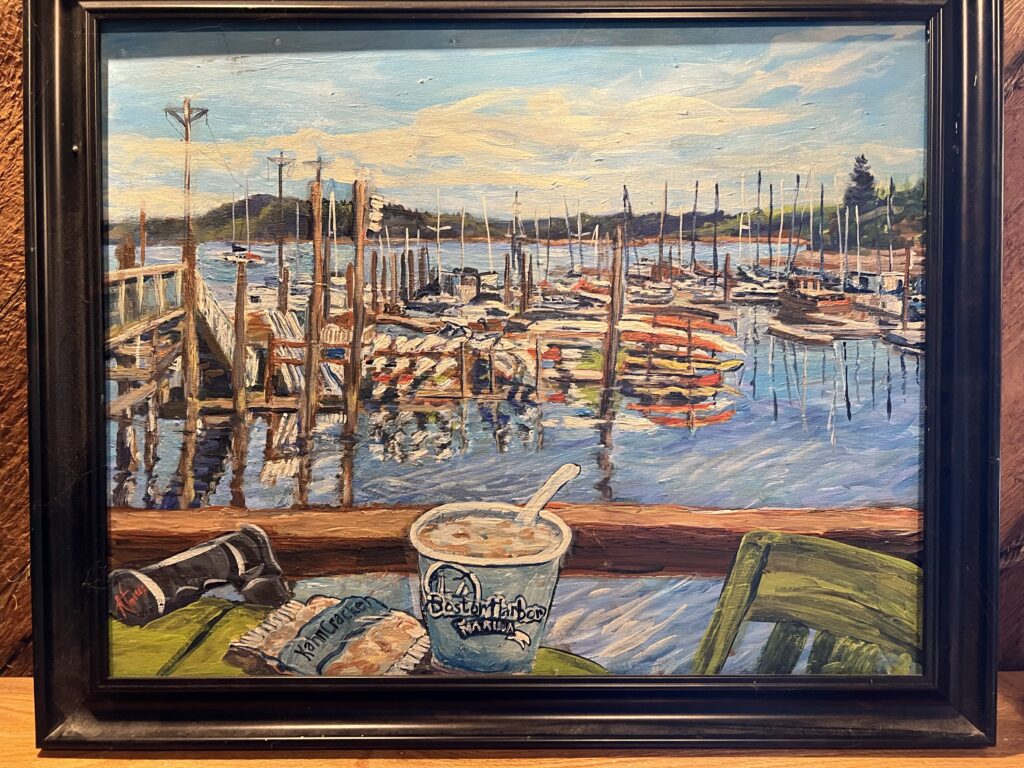

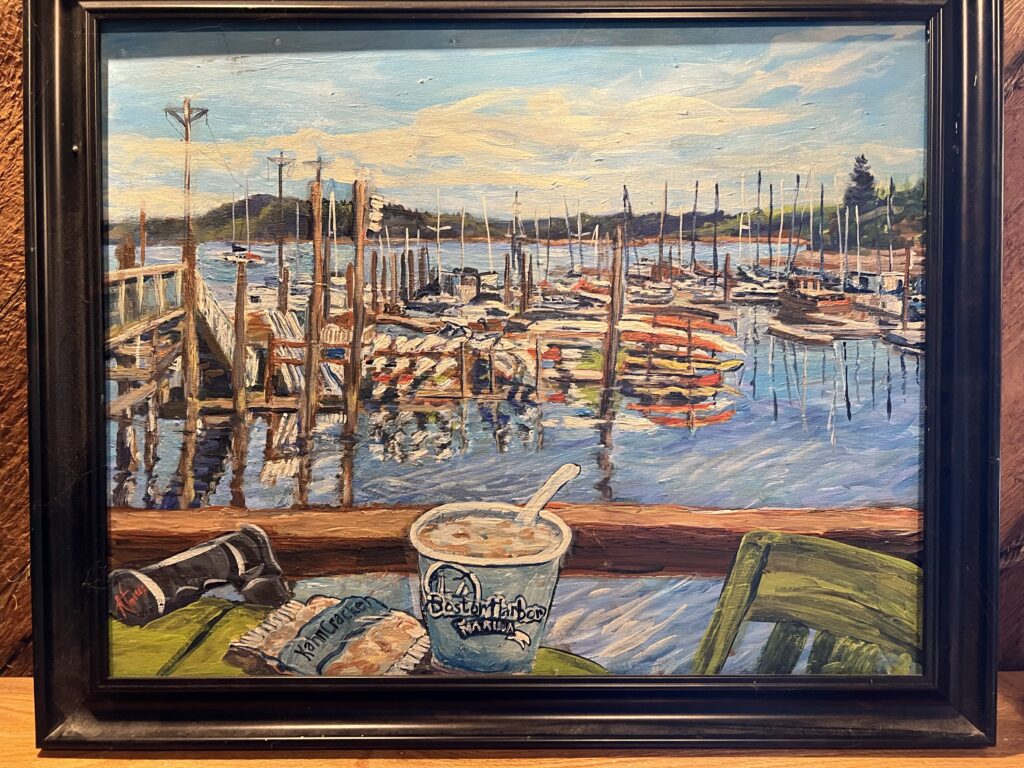

Boston Harbor, a small community just north of Olympia, manages to be a near-perfect overlap of South Sound boating, beer, and wildlife. The marina is the social and nautical center: classic wooden docks, a pocket beach, a county boat ramp, and a year‑round snack shack and tap counter looking out across Budd Inlet to the Olympics.

For a boater, a beer drinker, a wildlife enthusiast, and a birder, it is one of those rare spots where you can launch, moor, watch orcas and harbor seals, and drink a local IPA without ever moving your car.

For boaters, the practical access is excellent. Thurston County operates a 24‑hour public boat launch immediately adjacent to Boston Harbor Marina; the ramp is usable whenever the tide allows, and you can side‑tie at the marina’s guest dock to load or unload passengers or make last‑minute store runs.

The marina offers guest moorage by reservation, plus a handful of transient mooring balls mentioned in recent boater reports. A Puget Sound marina rate study lists Boston Harbor’s transient nightly fee at about 1 dollar per foot, summer and winter, but rates change and the marina does not publish a current sheet, so a quick phone call is essential for up‑to‑date pricing.

For launching human‑powered craft, you can either use the county ramp (typically Discover Pass/launch‑fee territory) or hand‑launch from the marina’s small beach.

For someone wondering about paddling out for a wine‑and‑cheese party, Hope Island Marine State Park is very much in reach from Boston Harbor, but it is a real sea‑kayak trip, not a casual putter.

