Reward

PRIZES FOR NAVIGATION WERE OFFERED by the British Parliament during the 1700s, including the act of 1744 offering a reward for the discovery of a Northwest Passage.

This encouraged Arctic searches from many directions. In 1771, Samuel Hearne, a Hudson’s Bay Company fur trader, ventured to the shores of an ice-choked sea near the mouth of the Coppermine River.

He had reached the waters of the fabled Northwest Passage, 195 years after Martin Frobisher first set out to find it. But Hearne did not know that this was a stretch of the elusive passage.

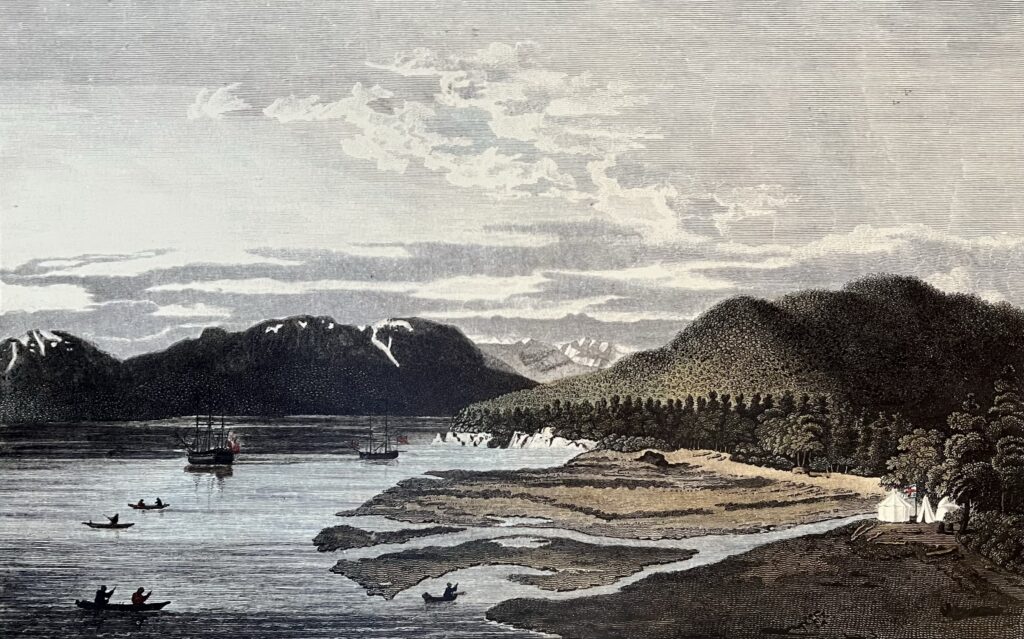

James Cook and George Vancouver’s voyages to the west coast of North America in the late 1700s were in search of the western entrance to the passage. Cook, having been stopped by ice in the Bering Strait, retreated to Hawaii where he was killed and Vancouver’s meticulous survey of the Pacific Coast ended speculation about the existence of an entrance to the Northwest Passage south of the Bering Strait.

The search was placed on hold during the wars with France and the young United States at the turn of the century. It would not be long, however, before a new generation of explorers ventured back into the Arctic.

ONE OF THE GREATEST STORIES OF EXPLORATION and discovery is the European quest for a Northwest Passage – an oceanic shortcut from the Atlantic to the Pacific across the top of North America.

The Vancouver Maritime Museum exhibition chronicles the efforts of the European explorers from Martin Frobisher to the fated 1845 expedition of Sir John Franklin when every single crewmember perished in the Arctic.

The searches for the lost Franklin expedition resulted in the mapping of a Northwest Passage and much of what would become Canada.

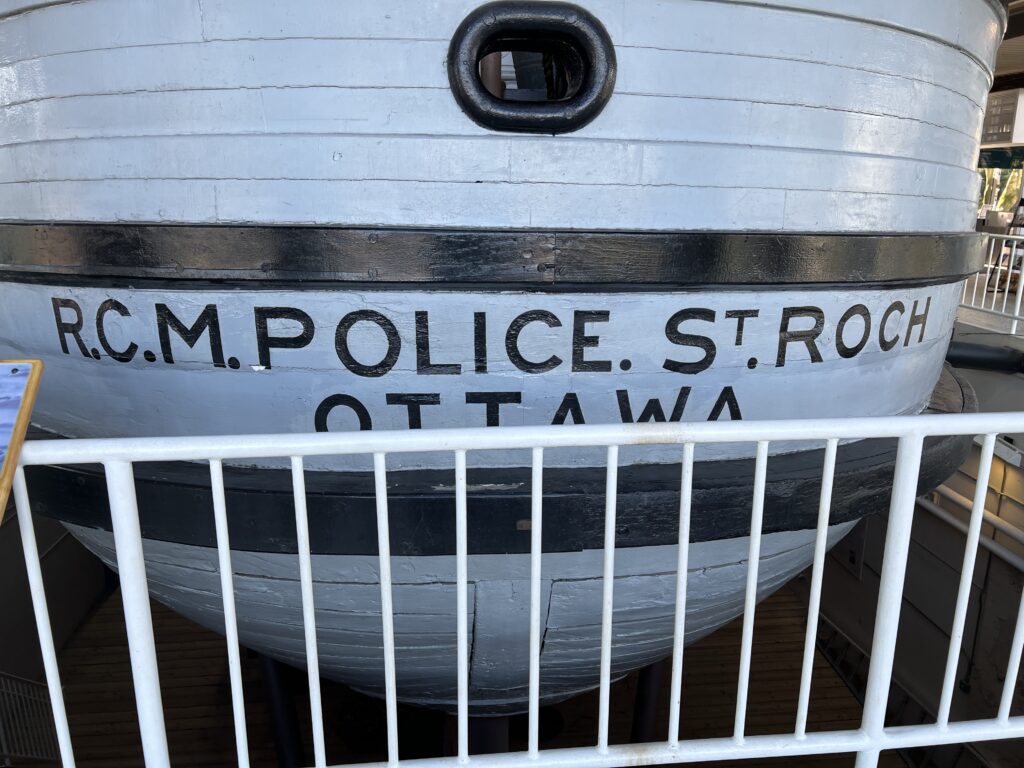

2026 Exposition under the St Ross

A successful crossing through the passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific was first completed during the 1903-1906 voyage of Roald Amundsen. Canada’s RCMP schooner St. Roch, also completed the passage, becoming the first vessel to journey from west to east.

The discovery of Franklin’s ship HMS Erebus by Parks Canada has now opened new opportunities to interpret one of the biggest mysteries in maritime history.

