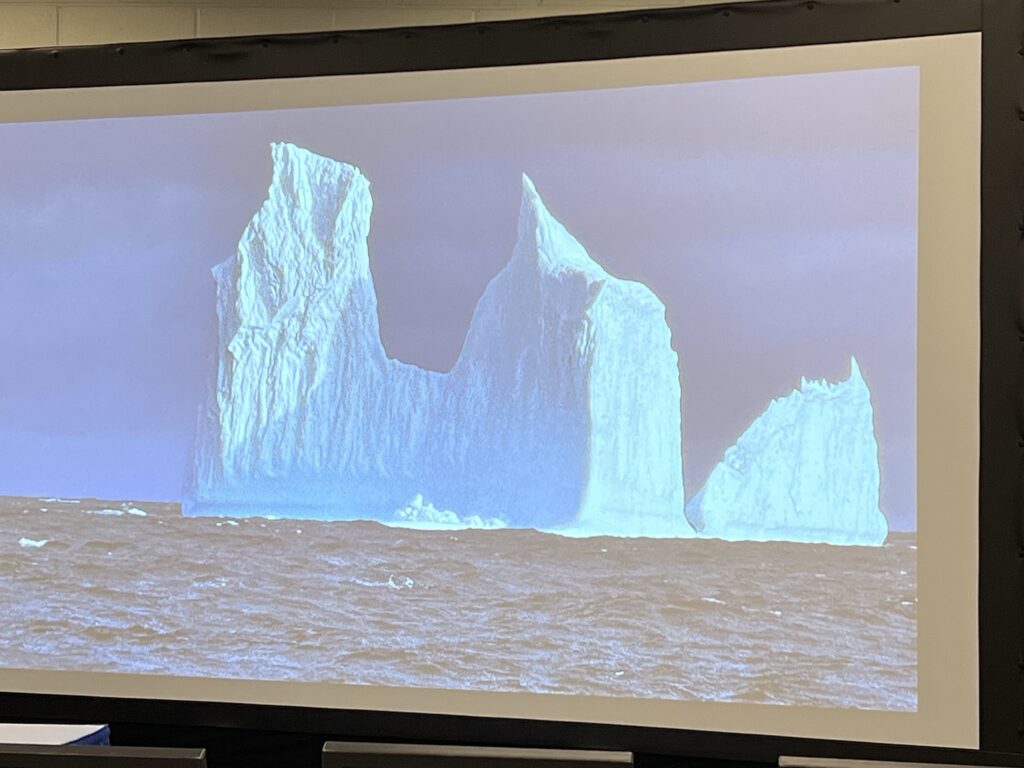

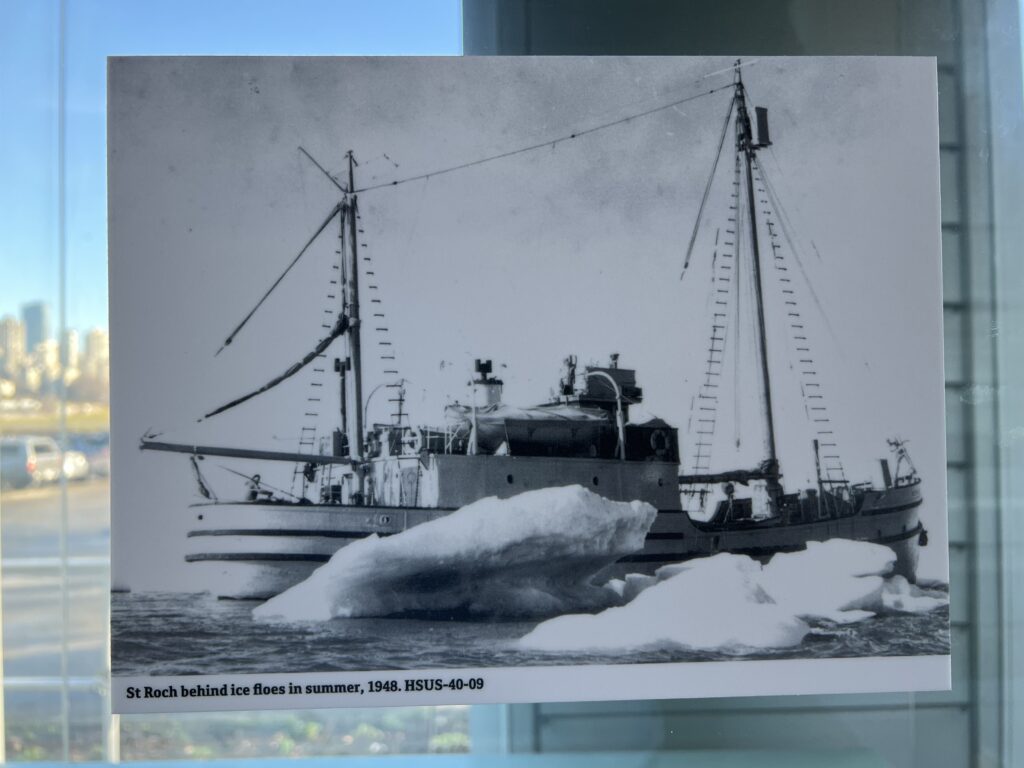

St. Roch is an ice‑capable wooden schooner with the following characteristics and record‑setting voyages:

- hull form: heavy scantlings, reinforced bow, and the pragmatic compromises of designing a supply and patrol vessel for icebound waters in the 1920s.

- first west‑to‑east traverse of the Northwest Passage (1940–42),

- first to complete the Passage in a single season (1944)

- first ship to circumnavigate North America (finished 1954 via Panama).

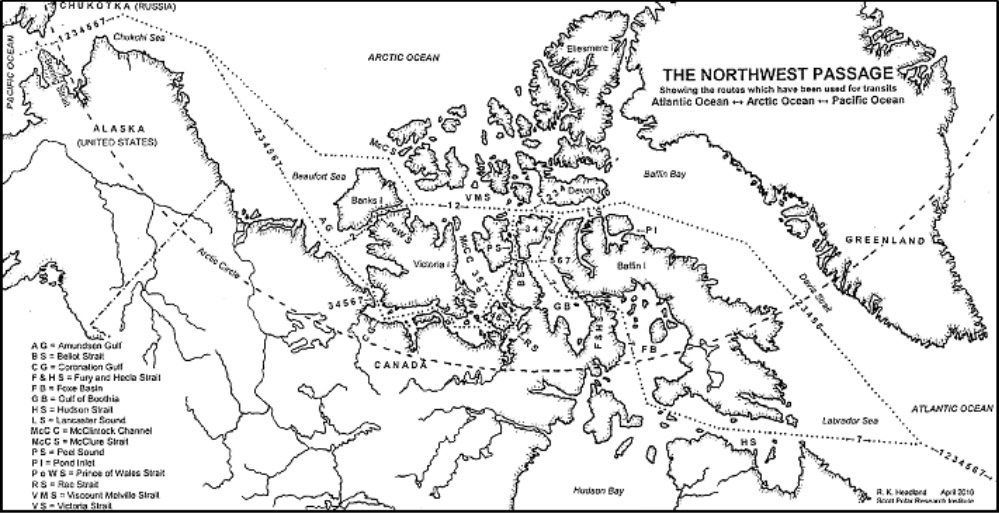

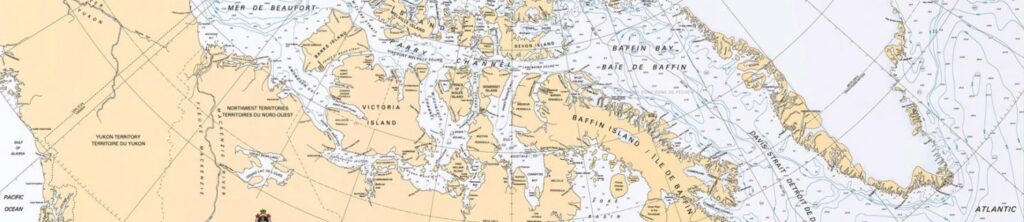

By way of background, Roald Amundsen’s 1903–1906 voyage in the little sloop Gjøa was the first complete transit of the Northwest Passage, achieved by going small, staying close to the coast, and learning from the Inuit rather than trying to overpower the Arctic. She did this going east to west.

Gjøa was a small, wooden, former herring/fishing sloop of about 45–47 tons, shallow draft, and fitted with a modest paraffin engine of around 13 horsepower. Amundsen deliberately chose a vessel much smaller than the big, heavily manned naval expeditions, reasoning that a tiny crew could live off local resources and maneuver through narrow, shallow channels that would trap larger ships. He bought and refitted Gjøa in 1901–1902, tested her in Arctic sealing, then sailed from Christiania (Oslo) in June 1903 with only six other men aboard. The route took them across the Labrador Sea and Baffin Bay, then west through Lancaster Sound and along the routes earlier probed by Franklin and others.

By late 1903 Gjøa was frozen into a small natural harbor on the south side of King William Island, where the expedition would remain for two full winters in what is now Gjoa Haven, Nunavut. Here they met and lived alongside Netsilik Inuit families, who effectively kept the expedition alive and transformed Amundsen’s understanding of Arctic travel. Rather than relying on heavy European woolens and man‑hauling, Amundsen adopted Inuit practices: wearing animal-skin clothing that stayed warm even when damp, building snow houses when needed, and using dog teams for transport. During these winters, Amundsen also sledged out to determine the then‑current position of the North Magnetic Pole, work that took extensive field travel and further deepened his dependence on Inuit guidance, food, and techniques.[youtube]

The written record does not single out one specific Inuit man who “cared for him for two years” in the way later heroic narratives sometimes do; instead, Amundsen repeatedly emphasizes how an entire community taught and supported the Norwegians. Individual Netsilik hunters and families hosted, fed, and guided the Gjøa party, but sources treat this as a collective relationship rather than a single named patron.

In 1906 Gjøa finally rounded into the Bering Strait and on to Nome, Alaska, where Amundsen and his crew arrived to a jubilant reception after three years in the ice. From Nome, Amundsen took the news of his success to the wider world; he traveled on from Alaska by ship and then by more conventional means, while Gjøa herself would ultimately be brought south to San Francisco and later returned to Norway as a museum ship.