A well‑regarded route description from Kayak NW gives a Boston Harbor–Hope Island paddle of roughly 7.3 nautical miles and about 3 hours in typical conditions, rating it SK II/III and warning that the Budd Inlet crossing and currents near the island require attention to tide and weather.

Club trips using Boston Harbor as the launch describe 12–13 nautical mile circuits that include Hope, Squaxin, and Harstine Islands, again stressing current timing and winter conditions. So yes, you can absolutely paddle over for a civilized picnic at the park’s tables and water‑trail campsites, but it is a trip for competent paddlers with proper gear and a tide plan, not an impromptu wine‑soaked drift.

Boston Harbor also works as a modest anchorage for cruisers willing to swing out rather than pay for a ball. Washington’s general rules for state‑owned aquatic lands allow vessels to moor or anchor for up to 30 consecutive days, and no more than 90 days in a year within a five‑mile radius, as long as you comply with any other local regulations.

The harbor itself is outside Olympia city limits and not within the stricter Percival Landing rules, though there is active local discussion about anchoring ordinances in Budd Bay generally. In practice, many visitors either pick up the marina’s transient mooring balls or anchor in deeper water clear of the dock approaches and traffic lanes, then dinghy in for ice, chowder, or a beer. Anchoring is, in that sense, “free,” but expect to be your own harbormaster and to stay well clear of the marina’s moorings and the small‑craft.