ADVENTURER, PIRATE, AND MASTER MARINER

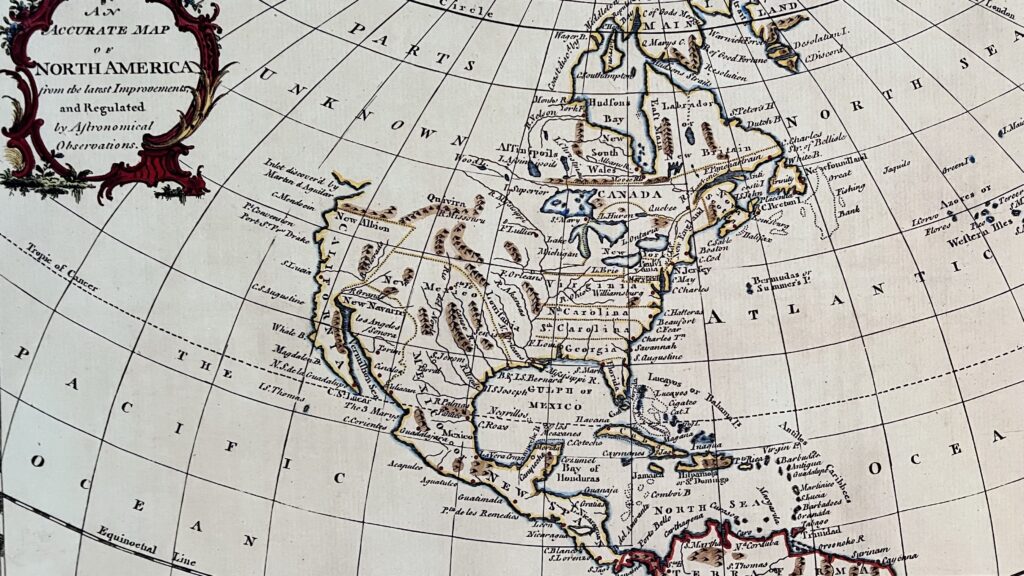

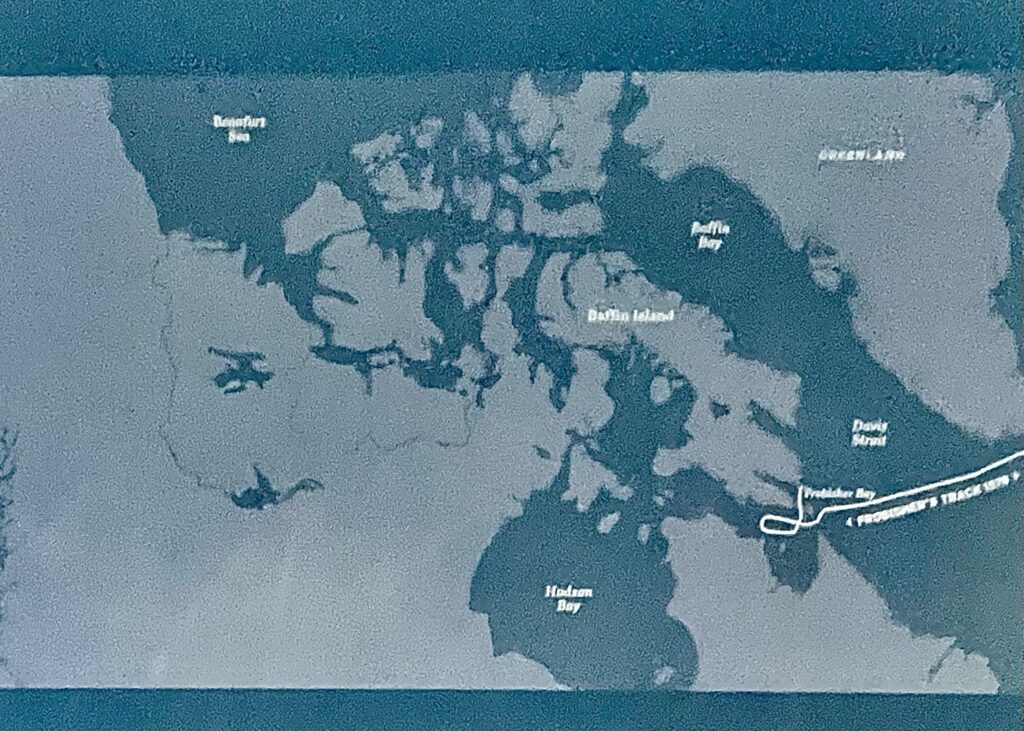

Martin Frobisher made one of the earliest attempts to find the Northwest Passage. Between 1576 and 1578 Frobisher made three voyages into the Arctic, but found only dead-ends and disappointment. The first expedition failed to reveal a passage through the Arctic but Frobisher returned to England with a shiny substance, “black ore,” believed to be gold.

Any thought of finding the Northwest Passage was abandoned on the subsequent voyage, which focused solely on mining “black ore.” Frobisher led a final massive Arctic expedition of 397 men, which saw 1,300 tons of black ore loaded on to 15 ships. Every single ounce of it proved to be worthless iron pyrite (fool’s gold).

Frobisher’s encounters with the Inuit were just as catastrophic. During the first voyage the English traded bells, knives, looking glasses, and other trinkets with the Inuit, who provided meat, fish, seal, and bearskin coats. Tensions between the two cultures boiled over during the second voyage and the English attacked. The Inuit, unable to prevail against the European firearms and steel-tipped arrows, chose to drown themselves rather than be captured. Six Inuit were killed, and three Englishmen were injured.

DAVIS STRAIT, HUDSON’S BAY, BAFFIN ISLAND.

These and many more familiar geographic locations in the Canadian north are named for the early explorers who charted the Arctic labyrinth, searching for a passage to the Pacific. After Frobisher’s “black ore” debacle, a series of expeditions set out near the beginning of the 16oos to pick up the quest he had abandoned. None were successful and many lives were claimed by the harsh environment.

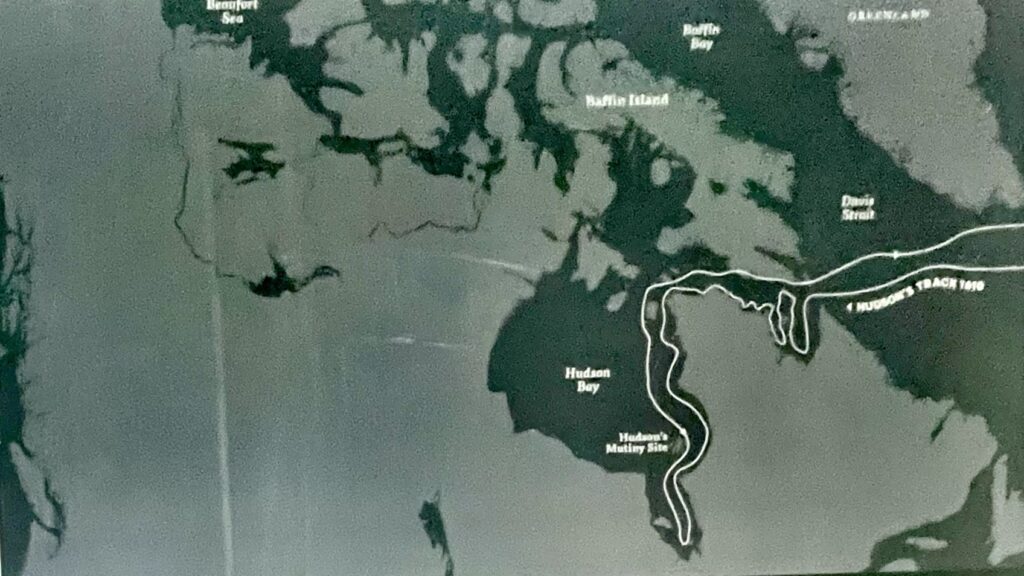

In 1611, after entering the bay that holds his name, Henry Hudson’s crew mutinied, setting him adrift on the water with his son and sick crewmembers.