After reaching Nome in 1906, Amundsen’s long “trek” was less a single heroic dog-sled dash than a series of onward journeys from the edge of the Arctic into the transport networks of the Pacific. His mastery of dog‑sled techniques, learned from the Inuit during the Gjøa winters, shaped not only his local movements around Nome and other Alaskan and Yukon settlements but also his planning for later expeditions, most famously his successful South Pole journey where dog sleds and Inuit-style clothing were central. Contemporary summaries focus on the symbolic climax at Nome—the moment the tiny Norwegian fishing sloop emerged from the Arctic with proof that the fabled passage could be navigated—rather than on a single, dramatic dog-sled relay out of Nome itself.

The Northwest Passage quest was primarily a British obsession in the 19th century, with Norwegian and other explorers entering the story later; Dutch involvement in Northwest Passage searching had largely faded well before Amundsen’s time. After Amundsen’s successful 1903–1906 transit, there was no significant continuation of Northwest Passage attempts by Dutch national expeditions, in part because the commercial and strategic rationale for further, costly voyages in the same region remained weak and the age of steam and later air travel was already beginning to shift Arctic priorities. For Norway, Amundsen’s success effectively closed the chapter on the “discovery” of the passage itself, and Norwegian polar efforts shifted to other goals—the South Pole, trans‑Arctic flights, and the Northeast Passage—rather than repeatedly re‑sailing the Northwest Passage simply to prove it could be done again.

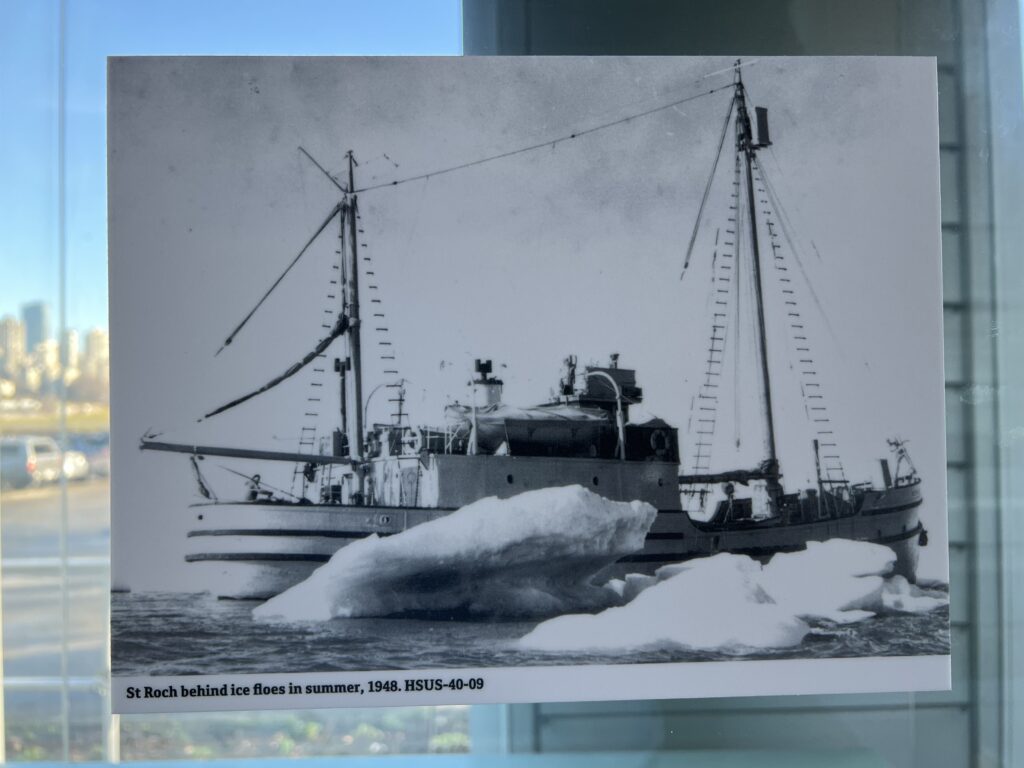

ST. ROCH made her last operational voyage in the summer of 1951. That winter, the RCMP laid up the schooner alongside MacBrien Pier No. 1 at the Halifax Dockyard. Meanwhile, back in Vancouver, a movement to return ST. ROCH to its home port began. In the summer of 1954 the City of Vancouver purchased ST. ROCH from the RCMP. Shortly thereafter Henry Larsen sailed the schooner through the Panama Canal to Vancouver. ST. ROCH arrived on October 12, 1954.

In 1958, the City of Vancouver removed the 1944 deckhouse and restored ST. ROCH to its 1928 appearance. Later that year, workers pulled ST. ROCH ashore on a cradle, where she rests today inside a concrete drydock. In 1962 the federal government recognized the ship’s national significance and designated her a National Historic Site. Together with the City of Vancouver, the federal government entered into an agreement to restore and interpret the vessel. In 1966, the A-frame that covers the ship today was built to protect her from the weather. In 1971, she was completely restored to her 1944 appearance by Parks Canada who then operated the ship as a separate part of the Vancouver Maritime Museum complex for the next 24 years.

In 1995, Parks Canada closed ST. ROCH National Historic Site. Responsibility for the ship passed to the Vancouver Maritime Museum. The long term needs of the ship include a new shelter, restoration of the dry-rotted hull, and an endowment for ongoing preservation. In 1997, the Vancouver Maritime Museum and the RCMP launched a preservation campaign which continues to this day. A dramatic re-enactment of St. ROCH’s voyages in 2000 reached an audience of millions and attracted support, but the task is not yet over. We encourage you to supperu irout efforts to preserve this important and unique piece of Canadian history.

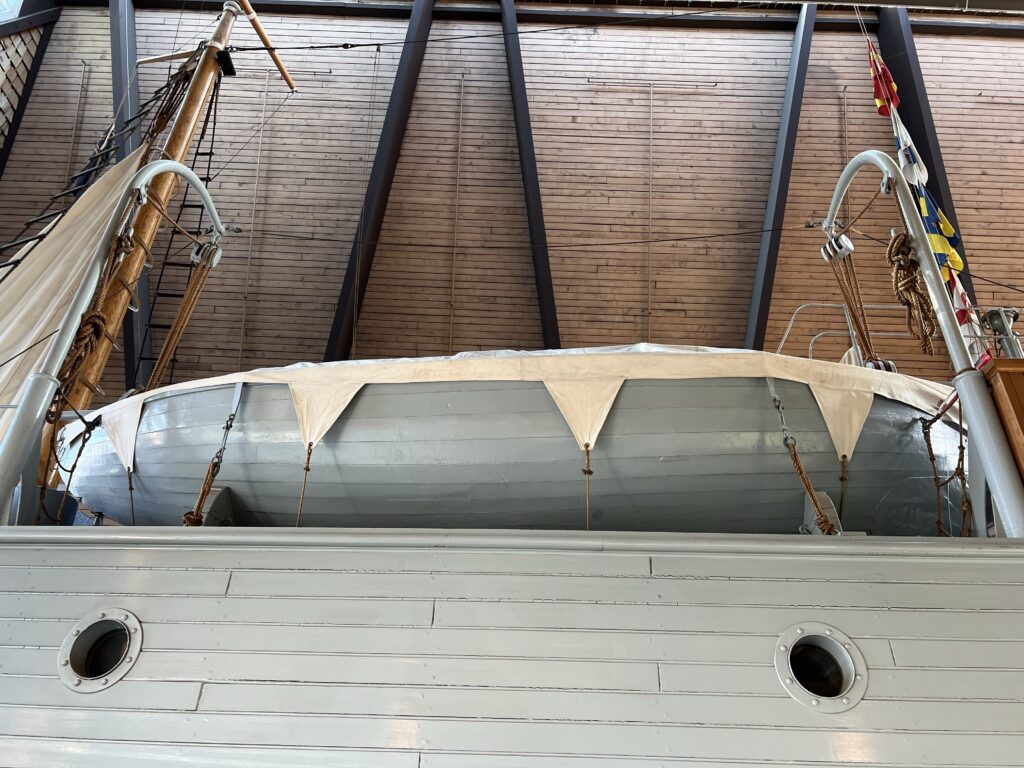

Hull structure and materials

- The hull was built of very thick Douglas fir planking, a strong but resilient softwood that could flex slightly under load.[5][6][1]

- Outside, the fir was sheathed with extremely hard Australian “ironbark” (eucalyptus), giving a sacrificial, abrasion‑resistant skin against ice and grounded floes.[6][1][5]

- Inside, the hull was reinforced with unusually heavy frames and beams so the structure could tolerate long periods under ice pressure without catastrophic failure.[1][5][6]

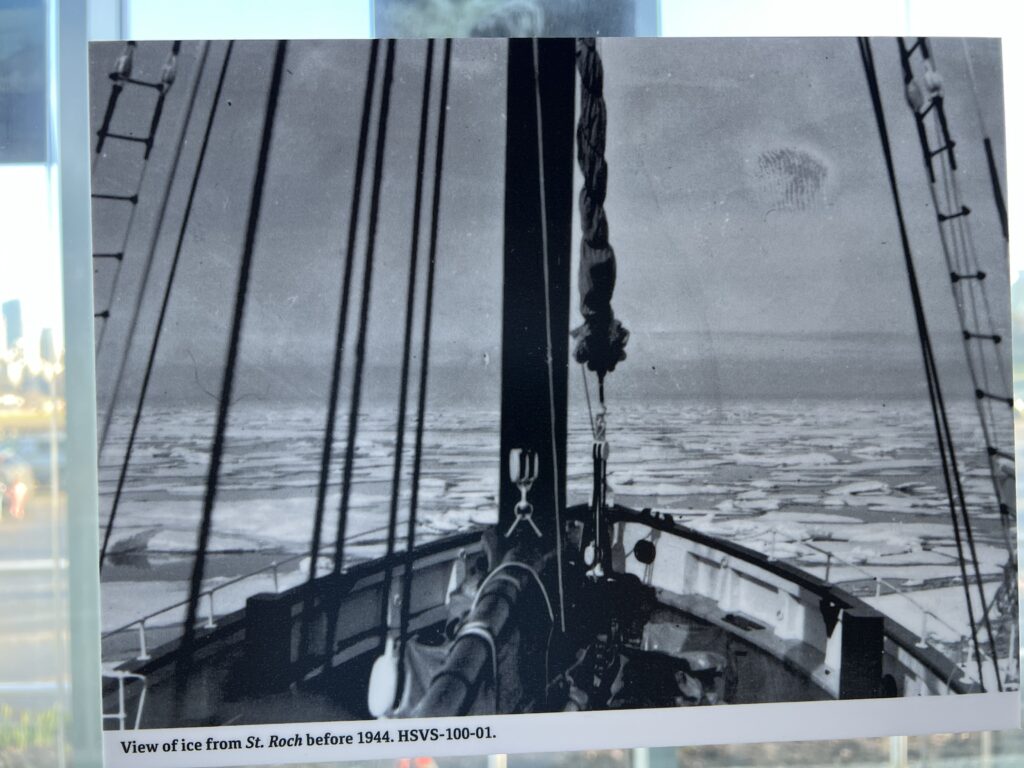

Hull form and ice behavior

- St. Roch had a notably rounded midship section and bottom, with little deadrise, so that when lateral ice pressure increased she tended to be squeezed upward and ride onto the ice rather than be pinched and crushed.[3][6][1]