Creature comforts for transient boaters at Boston Harbor are fairly simple. Multiple paddling and trip reports emphasize that there are full, plumbed restrooms “just across the street from the Snack Shack at the top of the ramp,” which is one reason the spot is recommended as a launch for human‑powered craft.

However, neither the marina’s own materials nor regional boating guides list showers as an amenity, and reviews often refer only to public toilets rather than shower blocks. The safe working assumption is that you will have decent restrooms and plenty of food and drink, but not dedicated boater showers or laundry; if showers are mission‑critical, Swantown or one of the larger port marinas in downtown Olympia is a better base.

The food and drink side of the equation is where Boston Harbor really distinguishes itself for the casual visitor. The “Snack Shack” runs year‑round with breakfast sandwiches, chowder, fish and chips, burgers, and a kids’ menu, with an expanded kitchen added in the mid‑2010s specifically to support full breakfasts on weekends and regular lunch and dinner service. The covered deck is explicitly set up as a place to sit with a craft beer or glass of wine and watch the Sound; the marina showcases a long list of Northwest brews and wines and hosts local bands and brewery nights on summer Fridays.

This is not a white‑tablecloth Sunday champagne brunch, but in summer you can show up late morning, order eggs or a breakfast sandwich, and treat the deck as a very informal brunch spot with no extra charge beyond menu prices.

Wildlife‑wise, Boston Harbor is surprisingly rich for such a compact site. The marina promotes itself as one of the few public‑access docks in the area, explicitly inviting visitors to walk the classic wooden floats to look down at crabs, sea stars, anemones, sea slugs, and intertidal life, and to scan for otters, harbor seals, bald eagles, herons, and the occasional sea lion or orca. Local photographs and visitor accounts confirm resident harbor seals, particularly around haul‑outs toward Woodard Bay, and regular visits from river otters and great blue herons; Stock photography from the marina itself shows seals and herons using the dock and nearby pilings. The Estuarium and local educators run night‑time “Pier Peer” events off the docks, lowering lights and viewing plankton, shrimp, and juvenile fish, which is exactly the kind of thing that keeps a wildlife enthusiast or kid happy long after the beer drinker has settled in on the deck.