Jens Munk, a Danish explorer, battled scurvy and disease while wintering off Hudson’s Bay in 1619-20. Of his 64-man crew, only he and two others survived to return home.

Despite failing to find a passage through the Arctic, Hudson, Munk and dozens of subsequent explorers added their own piece to the puzzle that would aid future attempts. Hudson’s voyages also introduced the strategically placed bay, leading to the establishment of trading posts and the creation of the Hudson’s Bay Company.

CONCERN THAT ANOTHER NATION might “discover” the passage first, the British government revived Britain’s search in 1818, dispatching John Ross, W. Edward Parry, David Buchan, and John Franklin. Buchan and Franklin explored the east coast of Greenland, while Ross and Parry took the west coast in order to sail through Davis Strait.

Buchan and Franklin were stopped by ice off the coast of Svalbard and returned home. Ross, having sailed west from Davis Strait into Lancaster Sound, turned back claiming he saw a mountain range blocking this route. His officers later swore that Ross alone had seen the mountains. All of Ross’s previous achievements were ridiculed and his description of mountains blocking his way was called “a pitiable excuse for running away home.” This was the worst mistake of Ross’s career, and haunted him to the end of his life.

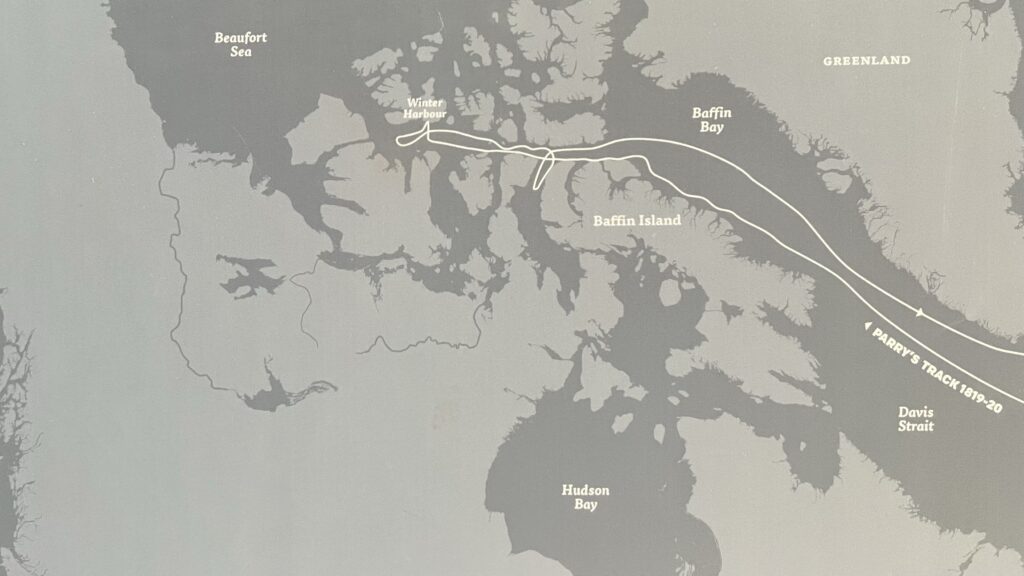

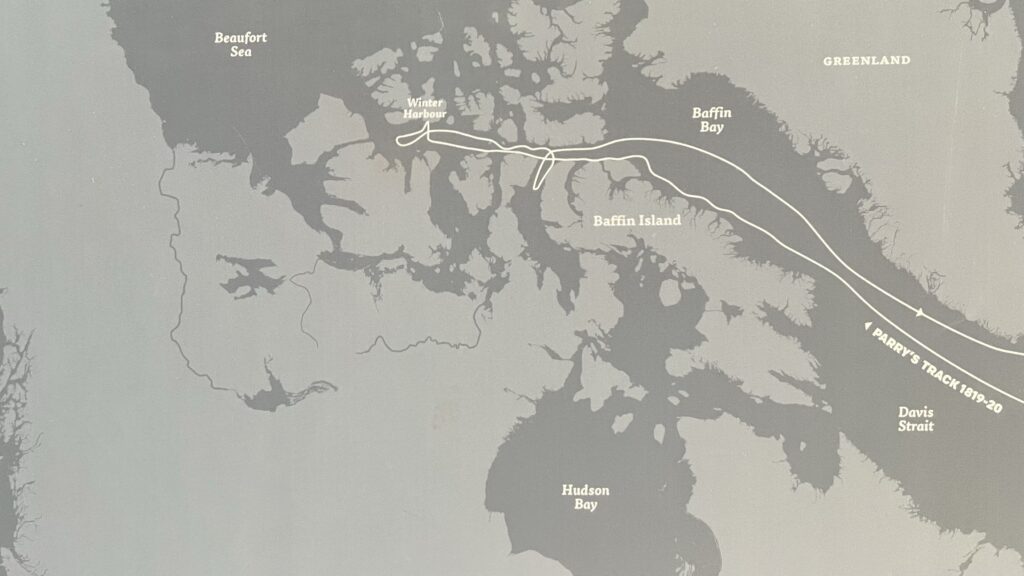

FOLLOWING JOHN ROSS’ HUMILIATING RETREAT from the Arctic, W. Edward Parry succeeded where Ross had failed, setting new navigational records. In 1819 Parry sailed into Lancaster Sound, past the imaginary line of mountains seen by Ross. On September 4 the ships Hecla and Griper passed 110° west and were now halfway through the Northwest Passage. Parliament had promised a £5,000 reward for this feat, so Parry named the nearest promontory Cape Bounty in honour of the occasion.

Ice stopped their progress at 112° 51′ west longitude and Parry’s ships were anchored in a cove he named Winter Harbour.

Over the winter, Parry kept morale high and his crew healthy by growing plants and organizing active theatrical productions in which even he took part.

Before sailing home, Parry carved an inscription in a massive sandstone boulder. The monument marks the westernmost point reached by Parry. He had concluded one of the most successful voyages in the history of the quest for the Northwest Passage. The expedition ended without loss of life, opened the first leg of the passage and pushed 600 miles west.

Decades would pass before a ship sailing from the east reached as far.

While EDWARD PARRY WAS ENCOUNTERING hardships in 1819, the Admiralty sent Franklin by land to the Coppermine River mouth to chart the coast of the Arctic Ocean.

In all, Franklin and his men mapped 550 miles of coast but the lack of food became a serious problem. Forced to turn back, the expedition hoped to reach Fort Enterprise before starvation, sickness, or winter claimed their lives. To survive, the men began scraping lichen off the rocks and boiling it, or on other occasions, eating their old shoes. One of Franklin’s men, Robert Hood, was stricken with dysentery and another, having slowly gone insane, shot Hood in the back of the head.

A group, led by George Back, was sent ahead to Fort Enterprise, but when Franklin arrived the fort was empty. A note left by Back said he had followed some Natives south in search of food. Franklin and his men remained at the fort, clinging to life. Back returned with food and the expedition rebuilt their strength over the winter, before starting east.

They arrived at York Factory, Manitoba, on July 14, 1822. Over land and water, they had traveled some 5,500 miles, and an even longer journey into the darkest depths of despair ever found in the human heart.