- This same rounded form made her an uncomfortable, “ugly duckling” seaboat—rolling heavily in open water—but it was ideal for repeated besetment in pack ice.[1]

The bow was additionally protected with steel plating to cope with repeated contact, ramming, and grinding through loose pack and brash ice.[3][6]

Size, scantlings, and propulsion

- At about 90–104 feet in length, with a beam around 24–25 feet and a draft about 10–11 feet (depending on configuration), she was small enough to thread narrow, poorly charted channels but stoutly built (around 190–320 tons) for her size.[5][3][1]

- She was an auxiliary schooner: two masts with three sails plus a 6‑cylinder diesel (roughly 150 hp as built, later replaced by a ~300 hp engine in 1944), giving both redundancy and fine speed control in ice and shoal waters.[4][5][1]

- Wooden construction with treenail fastening reduced catastrophic cracking compared with more brittle all‑steel structures under cyclic ice loading.[5][1]

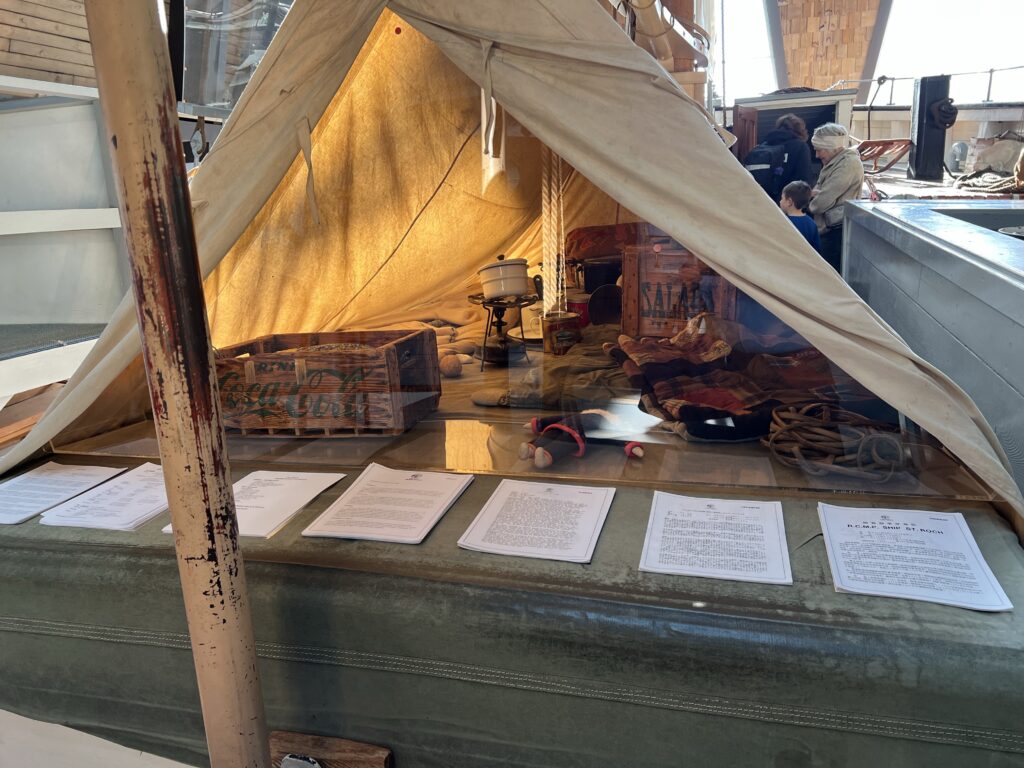

Arctic operational fit‑out

- The deckhouse and superstructure were compact and later enlarged in refit, but remained low and centralized, limiting topweight and exposed surface to wind and ice.[1][5]

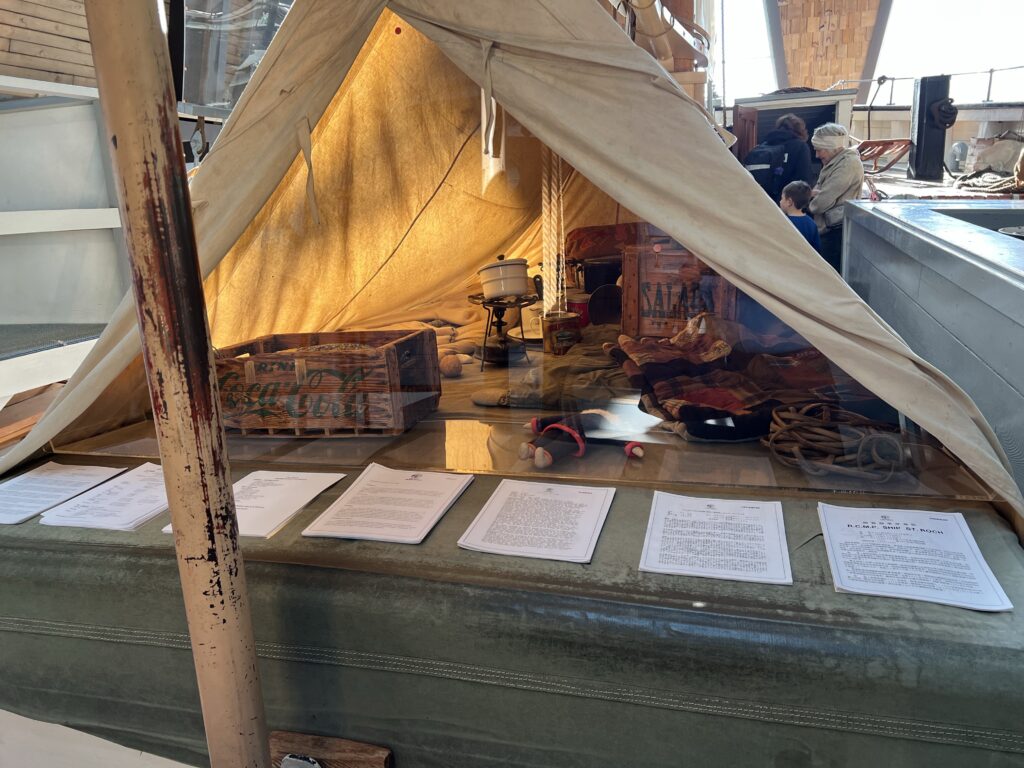

- Internal subdivision, stores spaces, and heating were organized for extended wintering—St. Roch endured multiple winters frozen in, up to roughly ten months at a time—so the ship could safely function as a stationary ice camp when needed.[8][4][5]

- As a patrol and supply vessel rather than a pure research ship, she carried ample cargo and fuel for long unsupported operations, which combined with her hull and rig made her an effective mobile base in the western Arctic.[4][5][1]

Taken together—rounded, heavily built wooden hull; ironbark sheathing and steel‑plated bow; modest size with auxiliary sail and diesel power; and winter‑capable internal arrangements—these features explain how St. Roch could survive repeated besetment, break free from heavy pressure, and ultimately complete multiple historic Northwest Passage voyages and a circumnavigation of North America.[6][4][5][1]

Inuit‑led reinterpretation of St. Roch and its Arctic voyages, foregrounding Indigenous perspectives in the revitalized exhibit announced for winter 2026/27.Sources