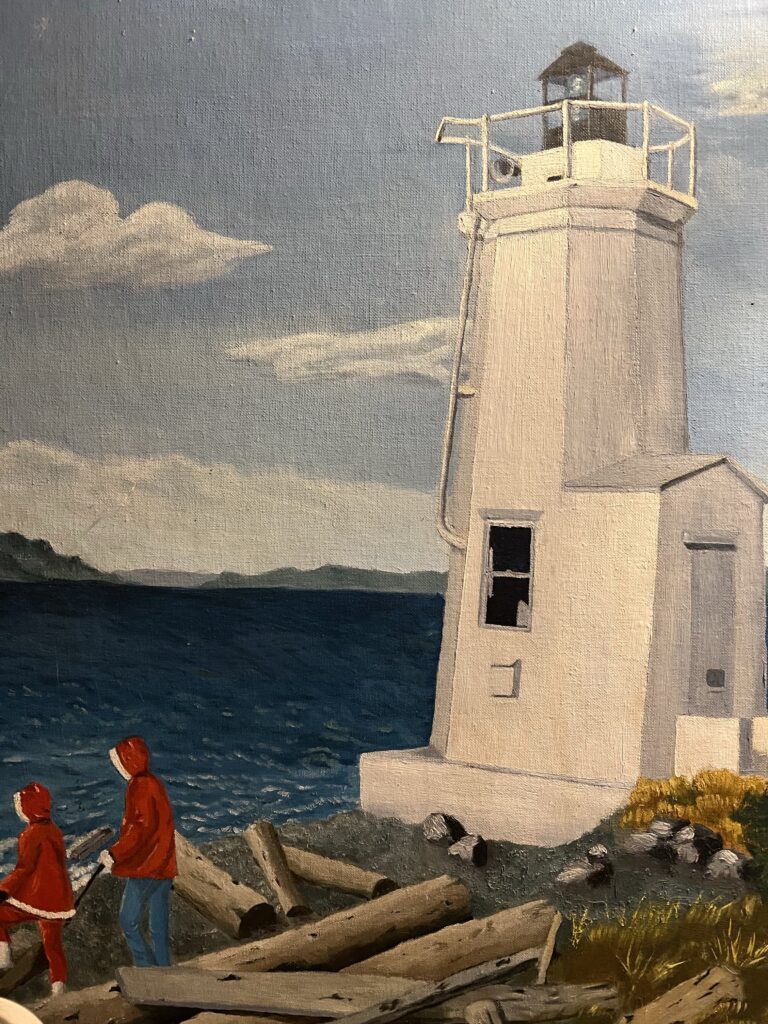

The tower sits on private land and is not open to on‑foot visitors, but you can get an excellent water‑level view of it from a kayak rented at the marina or simply by walking to the end of the public dock and looking northeast across the point.

For a birder, Boston Harbor is a convenient edge‑of‑town staging post. Right at the marina you can usually find gulls, pigeon guillemots, great blue herons, cormorants, and often bald eagles commuting along the forested shore or perched in the big firs behind the docks; in summer, people specifically go to Boston Harbor to watch the local purple martin colony swooping over the marina.

Gull Harbor lies just a short hop north of Boston Harbor up the east side of Budd Inlet. On the chart it is roughly 2 nautical miles from Boston Harbor to the entrance to Gull Harbor, depending on how directly you run, putting it well within an easy motor or sail and also a reasonable range for experienced paddlers in settled conditions. Historic planning and ecological reports identify Gull Harbor and its shoreline as a sensitive habitat area in Budd Inlet, noting both harbor seal use and great blue heron nesting; one such report references a great blue heron rookery and bald eagle nesting associated with a wildlife‑restricted area that includes Gull Harbor. Sailors’ notes on Budd Inlet also describe a heron rookery “through the middle of” the shoreline forest near the Gull Harbor entrance, reinforcing the idea that the trees in and around the harbor are active nesting habitat.

From an anchoring standpoint, Gull Harbor is used by small craft as a fair‑weather stop but must be treated with care. It is a shallow, narrow indentation on the east side of Budd Inlet, with obstructions charted near the eastern shore just south of the harbor entrance, and any anchoring must respect both state rules for aquatic lands (30‑day limits, no derelict moorage) and the ecological sensitivity of a seal haul‑out and heron rookery described in wildlife‑protection documents.

In practice, that means you can almost certainly drop the hook in a suitable patch of depth and bottom outside sensitive zones for a short, daylight visit in settled weather, but you should avoid crowding the head of the bay, stay clear of marked obstructions, and treat the area as wildlife habitat first and anchorage second.

A short drive or bike ride away, Woodard Bay Natural Resources Conservation Area is a major wildlife site, known for its harbor seal haul‑outs, large bat colony, and, critically for your question, a significant great blue heron rookery visible from the trails and viewing areas. Hikers, cyclists, and birders regularly describe Woodard Bay as a place to watch herons nesting in numbers and to see seals and birds in relative quiet, making it effectively “Boston Harbor’s rookery,” even if it is technically up the inlet.

By water, Woodard Bay is very close to Boston Harbor, but access is set up for hand‑carried boats rather than larger craft.

From Boston Harbor Marina to the mouth of Woodard Bay is roughly 3–4 nautical miles by the most direct shoreline route: down the east side of Budd Inlet and into Henderson Inlet, then into Woodard Bay itself. Trip‑planning pieces aimed at kayakers treat Woodard Bay as an easy half‑day outing from Boston Harbor Marina which is the closest rental and launch hub for paddling trips into Henderson Inlet and toward Woodard.[1][2]

Once you are at Woodard Bay, there is no developed deep‑water dock for visiting motorboats. The Woodard Bay Natural Resources Conservation Area is managed as a wildlife‑forward site, with access deliberately light. On the landward side, visitors park at the DNR parking lot, then walk a paved road roughly 0.7 miles to an overlook and shoreline; this trailhead also has a small seasonal hand‑launch area for kayaks and canoes, but not a marina‑style float.