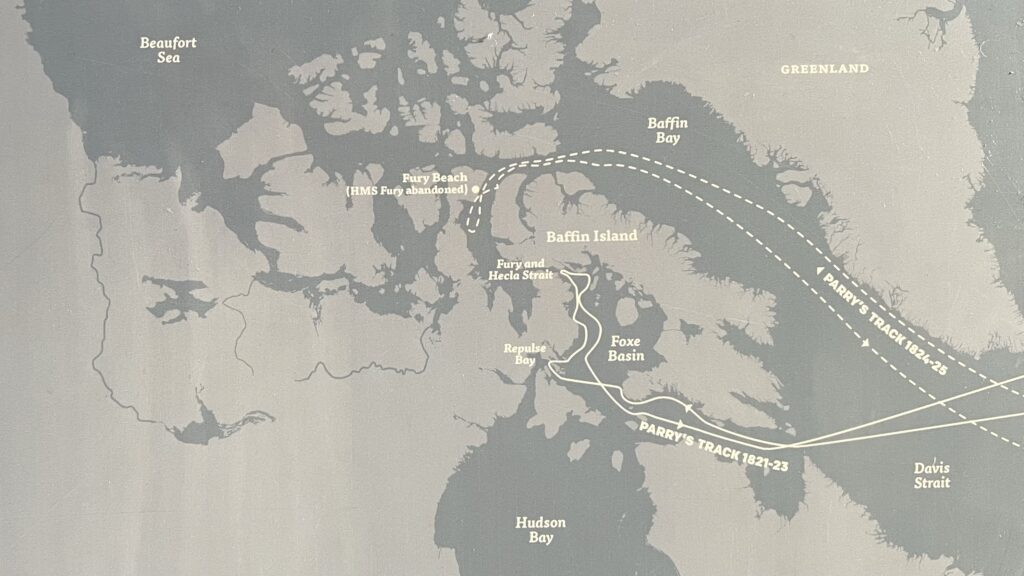

IN 1821 PARRY’S SECOND VOYAGE brought him closer to the local arctic inhabitants, and closer to finding a Northwest Passage. Parry sailed his ships Hecla and Fury into Repulse Bay for the winter and over the next three months he worked with local Inuit to create maps of the area. The maps led Parry to a body of water he named Fury and Hecla Strait, but ice prevented him from entering. After deciding they might not last a third winter, Parry turned for home. From the tantalizing glimpses so far, it seemed clear that a Northwest Passage could be found with enough men and ships to enter the Arctic from a number of directions.

Parry’s 1821–1823 voyage in Hecla and Fury did not find a navigable Northwest Passage, but it produced several important geographic and scientific results and helped refine Arctic wintering practices.

Geographic outcomes

- He showed that no passage existed through Repulse Bay or immediately along the north coast of the Melville Peninsula, closing off one hoped‑for southern route from the north‑west corner of Hudson Bay.

- The expedition reached and examined what is now called Fury and Hecla Strait, confirming that a channel existed toward the west but that it was normally choked with ice and unnavigable for sailing ships at the time.

- Combined with Franklin’s overland work, Parry’s voyage helped narrow the remaining “unknown gap” of the Northwest Passage to a smaller area between the Coppermine/Back River region and Repulse Bay, focusing later searches.

Scientific and practical outcomes

- Parry’s party collected significant data on the Earth’s magnetism and Arctic wildlife, contributing to early 19th‑century geophysics and natural history.

- The expedition successfully overwintered twice in the Arctic, refining methods of ship insulation, heating, diet, and crew routine that became a model for later British polar expeditions, including Franklin’s.

Strategic significance

- Even without a through‑passage, the voyage added detailed mapping of coasts and channels in Foxe Basin and around the Melville Peninsula, filling key blanks on Admiralty charts.

- Its results reinforced the idea that the Northwest Passage existed but was blocked by persistent ice in narrow straits, shaping British strategy and expectations for the next generation of expeditions.

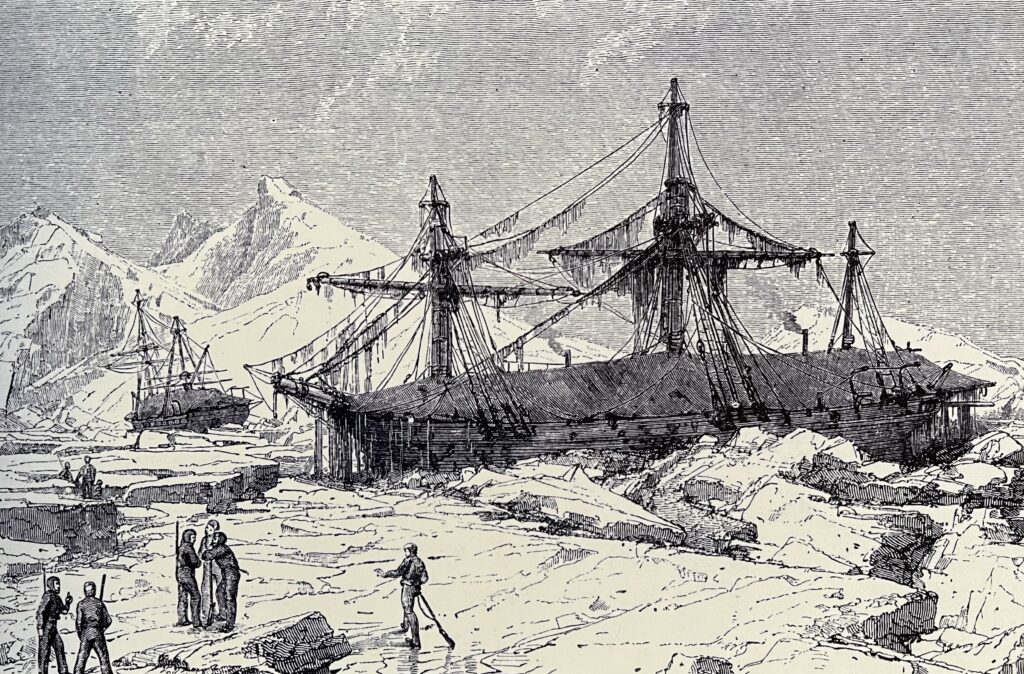

Encouraged by the observations of his previous voyage, Parry launched a third expedition in 1824, intended to meet the concurrent expeditions of Franklin and Beechey. Poor ice conditions through Lancaster Sound took their toll and Fury was irreparably damaged in July of 1825. With Fury abandoned, any thoughts of pressing on were forgotten, and the crowded Hecla returned to Britain in November.

Parry’s 1824–1825 voyage with Hecla and Fury is usually described as his least successful Northwest Passage attempt, but it still had some important consequences.

Immediate outcomes

- The expedition aimed to push south through Prince Regent Inlet to find a new route, but heavy, shifting pack ice in Baffin Bay and Lancaster Sound badly delayed them.

- They were forced to winter in Prince Regent Inlet, and when the ice partially cleared, Parry tried to work along the west side of the inlet looking for an opening, but dense floes blocked further progress.

- The ship Fury was driven ashore and fatally damaged by ice pressure near what is now Fury Beach on Somerset Island; after failed repair attempts, she was abandoned with most of her stores, and the whole party crowded into Hecla.

- With one ship and two crews, Parry had to abandon the attempt and return to England, despite believing he could see open water to the south, effectively ending his career of Northwest Passage exploration.