[1] St Roch, arctic – Naval Marine Archive

[2] St. Roch National Historic Site of Canada

[3] RCMP St. Roch – Artic Explorer – Historic Ship Of The Week – gCaptain

[4] General Info – St. Roch Research Guide

[5] Our Northern Heritage – the St Roch

[6] St. Roch (ship) – Wikipedia

[7] The Saint Roch, which is built in North Vancouver in 1928 for the …

[8] St. Roch Revitalization – Vancouver Maritime Museum

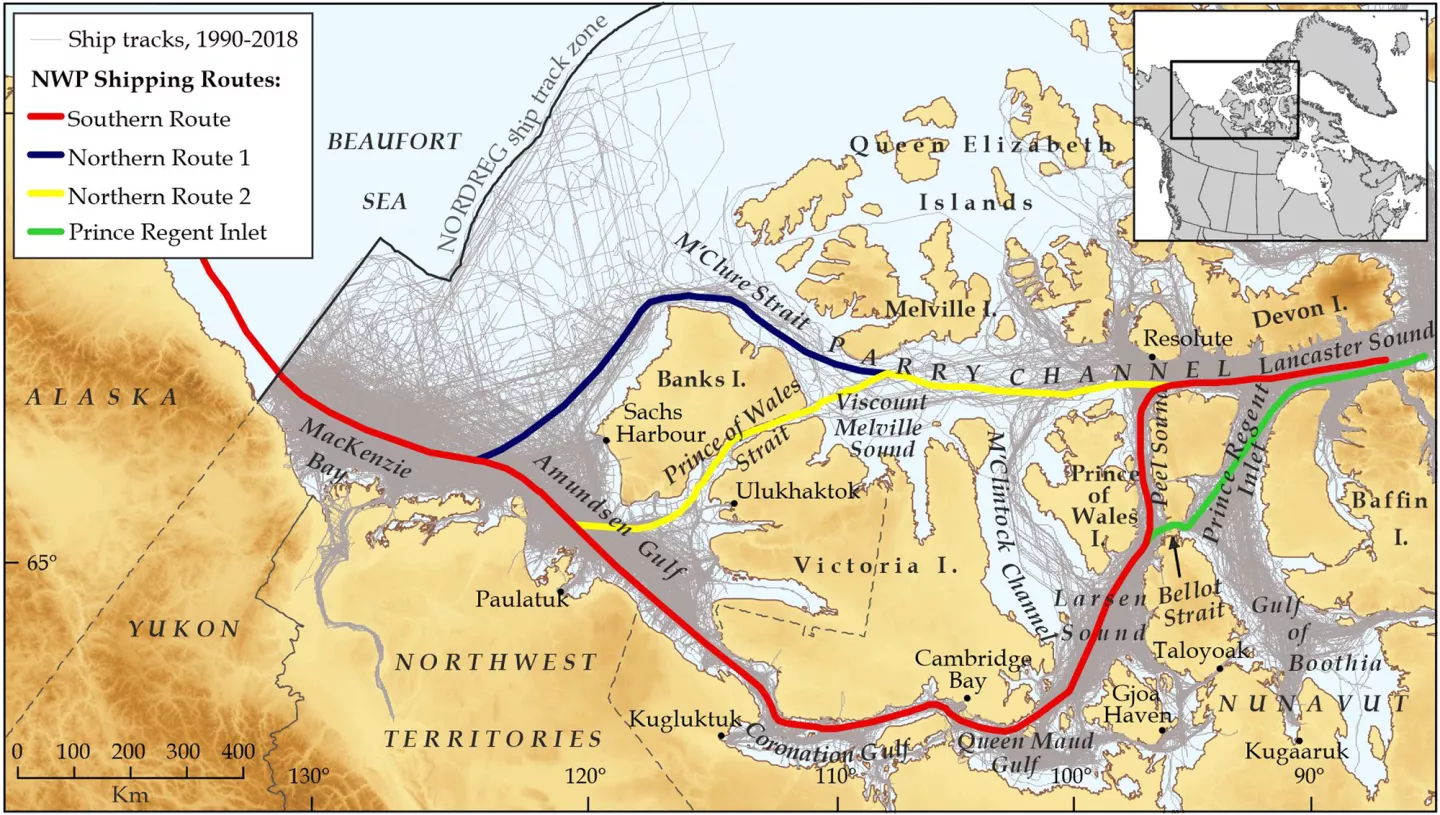

[9] Occasional Paper 124: Arctic Sea Routes: From Dream to Reality

Gallery

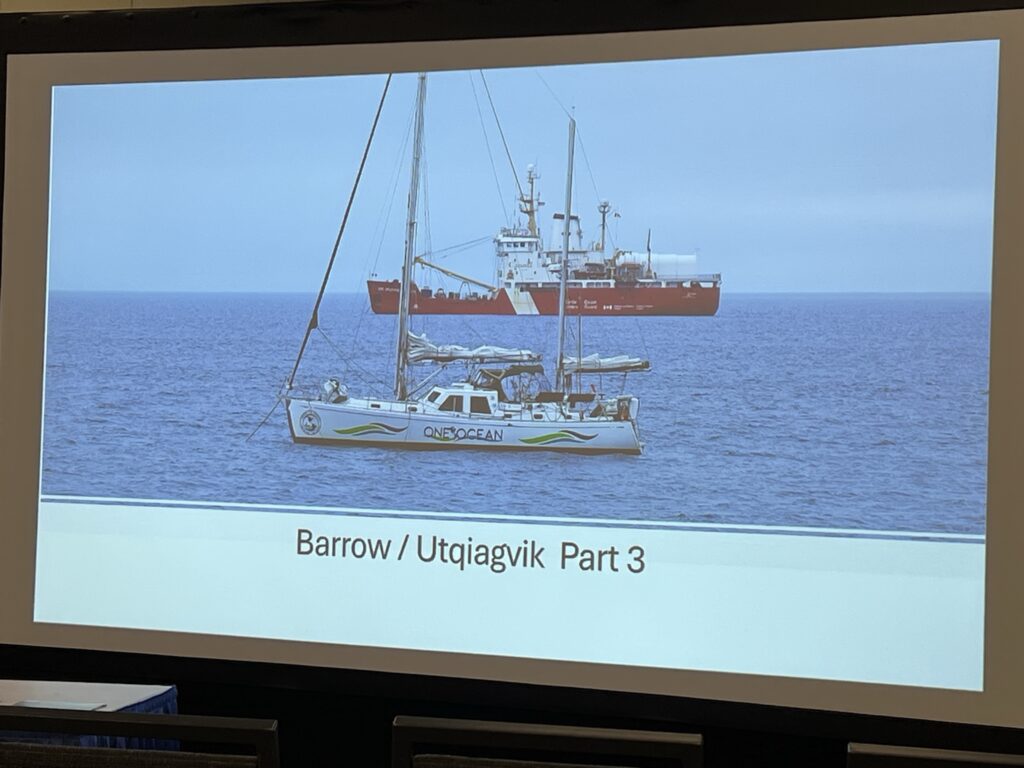

One Ocean

Public information on One Ocean’s 2025 Northwest Passage transit is still limited, so we can outline why they stopped at places like Barrow, McKinley Bay, Herschel Island, Tuktoyaktuk, and Pond Inlet, but not give a full, time‑stamped log for “each anchorage and stop,” nor a precise count of private 2025 transits and failures.48north+2

One Ocean’s key Arctic stops (function and context)

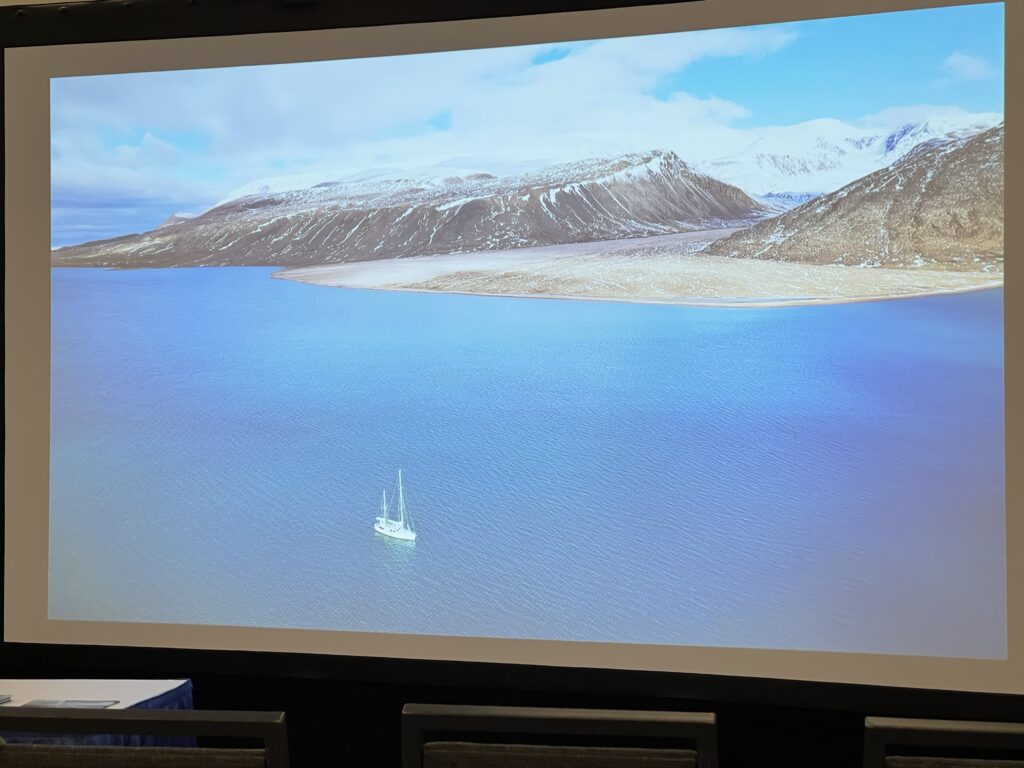

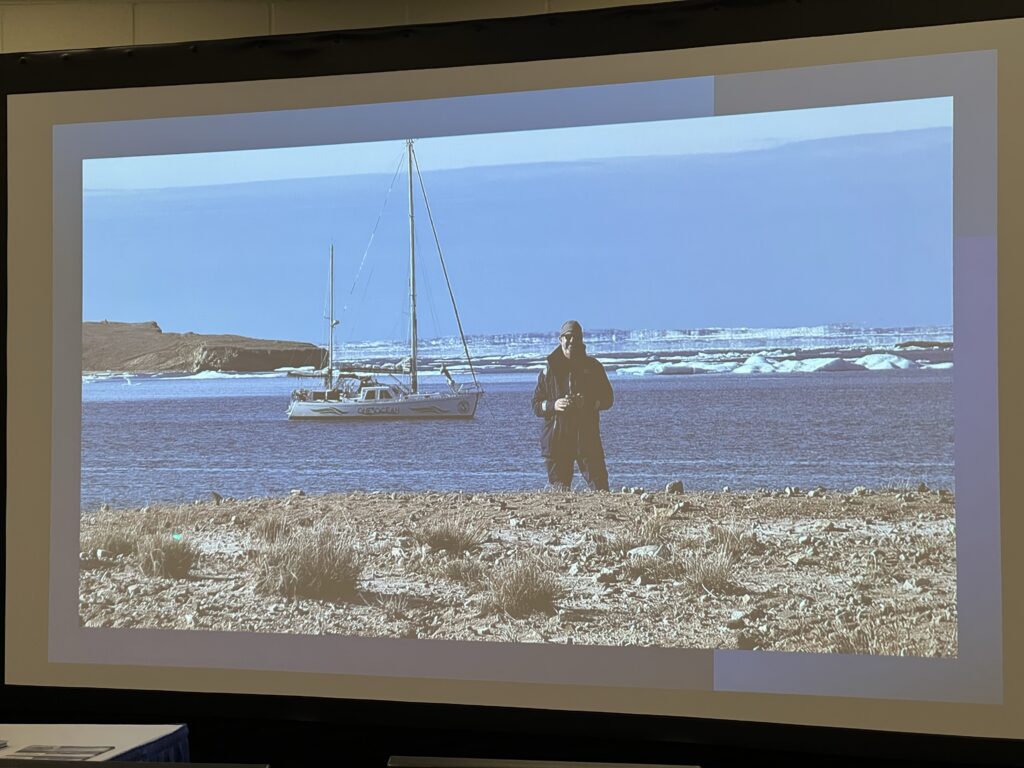

One Ocean is a fiberglass cruising sailboat making a research‑focused circumnavigation of the Americas, with the Northwest Passage leg emphasizing safe ice navigation and kelp/ocean‑health work.ysi+1

One Ocean was not originally designed by Bob Perry as an Arctic‑specific vessel. It is a custom 48‑foot Bob Perry ketch, but its Arctic‑capable features come from a modern refit, not from its original design brief. That refit was done by the Skagit Valley College Marine Technology Center for a long educational and research voyage.