For boaters approaching from the water in small craft (kayaks, canoes, or very small dinghies), the practical “landing” is to beach on the soft shoreline in suitable spots near the established access area or along the bay where it is permitted, taking care to avoid posted closures around seal haul‑outs and nesting areas. Larger powerboats and sailboats generally do not run into Woodard Bay itself; they either stay out in Henderson Inlet or treat the bay as off‑limits out of respect for the conservation focus and shallow, sensitive waters.[3][4][5]

The little beach immediately beside the Boston Harbor Marina is also good for the kind of “shelling” that means poking around at low tide. The marina invites visitors and their dogs onto its private beach, providing chairs and picnic tables, and the gravelly foreshore there and at the adjacent public launch turns up mussel and clam shells, barnacle‑encrusted rocks, and the occasional moon‑snail shell. For actual shellfish harvest, you would need to check Department of Health maps and seasons; for simply walking and beachcombing, the north‑South Sound beaches around Boston Harbor, Tolmie State Park, and Woodard Bay are all rewarding, especially on a big minus tide.

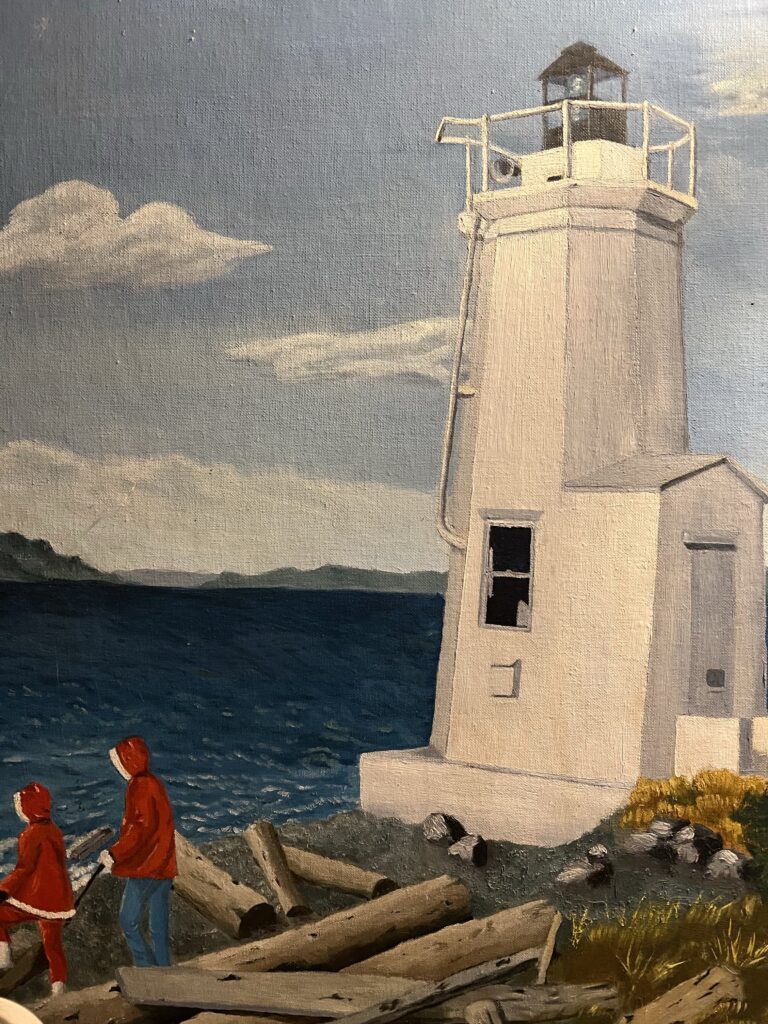

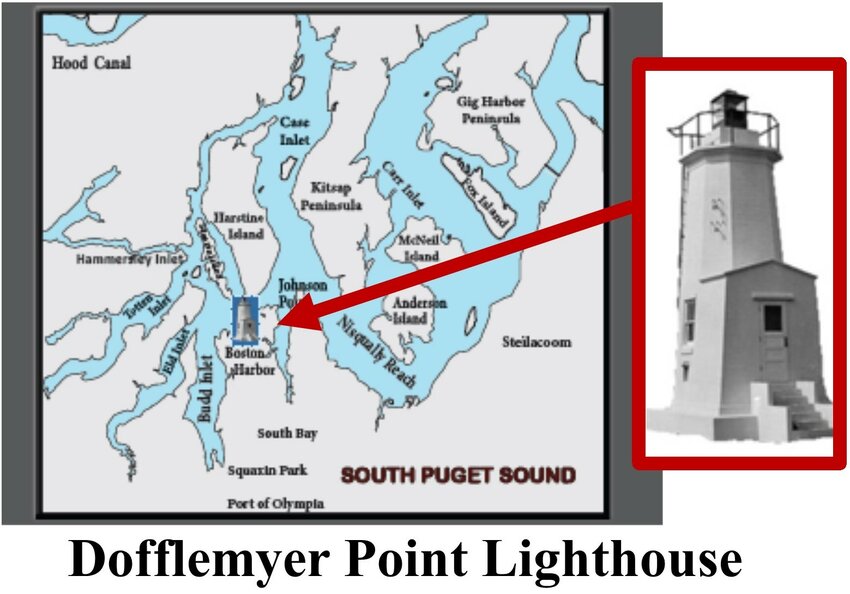

The lighthouse you see from the marina’s outer floats is Dofflemyer Point Light, and it is more than just a picturesque backdrop.

Dofflemyer Point Light marks the northeastern entrance to Budd Inlet and was one of the first lighthouses in Washington to be automated; it is the southernmost light in Puget Sound and still an active Coast Guard aid to navigation.

The first “light” there was nothing more than a lantern on a pole in 1887; the current 30‑foot concrete tower, designed by Rufus Kindle, dates from 1934 and was fully automated by the 1980s.

This style of lantern was used from 1837 to 1913 by the US Coast Guard. There were 33 lanterns on Puget Sound. Typically, fuel for a post lantern would last 8 days.

In terms of ownership and history, the marina itself is a genuine local institution. It dates to the late 1920s—1928 is the best local historian estimate—and has anchored the Boston Harbor neighborhood for nearly a century.