Scientific and later practical outcomes

- Even on this failed voyage, the expedition continued collecting data on magnetism and Arctic wildlife, adding to the Admiralty’s growing body of polar scientific observations.

- The abandoned stores at Fury Beach later proved crucial: when James Clark Ross reached the area years afterward, the cached provisions and equipment from Fury were invaluable for sustaining his own expedition, turning a past disaster into a logistical asset for later explorers.

In sum, Parry’s 1824–1825 expedition did not advance the navigable Northwest Passage and cost the Royal Navy a specialized polar ship, but it still contributed charts, scientific data, and a supply depot that helped subsequent Arctic voyages.

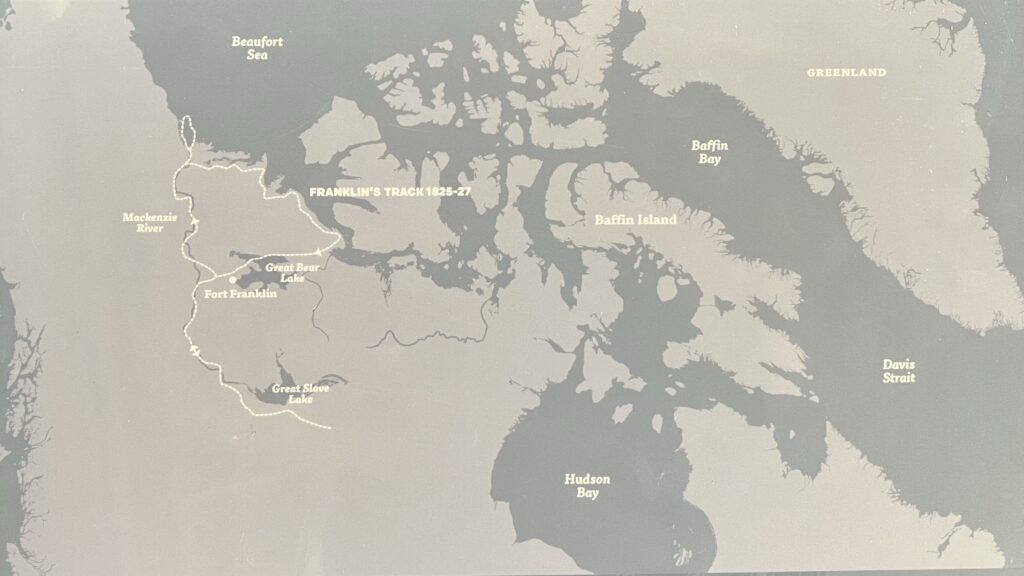

FRANKLIN’S NEXT VOYAGE WAS PART of a well-planned, four pronged assault on the Arctic, including expeditions led by George Lyon, Frederick Beechey and, as we have seen, Edward Parry. After sailing to New York in 1825, Franklin’s expedition once again traveled to the Arctic coast, this time at the mouth of the Mackenzie River. There the group split in two: one traveled west to meet Frederick Beechey who had sailed through the Bering Strait, the other went east to chart the coast towards the Coppermine River.

Rowing, sailing, and at times wading through the icy waters, Franklin’s men worked their way up the coast toward Alaska.

Weather and ice forced Franklin to turn back, at a spot he named Return Reef. He was only 160 ice-blocked miles from Point Barrow, where Beechey was waiting. When Beechey left on August 26, he was not aware of how close he and Franklin had come to meeting. But Franklin was wise to retreat, as storms and heavy surf nearly wrecked Beechey’s ship on the return journey. The efforts of Franklin’s expedition had resulted in 1,500 miles of newly charted coastline, which considerably expanded Britain’s understanding of the passage.