Coopers Island, Alaska

George Divoky has been studying guillemot birds on Cooper Island in Alaska for the last 20 years.

He first discovered a colony of black guillemots there in 1970 and has returned annually to monitor their population and behavior.

Cooper Island is located in the Northwest Passage, and George’s research has been significant in understanding the impact of climate change on these seabirds.

Purpose

Crew were familiar with the Gillamont studies and hoped to meet George.

What was accomplished

Because there are only a few remaining pairs. George chose not to study while One Ocean could visit. The visit was possible because of the need to wait for the ice to break up. In other words this visit was part of the necessity to wait.

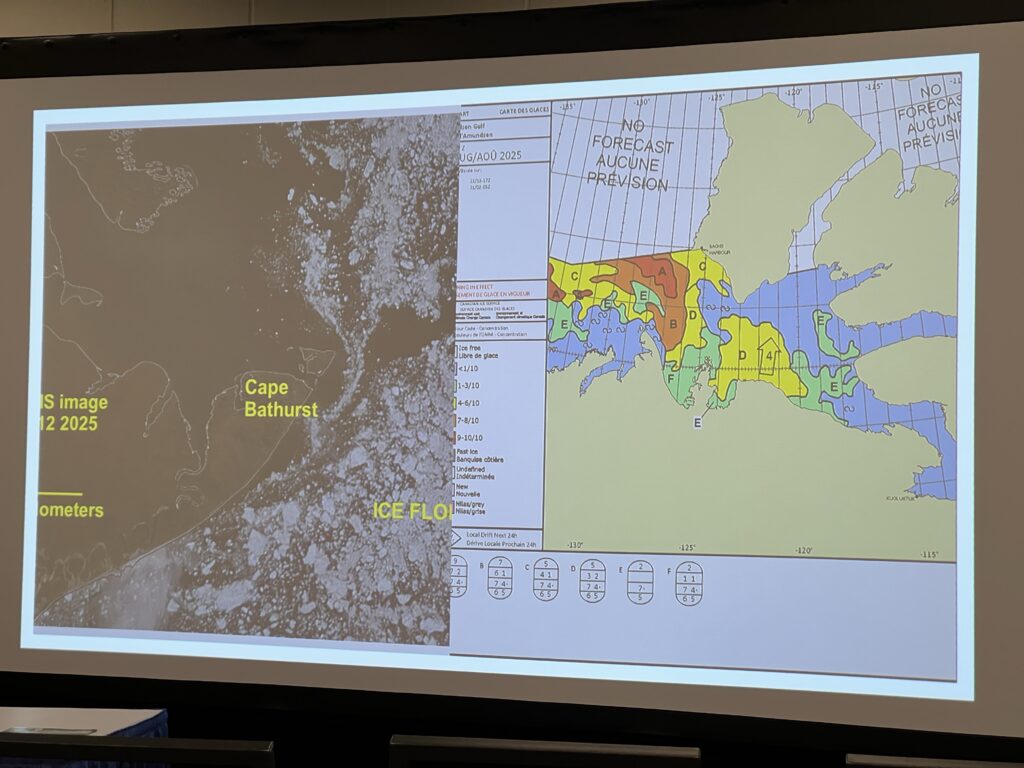

Cape Bathurst

Cape Bathurst (Inuit: Awaq)[1] is a cape and a peninsula located on the northern coast of the Northwest Territories in Canada. Cape Bathurst is the northernmost point of mainland Northwest Territories and one of the few peninsulas in mainland North America protruding above the 70th parallel north.

Purpose

What was accomplished

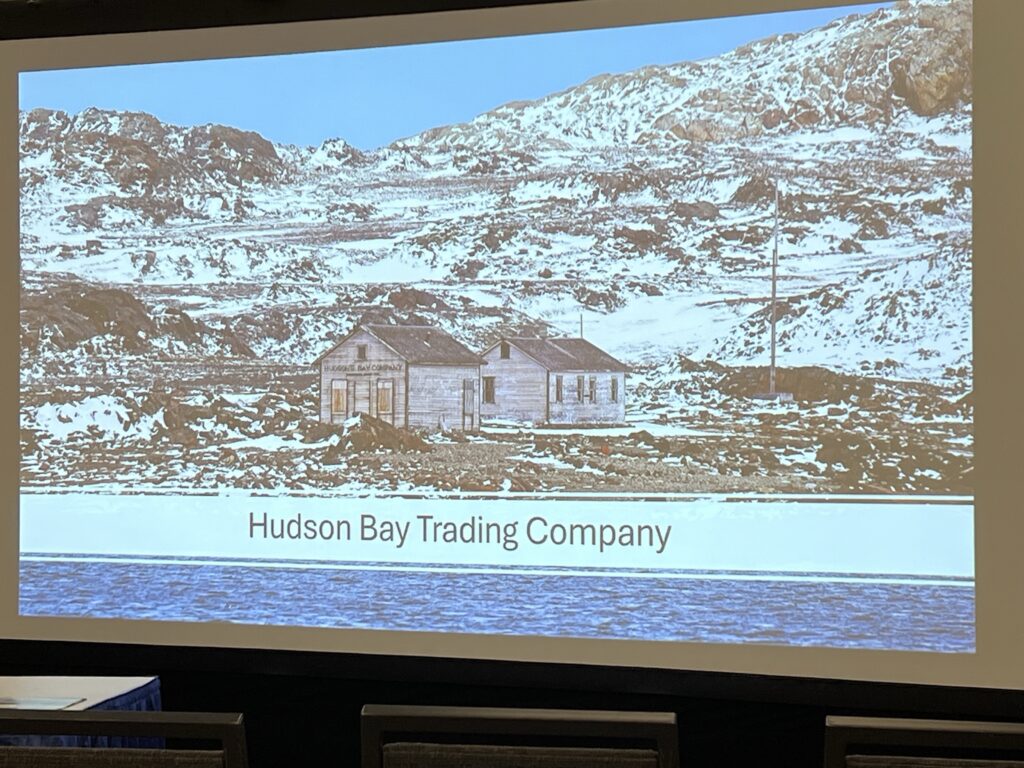

Cape Bathurst features as a key location in Jules Verne‘s novel The Fur Country. In this novel, Cape Bathurst is not a fixed geographical feature but is instead a large iceberg anchored to the continent. A Hudson’s Bay Company expedition is ordered to establish a fort above the 70th parallel north to support fur trapping. The expedition leaders are misled by the appearances of Cape Bathurst into thinking it is a favorable place for settlement. For all intents the cape appears to be very suitable since it has fresh water and is well wooded, with rich soil, vegetation, and abundant wildlife. After building Fort Good Hope they prepare to winter over. During the winter, a volcanic eruption occurs nearby, and unknown to the settlers, the link to the continent is broken and the iceberg “Cape Bathurst” floats into the Arctic Ocean, carrying away the novel’s protagonists.

Wikipedia

Barrow (Utqiaġvik), Alaska

- Purpose: Western staging point at the edge of the Beaufort Sea before entering the ice‑affected section toward the Amundsen Gulf, used to wait on ice charts, weather windows, and prepare the crew for short‑watch, high‑concentration ice piloting.[youtube][48north]

- What was accomplished: From the available narrative, the key achievement in this sector was transiting “a severe plug between the Beaufort Sea and Amundsen Gulf that had blocked ships from transiting the Northwest Passage all summer,” threading through 3–5/10 and then heavier ice without hull damage.

- Barrow served One Ocean mainly as the start of this push.[48north]

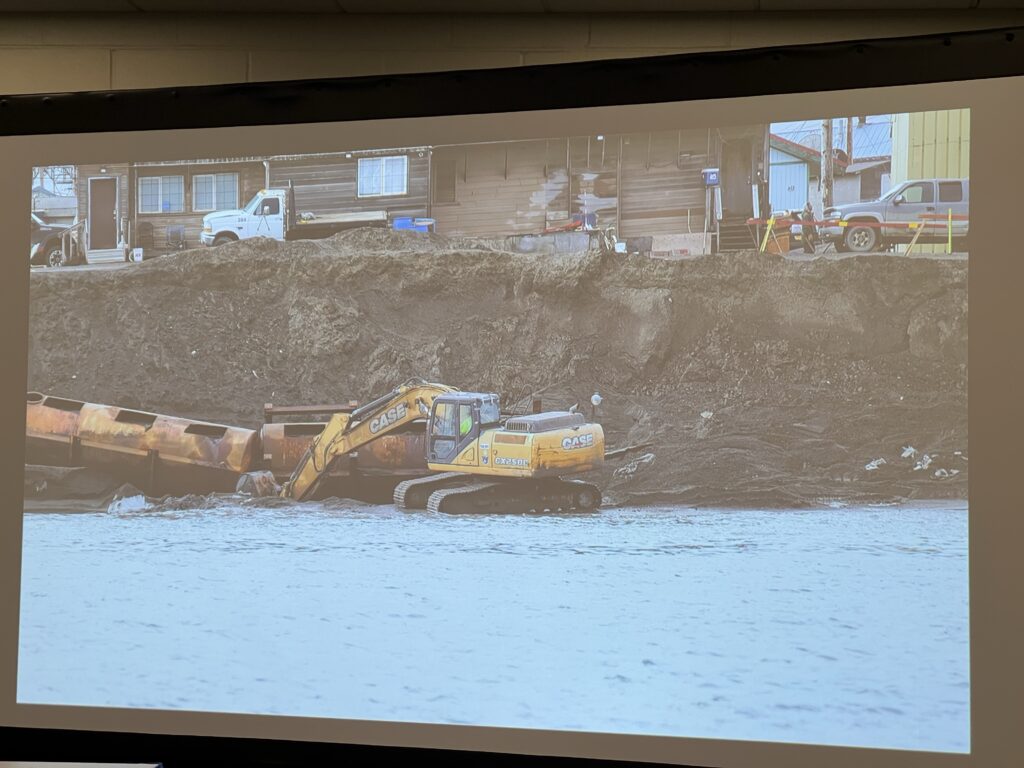

The visit also documented the seawall project that was started in 2025.