In 2014, when the previous owners put Boston Harbor Marina up for sale, longtime neighborhood residents Kate Gervais and her parents bought it, taking on a property that “needed a lot of love” in terms of docks, pilings, and infrastructure.

Since then, the family has systematically upgraded the facility: replacing creosote pilings with steel, installing new fuel dispensers, strengthening the main dock, and adding the expanded commercial kitchen and community “700 Dock” taproom. It is very much a family‑run operation, with Kate and her mother Cam commonly mentioned as the day‑to‑day faces of the place.

That rebuilding work was not abstract. A strong storm in 2017 tore up segments of the main dock, which have since been replaced as part of the modernization effort. More recently, a December 2022 king tide flooded the store itself with salt water—high‑water marks are reportedly still visible on an interior post—which neighbors remember as the day the tide “came into the shop.” So while the entire marina has never literally “floated away,” parts of its historic timber infrastructure have been battered and rebuilt after recent extreme events, and both storm and tide damage are now parts of the local lore.

Fireworks are a subject where Boston Harbor’s charm and its worries collide. In the 1990s, with personal fireworks becoming increasingly chaotic and unsafe, the Boston Harbor Association organized a single centralized Independence Day display to cut down on individual mortars and noise; the show grew into a major July 3 event with a kids’ bike parade and a community barbecue.

Over the years the display became so popular that it attracted thousands of visitors by car and boat from outside the neighborhood, bringing congestion, safety concerns, and, in recent years, a sense that the situation had become unmanageable. The Association paused the big show at least once while it considers options for a safer, more controlled celebration, and as of 2024–26 is explicitly “considering solutions to celebrate safely” while still raising sponsorships for a community fireworks event. Historically, the display has been well worth seeing from a boater’s perspective—tight harbor, reflections on the water, neighborhood atmosphere—but anyone arriving now should check the BHA website for that year’s plan and expect an ongoing tension between spectacle and safety.