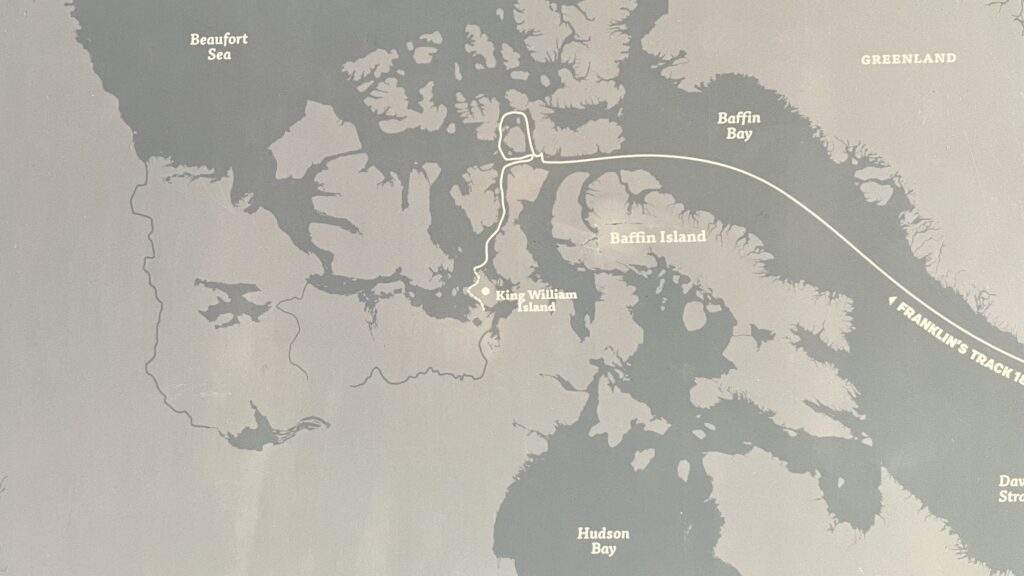

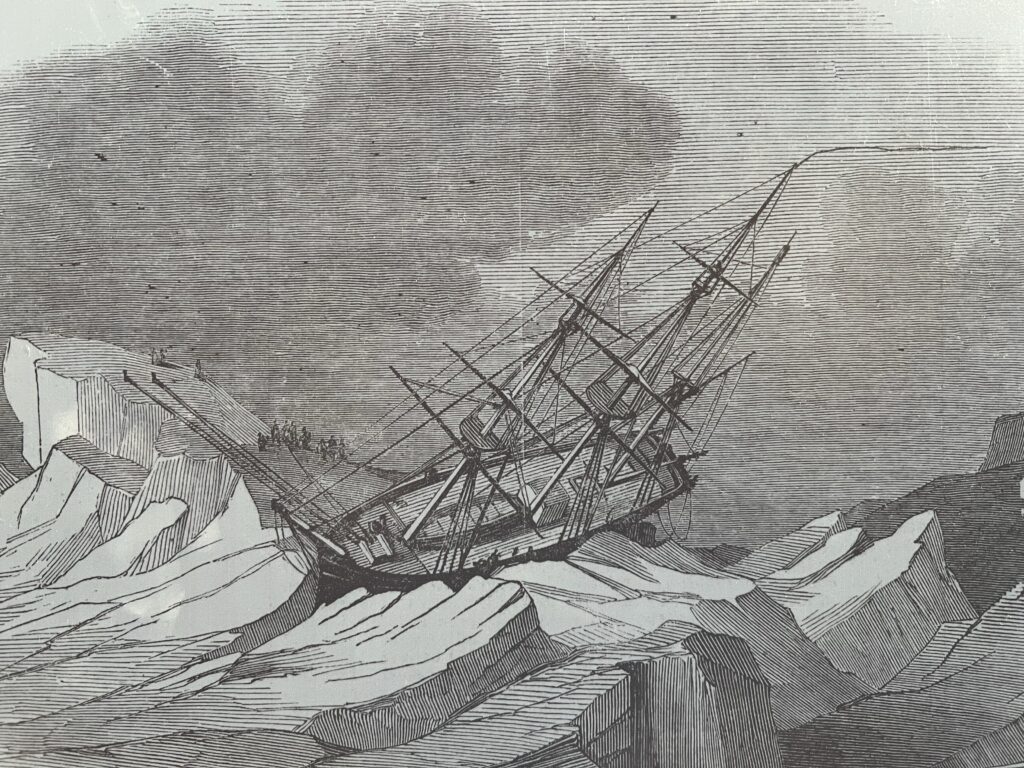

CONVINCED THAT A NORTHWEST PASSAGE through the ice-filled maze of the Arctic archipelago was possible, the Admiralty dispatched the ships HMS Erebus and Terror with Sir John Franklin in command. His instructions were to proceed through Lancaster Sound and Barrow Strait toward the place where Parry had been stopped by the ice twenty-five years earlier. The Royal Navy placed 134 officers and men under Franklin. Erebus and Terror were outfitted with steam engines and propellers, large libraries, scientific instruments, hand organs for musical performances, and were provisioned with supplies for a three-year voyage. Indeed, it seemed, nothing could go wrong.

On the morning of May 19, 1845, Erebus and Terror weighed anchor and sailed from the Thames to rendezvous with a supply ship off the Greenland coast. Six men, deemed unfit to continue, returned to Britain with the last letters to be sent from the expedition. Franklin, writing to Parry, reported that the weather had been fine: “I think it must be favourable for the opening of the ice.” On July 28, Erebus and Terror met the whalers Enterprise and Prince of Wales in Baffin Bay while waiting for favourable conditions to enter Lancaster Sound.

After their brief sojourn with the whalers, Erebus and Terror continued on to their destiny. The Arctic closed around them, and they vanished.

A letter to the ADMIRALTY in September 1846 from John Ross pointed out that Franklin and his men should have reached the Bearing Strait if the mission had been successful.

Slow to respond, the Admiralty sent James Clark Ross with HMS Enterprise and Investigator on a rescue mission to the eastern Arctic in 1848. Additionally, the Admiralty dispatched HMS Plover and Herald to the western Arctic, commanded by Thomas Edward Laws Moore and Captain Henry Kellett.

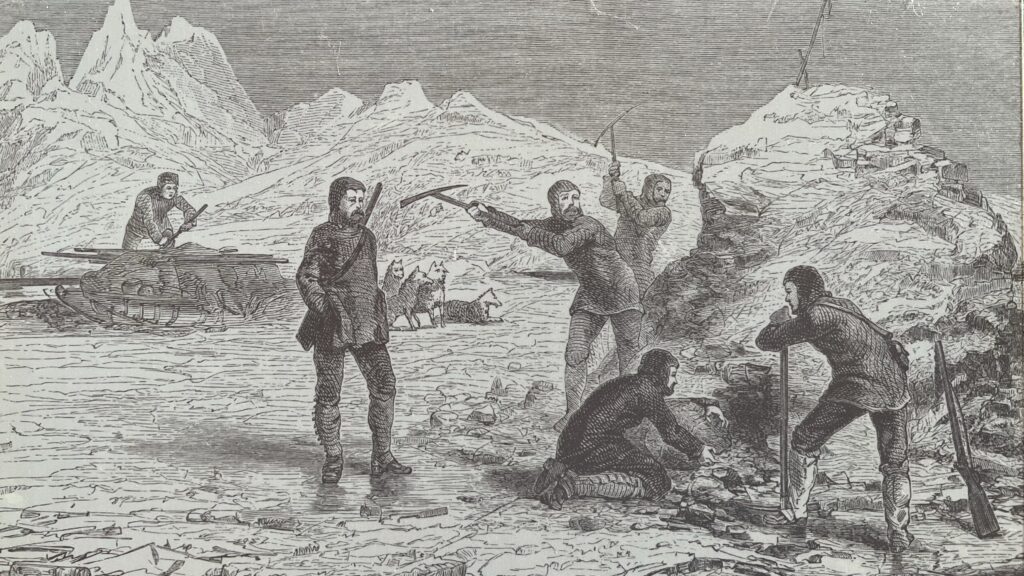

Ross searched the coasts of the Arctic islands with sledge crews. He trapped and released Arctic foxes after tagging them with specially engraved metal collars, hoping that the message would alert Franklin’s crews to the presence of rescue ships. The Admiralty sent a third search party, this one by land, to follow his and Franklin’s old overland track to the Coppermine River through 1848. Ultimately, however, all the expeditions failed to find any trace of Franklin or his ships.

IN 1853, DR. JOHN RAE WAS DISPATCHED from the Hudson’s Bay Company to search for Franklin. Local Inuit told Rae of a company of men seen dragging sleds over land in search of food and all of the men were looking thin.

Catholic moral tradition distinguishes between killing for food(always murder, gravely sinful) and eating flesh from an already dead body in extreme necessity, like starvation where no other food exists. Historical theologians, including the Salamancan school, held that cannibalism of the dead is permissible then as a “regrettable least-worst choice,” contrary to natural appetite but not intrinsically evil—much like using human tissues for transplants in dire situations.

Magisterium AI

Another group of Inuit informed Dr. Rae that they had discovered thirty corpses, as well as graves at a makeshift camp. In words that shocked and horrified readers back in Victorian Britain, Rae reported that “from the mutilated state of many of the bodies, and the contents of the kettles, it is evident that our wretched countrymen had been driven to the last dread alternative as a means of sustaining life.”

Rae had no doubt that the Inuit reports were about the men from the lost Franklin expedition, and purchased items that the Inuit had collected from the bodies, including silverware marked with the initials of Franklin, Crozier, and ten other officers from Erebus and Terror. From Rae’s reports, it appeared that the Franklin expedition had met with disaster somewhere in the vicinity of King William Island. Many Britons, however, including Lady Franklin, chose not to believe Rae’s account of cannibalism and encouraged other searchers to seek further evidence.

FIVE YEARS AFTER THE DEPARTURE of Franklin’s final voyage, Horatio Austin’s search expedition aboard HMS Assistance came upon the first traces of the gruesome end for the crews of Erebus and Terror.

At Cape Riley on Devon Island, they discovered a temporary camp and on the shores of Beechey Island the search party discovered foundations of three temporary buildings, two cairns and the graves of three of Franklin’s crew. The three graves, marked by wooden headboards, held the bodies of John Torrington, John Hartnell, and William Braine.

A pike pole stuck into the shore, with a small painted hand pointing toward the water, aroused considerable speculation. Was it a marker indicating where the expedition had gone? The searchers concluded it had been setup to guide shore parties back across the snow and ice to Erebus and Terror.

Three out of 129 men were now accounted for, but where was the rest of the vanished expedition?