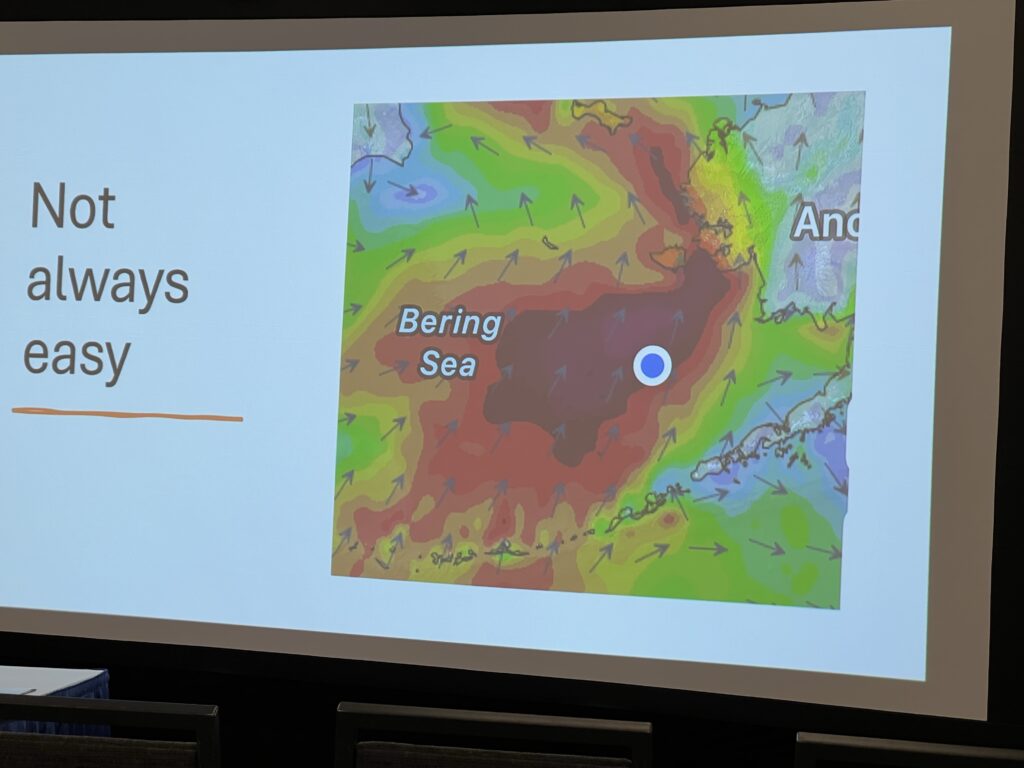

The Bering Strait is captivating due to its unique blend of natural and cultural significance. It’s a narrow passage that separates two continents, Asia and North America, with a mere 55 miles between them.

This geological marvel is also a vital migratory route for numerous species, including whales and seabirds. Moreover, it holds historical importance as a bridge for early human migrations. These are the traditional homelands of Inupiaq and Yupik peoples. The Bering Strait is also a crossroads where geology, history, and culture converge, making it a fascinating destination.

2. International Date Line

Conditions permitting, we may be able to briefly sail past the international date line where for a few moments you will have ‘tomorrow’ on one side and ‘today’ on the other. But don’t worry about changing your calendar as our crossing will be brief and ceremonial!

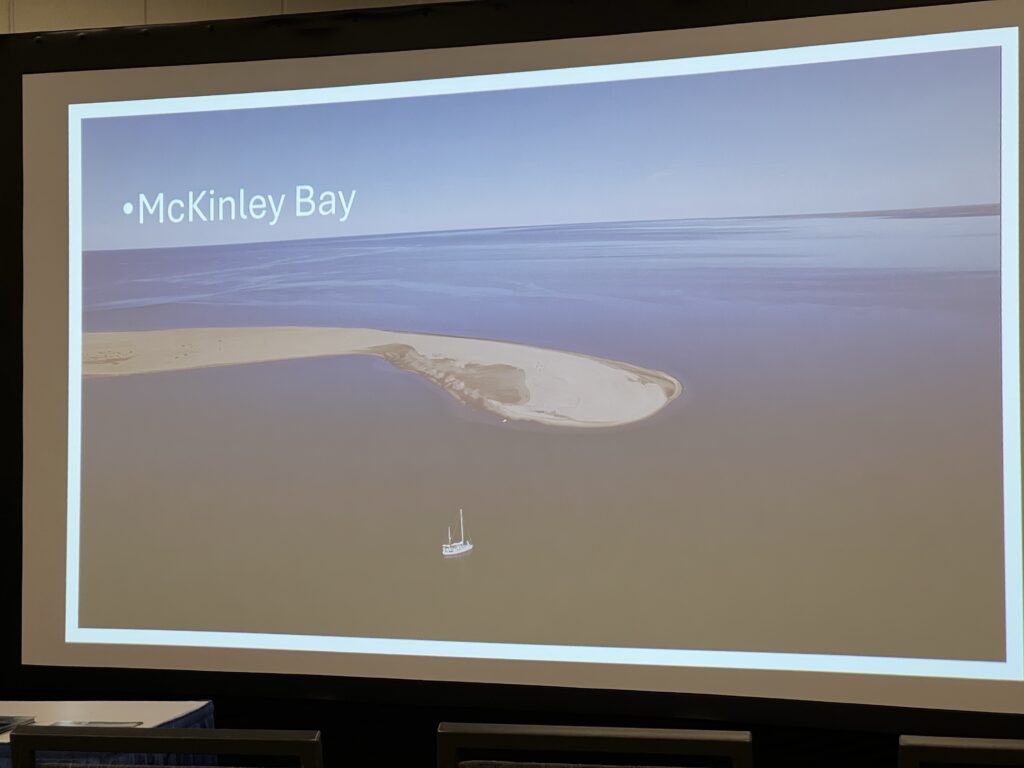

McKinley Bay (Beaufort Sea, NWT)

- Purpose: A relatively sheltered indentation on the mainland coast, often used as a weather and ice‑waiting anchorage on the way east from Alaska; it offers a place to step out of pack‐ice drift and strong winds, check satellite ice imagery, and reset watches.[waves-vagues.dfo-mpo.gc]

- What was accomplished: Public write‑ups on One Ocean don’t detail a specific incident at McKinley Bay, but in typical yacht routings it functions as a tactical stop: fuel checks (if supported by a tender or pre‑position), rig inspections after the first ice, and crew rest before the next stretch of ice and shoals.