For fans of the Toliva Shoal Race, Boston Harbor has a specific seasonal role. Toliva is the Southern Sound Series’ third race, a roughly 30–40‑mile winter course starting and ending in Olympia and running north out Budd Inlet through Dana Passage around Toliva Shoal and back. Recent race reports emphasize that the downwind start often gives boats a spirited spinnaker run to Boston Harbor before they harden up for the reach along Dana Passage, and the official 2026 race weekend, for example, is February 13–15, with the start mid‑morning on Saturday.

For a spectator, being at Boston Harbor mid‑ to late‑morning on Toliva Saturday puts you right on the racecourse as fleets stream past, and the docks, beach, and launch area all provide excellent vantage points for photos and for listening to VHF chatter as the fleet compresses at the turn.

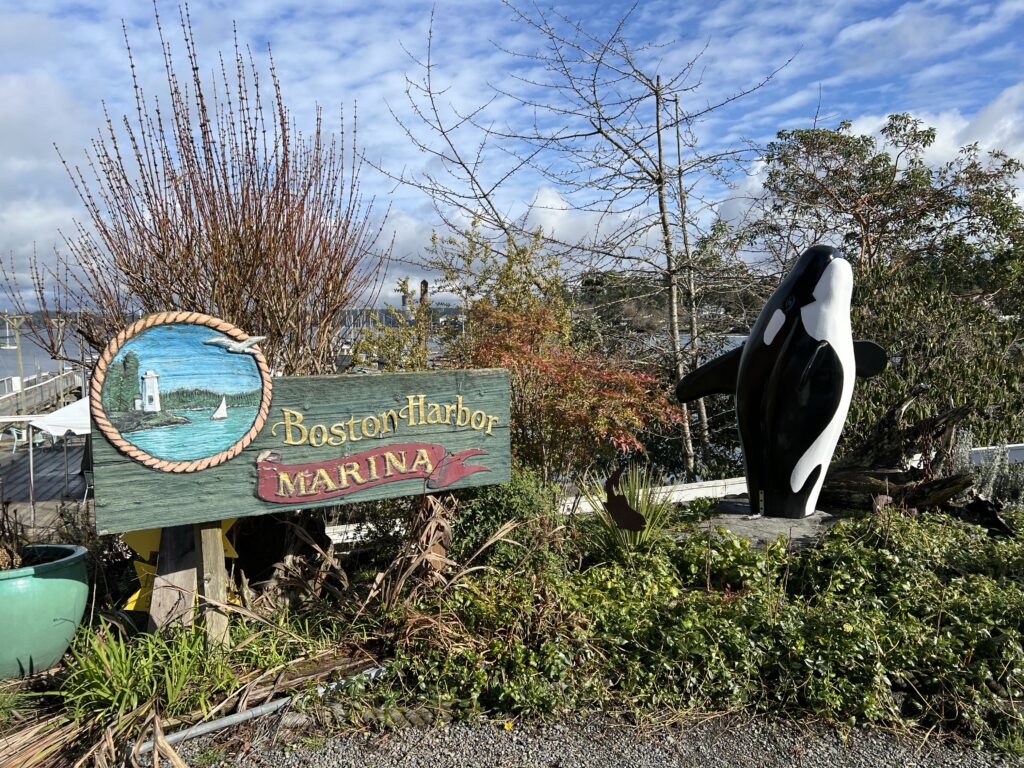

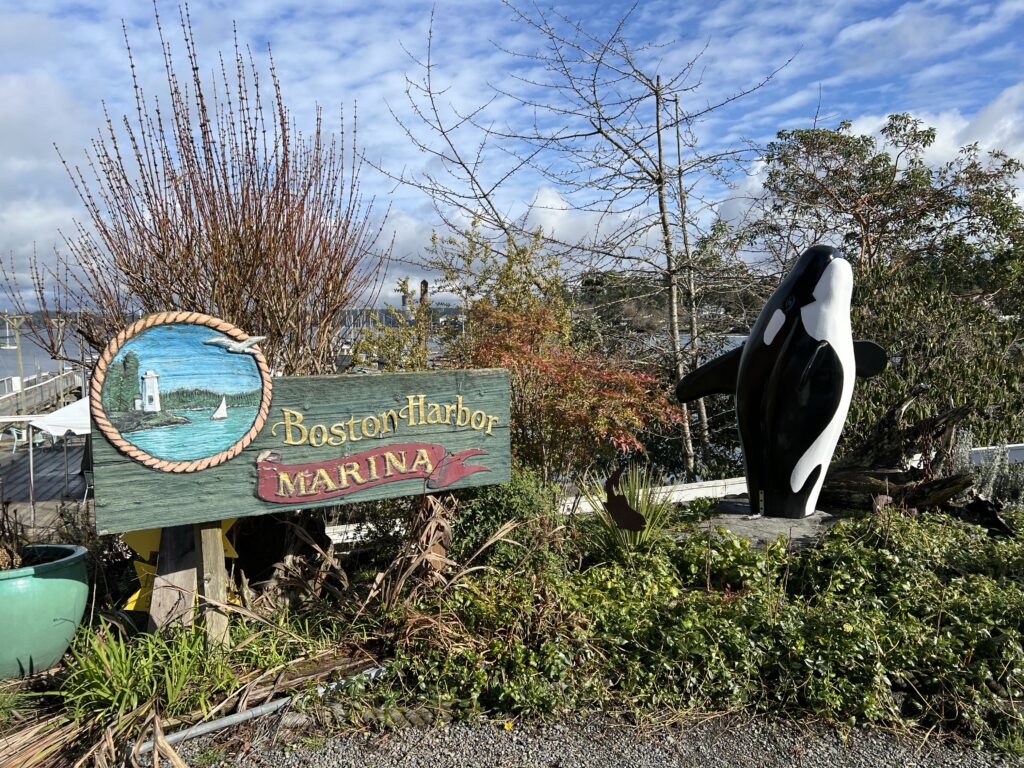

The question about killer whales and pirate statues gets at the harbor’s playful side as much as the ecological one. Southern resident and Bigg’s (transient) orcas do in fact come into South Puget Sound, and recent Orca Network reports include multiple instances of groups transiting past Boston Harbor Marina and Burfoot Park en route into or out of Budd Inlet, generating excited posts from people watching from the docks. Killer‑whale imagery is thus not purely decorative; it celebrates a real, if intermittent, presence.

As for pirate figures, Boston Harbor leans into a lighthearted maritime theme: the area has hosted pirate‑themed marina events, and local listings and reviews refer to a “pirate festival” and pirate styling at the waterfront, so statues and pirate motifs are basically neighborhood whimsy—photo backdrops and mascots that nod to nautical lore rather than any specific historical piracy in Budd Inlet.

All of this leaves the question of when to visit and how the different interests intersect. Summer weekends are ideal for the classic combination of boating, beer, beach, and casual wildlife watching: the snack shack and deck run long hours, Friday‑night music and brewery nights are in full swing, and the likelihood of seeing seals, herons, and eagles from the dock is high.

A negative low tide adds great intertidal exploring for shell hunters and birders, and a winter or early‑spring visit timed to the Toliva Shoal Race turns the harbor into an amphitheater for fleece‑and‑foul‑weather‑gear boat‑watching. If your priority is the heron rookery and broader wildlife, pairing Boston Harbor with a side trip to Woodard Bay NRCA or Billy Frank Jr. Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge gives an outstanding day of South Sound nature, with Boston Harbor Marina as your coffee, chowder, and beer stop on the way back into town.

In short, Boston Harbor is small but unusually dense: a county boat launch and modest moorage; a family‑run marina that does serious food and beer service; a pocket beach useful for both sand‑castles and shelling; a view of an active historic lighthouse; and enough nearby wild shoreline, rookery habitat, and passing whales to keep a naturalist satisfied. For a boater, a beer drinker, a wildlife enthusiast, and a birder, it is one of those rare points on the chart where everyone gets what they came for, often within a hundred yards of the same dock.