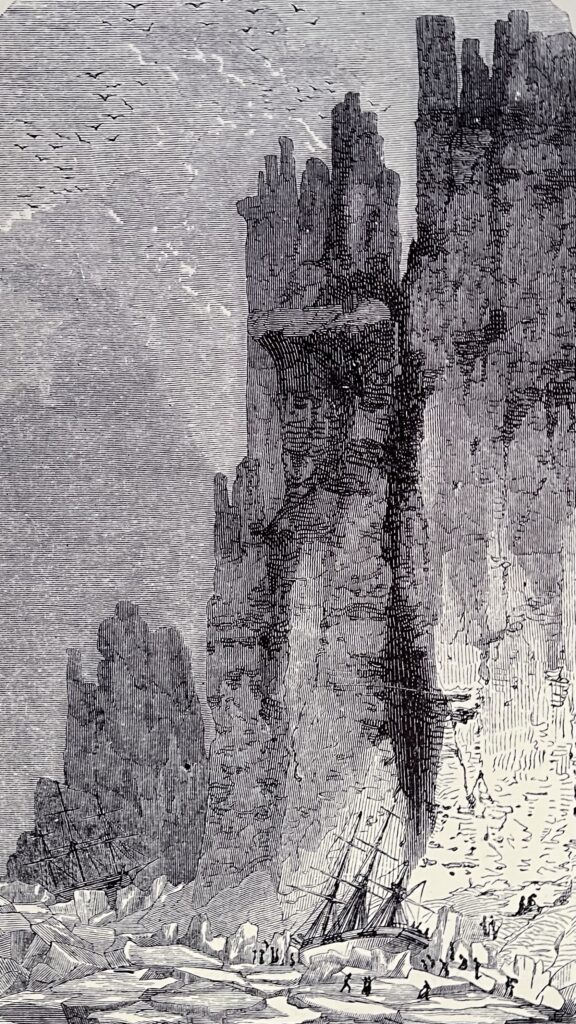

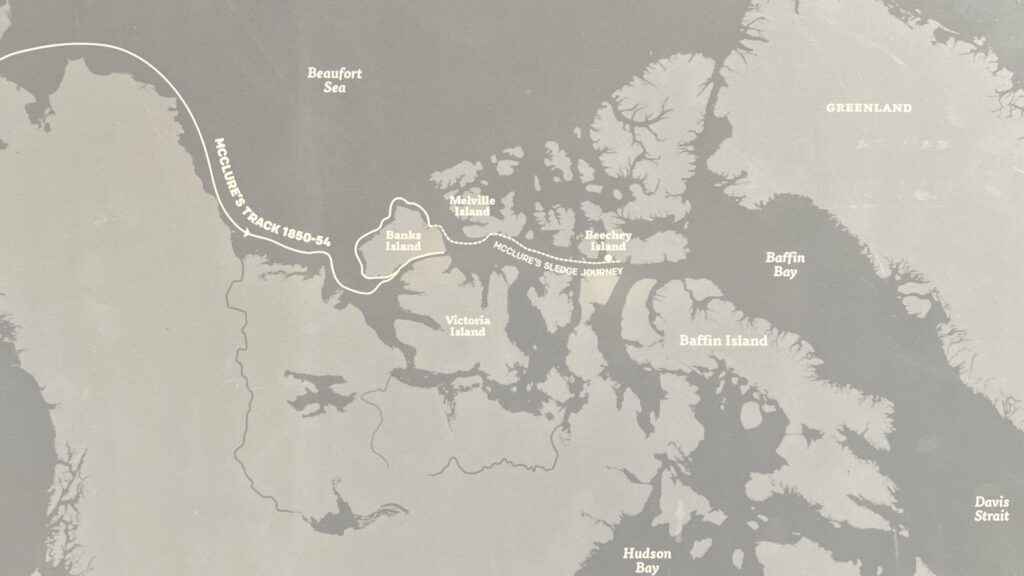

WHILE EXPEDITIONS TO THE EASTERN ARCTIC had found traces of Franklin, Captain Richard Collinson in Enterprise and Robert McClure in Investigator were dispatched to search from the western Arctic.

When Investigator reached Bering Strait at the end of July, 1850, there was no news of Collinson. Instead of waiting for his superior officer, McClure pushed ahead and sailed Investigator up Prince of Wales Strait, between Banks and Victoria Islands. The ice began to thicken and within a few days, the ship was frozen in pack ice. Being only 30 miles from Barrow Strait, McClure took a chance and let the ship drift east instead of trying to free the ship and turn back.

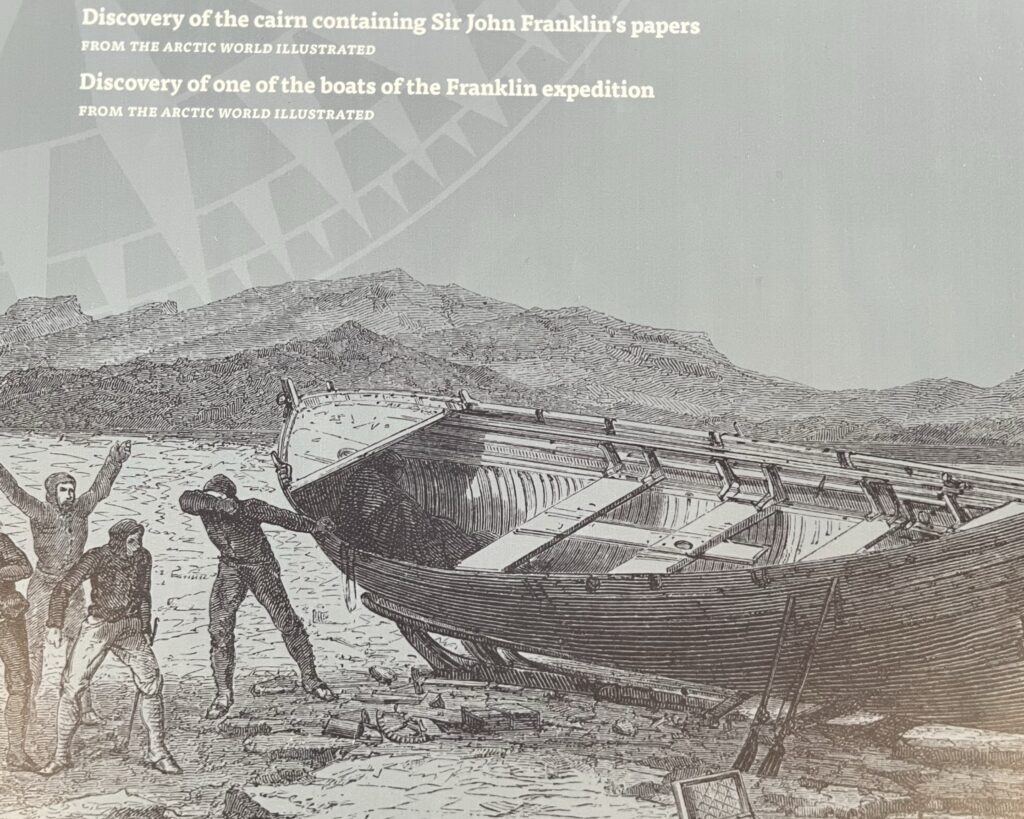

Over the winter, small sledge parties explored the surrounding country. By the end of October, they had reached the northern end of the strait. Johann Miertshing, the ship’s interpreter, wrote in his diary that they stood “at the east end of the land Captain Parry had sighted thirty years before from Melville Island… so the problem of the Northwest Passage, disputed for 300 years, was solved.” Upon their return to England in 1854, McClure and his crew were rewarded for their discovery of “a Northwest Passage.”