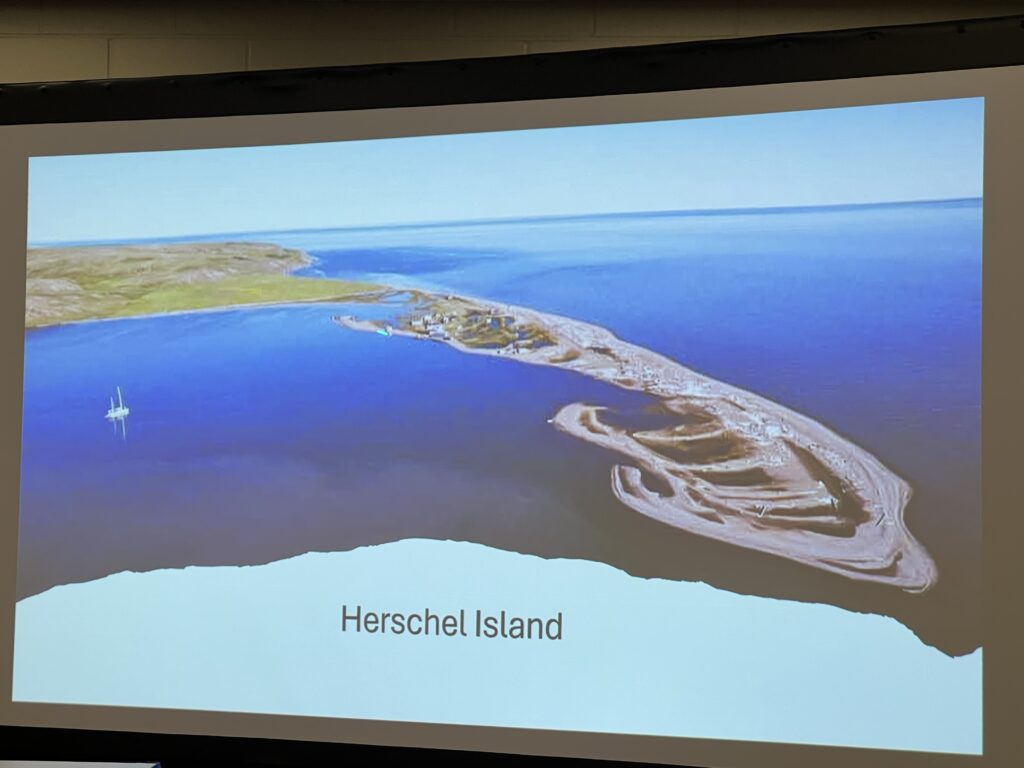

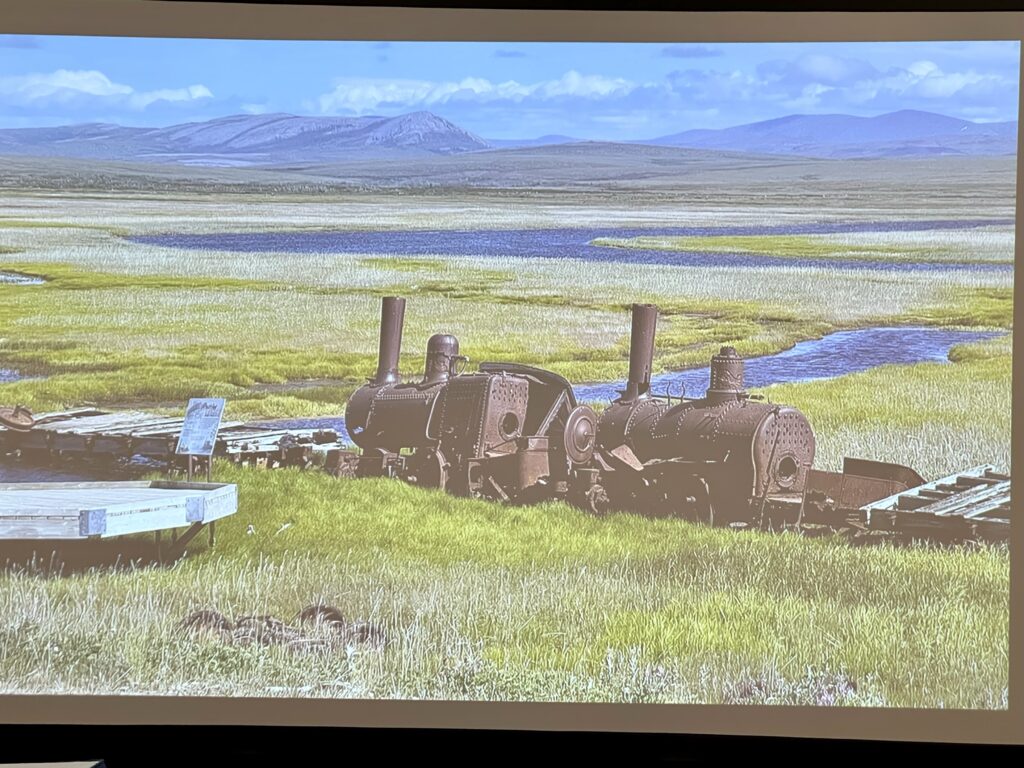

Herschel Island (Qikiqtaruk), Yukon

Purpose: Historic outpost and former whaling hub just off the Yukon coast, now a territorial park; for transiting yachts it’s a landfall and cultural/natural history stop after the initial Beaufort segment.whoi+1

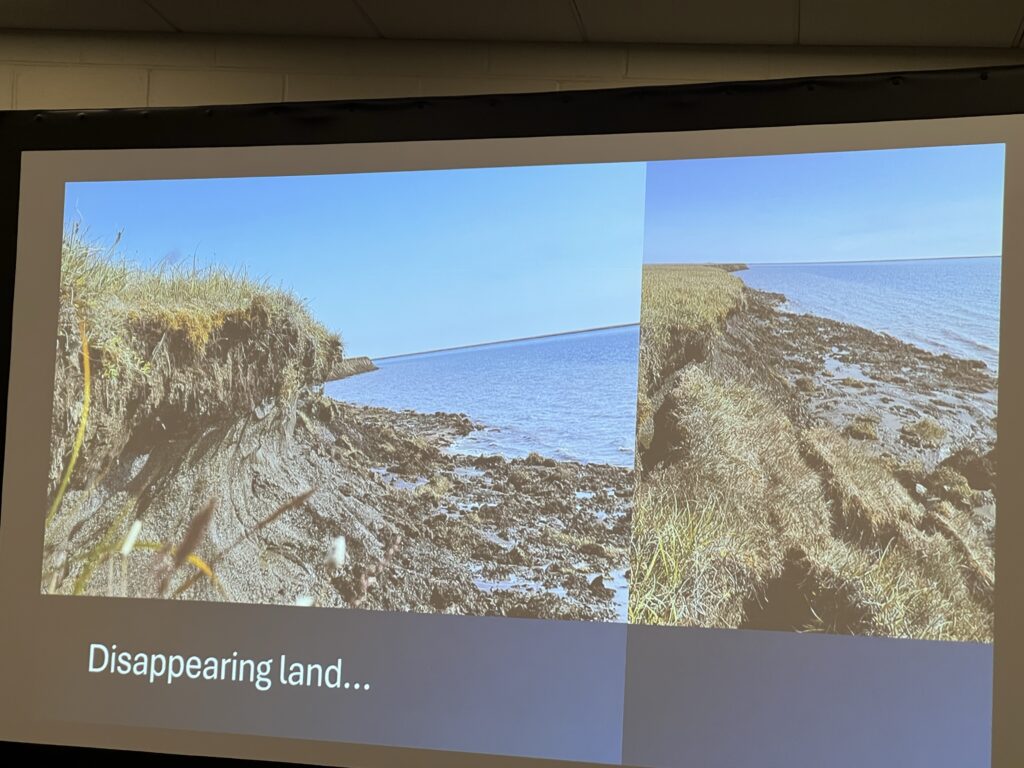

What was accomplished: Crews normally go ashore (conditions permitting) to see the old RCMP post and whaling buildings, walk the permafrost bluffs, and check in with Parks staff or researchers if present; this also offers a chance to recalibrate local ice/shorefast conditions based on resident knowledge. There is no detailed, time‑stamped One Ocean report publicly tying a particular date to Herschel.

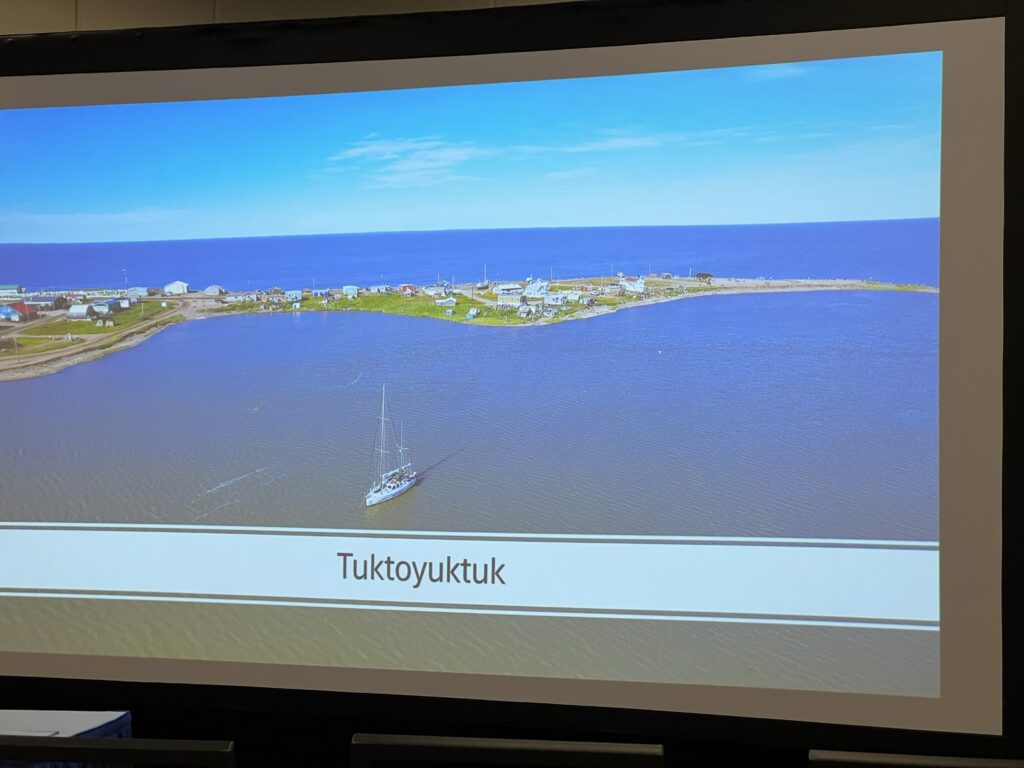

Tuktoyaktuk, NWT

- Purpose: First road‑linked Arctic Ocean community on the Canadian side, used as a logistics and community stop—for fuel top‑up (if arranged), limited provisions, local weather/ice intelligence, and crew morale (showers, meals ashore, seeing the Arctic Ocean sign, etc.).spectacularnwt+1

- What was accomplished: A visit typically includes seeing the Pingo Canadian Landmark from town or by tour, visiting the Inuvialuit sod house and permafrost “deep freeze” cellars, and engaging with local guides; it’s also a natural social waypoint for yachts and small ships in the Beaufort. One Ocean’s own public content confirms a Tuktoyaktuk stop but does not publish a detailed log entry with exact date/time.tripadvisor+2

Land of the Midnight Sun Music Festival

Tuktoyaktuk’s top attractions center on its unique Arctic geology, Inuvialuit heritage, and position as Canada’s northernmost highway-accessible community.spectacularnwt+2

Natural landmarks

- Pingo Canadian Landmark: The standout draw is this protected site 55 km east, home to eight pingos (ice-cored hills), including Ibyuk Pingo, Canada’s largest at 49 m high and 300 m wide; it’s the world’s highest known concentration of these permafrost mounds, with interpretive signs explaining their formation.tripadvisor+2

- Arctic Ocean shore: A simple sign marks the spot to “dip your toe” in Canada’s Arctic waters, often with locals netting fish or spotting beluga whales in season.wanderlog+1

Cultural and historical sites

- Traditional sod house: A reconstructed Inuvialuit dwelling shows pre-contact architecture—driftwood frame, sod-covered, with an entry tunnel to trap cold air—used for living, storytelling, and winter warmth via oil lamps.spectacularnwt+1