WITH THE NORTHWEST PASSAGE NOW MAPPED, all that remained was Lady Franklin’s determination to learn her husband’s fate. Francis Leopold McClintock and George Hobson’s search in 1858-9 uncovered a cairn on King William Island with a note from 1848 that listed the growing number of dead, including Franklin himself. They also found an abandoned ship’s boat containing supplies and the skeletons of two men. This confirmed John Rae’s reports that the expedition had met with disaster and augmented the older Inuit accounts with new ones about men who “dropped by the way.”

Further searches were carried out by Americans Charles Francis Hall in the 1860s and Lieutenant Frederick Schwatka in the 1870s. While other artifacts and remains were found over the course of the next century, the wrecks themselves, the grave of Franklin, and cached records from the lost expedition remained elusive. However, the allure of the fog-shrouded coast and the dream of sailing a ship all the way through the Northwest Passage remained strong.

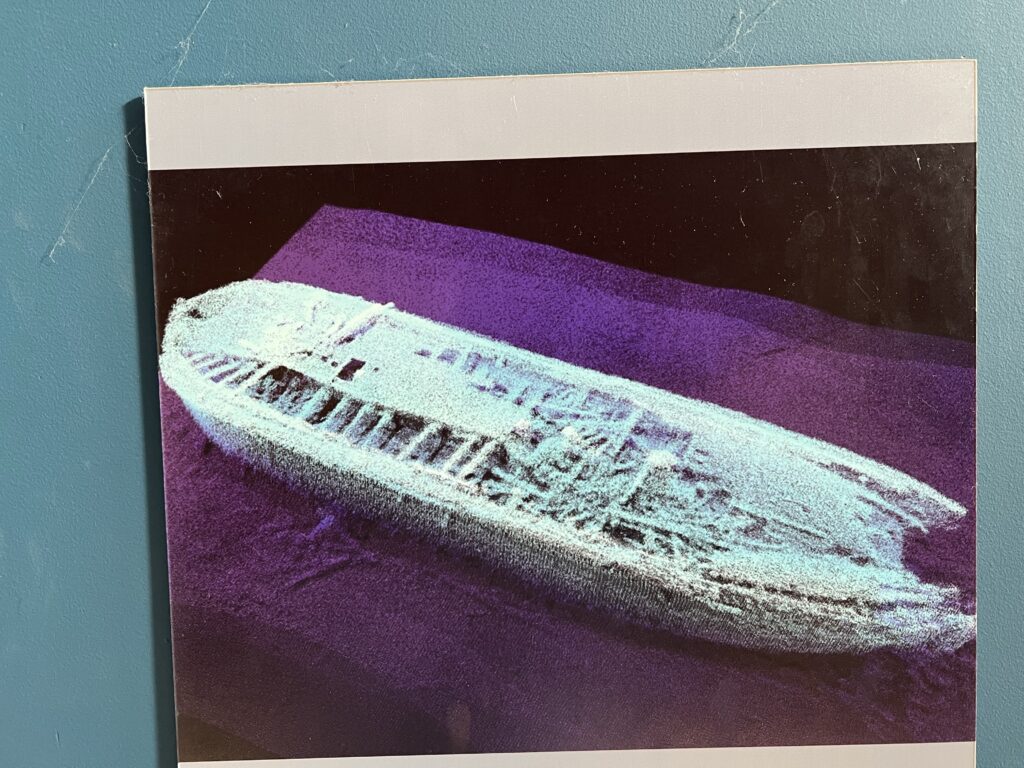

EARLY IN SEPTEMBER 2014, the ghostly outline of a ship appeared on the sonar of the Parks Canada dive vessel Investigator. On October 1, it was announced that the ship was Franklin’s lost HMS Erebus, signifying a breakthrough in one of Canada’s longest standing mysteries.

Ryan Harris of Parks Canada led the 2014 Victoria Strait Expedition, a combined effort among multiple government and non-government agencies. It was the most ambitious search for the lost Franklin ships to date and employed world-class sunken-wreck-finding technology. In addition to the sonar already mentioned, the Canadian-made Autonomous Underwater Vehicle (AUV) Arctic Explorer was deployed under the Arctic ice to take high-resolution scans of the seabed.

Perhaps one of the most integral sources of information that led to the discovery was the contribution of Inuit oral history expert Louie Kamookak. Inuit oral history identified Umiaqtalik, “the old ship place”, in the southern Queen Maud Gulf, as the location of an abandoned Franklin ship.

This knowledge, combined with European accounts, helped Parks Canada hone its survey to an area west of the Adelaide Peninsula. The six year survey finally proved fruitful, but this was only the beginning.

IT IS FITTING THAT Ryan Harris and Jonathan Moore, Parks Canada senior underwater archaeologists, were the ones to first spot the outline of a lost Franklin ship. They have been a part of the renewed search for the lost ships since it began in 2008 and spent countless hours in the wheelhouse of Investigator staring at their sonar screen.

When the outline of HMS Erebus was recorded by the towed side-scan sonar, Marc-André Bernier, chief of Parks Canada’s underwater archaeology team was brought over to Investigator from CCGS Sir Wilfrid Laurier to confirm the find.

A Remotely Operated Vehicle brought back the first high-definition video footage of the historical discovery, which showed a remarkably well-preserved shipwreck sitting in 11 metres of water.

Harris and Moore became the first to dive the wreck, quickly followed by other members of the Parks Canada underwater archaeology team. Photographs, video and measurements captured on these dives confirmed that this ship was the lost HMS Erebus.

SIGNIFICANCE OF THE FIND

BESIDES SOLVING A CENTURIES OLD MYSTERY, discovering HIMS Erebus has brought greater attention to the Arctic and its importance. The establishment of permanent Arctic research stations will help us to better understand this fragile ecosystem and our impact upon it. Social and economic developments that are planned for Arctic communities, such as a dedicated artist’s studio in Cambridge Bay and an Arctic deep-water port, will benefit from the interest in the Arctic that the recent Erebus discovery has created

Inuit oral histories became an invaluable asset for the archaeological team during the 2014 search. Future archaeological surveys in this area will therefore continue to place importance on the oral histories of the Inuit.

The scores of voyages during the 400-year quest for a Northwest Passage helped to chart and define the land that would eventually become Canada; they are as much a part of Canadian history as the histories of the nations who first sought the passage. With the exciting discovery of Erebus, the opportunity to engage all Canadians with the history and culture of the Arctic has presented itself. This event reminds us that despite our geographical separations, we share a storied past that has shaped who we are as a people.

THE FABLED NORTHWEST PASSAGE, so many centuries in the finding, proved neither a fast road to the riches of the Orient nor an easy route for the explorer seeking fame. It traverses a difficult land, a land that is currently experiencing great change. The natural resources of the Arctic are spurring new development. The Inuit, who have lived here longer than anyone, have seen their cultures and lifestyles affected by the influx of Europeans to North America. Yet they survive, and in 1999, with the Canadian government’s decision to create the semi-autonomous region of Nunavut, they gained back a measure of self-government and a reassertion that these are their lands.

For all the triumph and tragedy that has transpired, the Northwest Passage through the Arctic will be remembered as one of the great landmarks of the human ambition. And the discovery of Franklin’s lost ship shows that the Arctic still has many secrets to reveal.