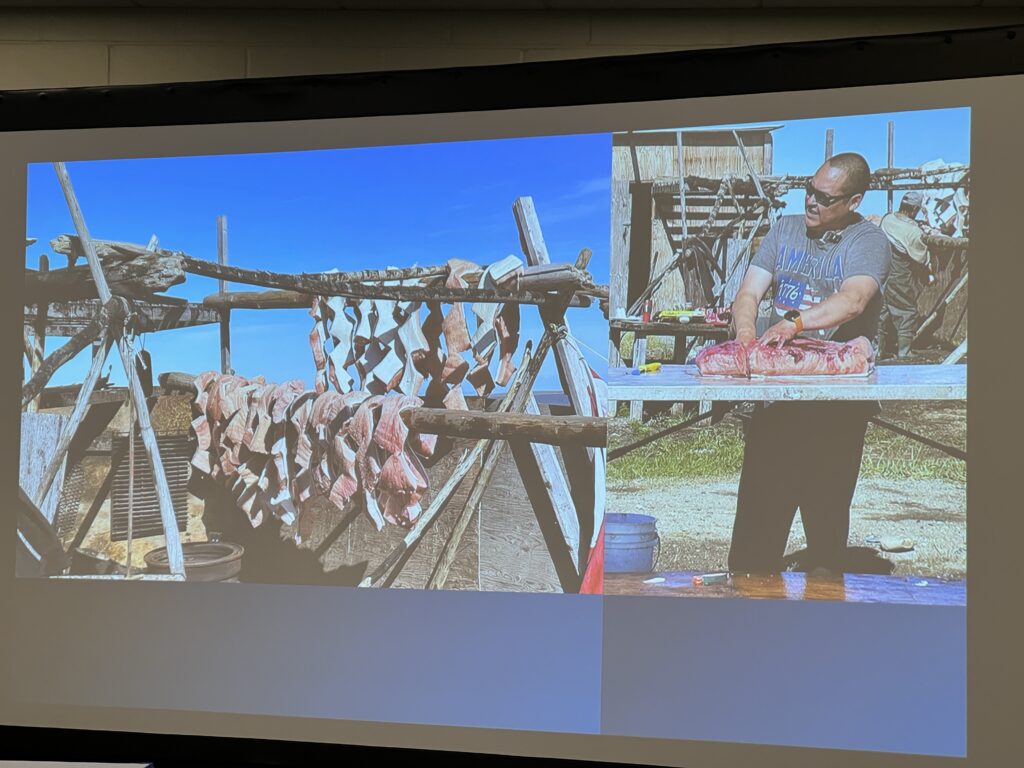

- Permafrost “Deep Freeze” caves: Community-carved cellars in the frozen ground store hunted food like whale and seal; tours from the visitor center reveal these practical permafrost pantries.tripadvisor+1

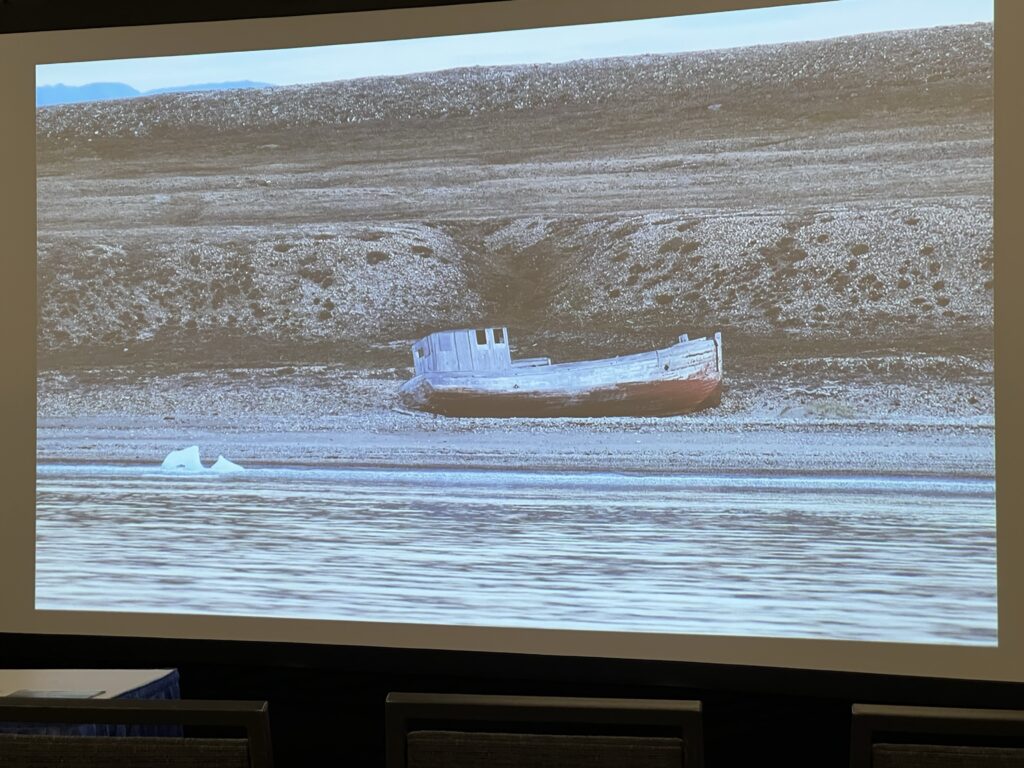

- Our Lady of Lourdes ship: A rusting schooner from early 20th-century trade, now a landmark with pleas for preservation.[tripadvisor]

Community highlights

- Tuktoyaktuk Visitor Information Centre: Start here for maps, tours to pingos/caves, beluga jamboree info (spring festival), and the community’s four-season events like the Midnight Sun Music Fest.wanderlog+1

- DEW Line site: Cold War radar relics from the Distant Early Warning network, offering a glimpse into Arctic defense history.[spectacularnwt]

These spots make Tuk a memorable stop for geology buffs, cultural explorers, and road-trippers ending the Inuvik–Tuktoyaktuk Highway.spectacularnwt+2

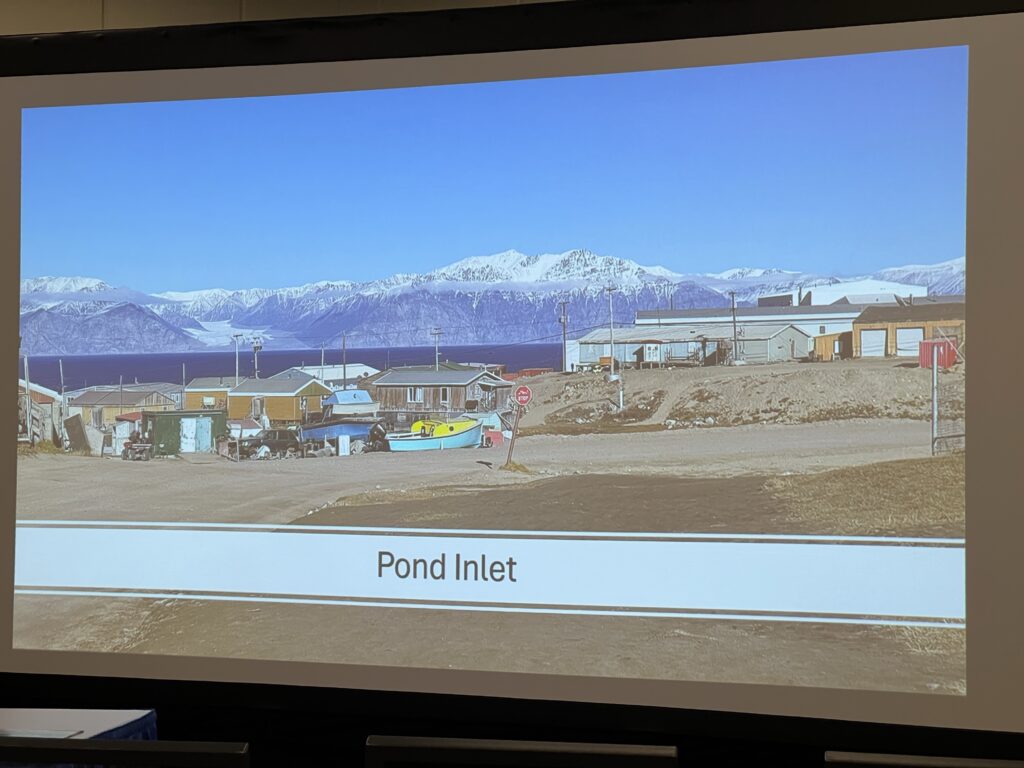

Pond Inlet, Nunavut

- Purpose: Major Inuit community on northern Baffin Island, commonly used as an eastern gateway or exit port for Northwest Passage voyages: customs/immigration for foreign yachts, fuel (if arranged), provisions, and as a crew change and staging point for Baffin Bay.arctickingdom+1

- What was accomplished: For a westbound transit, Pond Inlet is often the last major settlement before entering Lancaster Sound; for an eastbound yacht like One Ocean it would be the first substantial community after the central archipelago. Activities typically include formalities, provisioning, and sometimes local guiding or wildlife watching (narwhal, seabirds), but specific dates and tasks for One Ocean have not been published in text form accessible so far.

Dates and noteworthy events

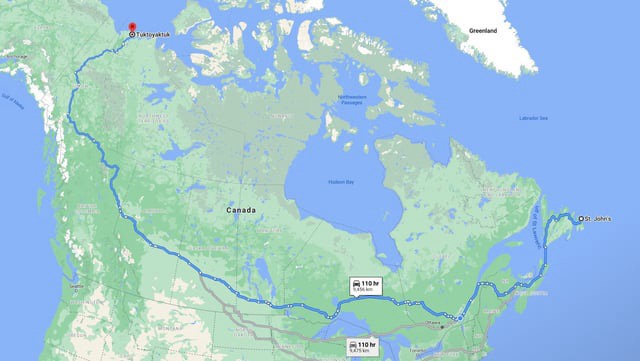

- The clearest public date is that the One Ocean crew “officially complete the Northwest Passage” on 12 September 2025, after 52 days in the Arctic Circle.[instagram]

- The “noteworthy” feat highlighted in media coverage is their successful, hull‑intact crossing of the Beaufort–Amundsen “plug,” which had stopped or deterred other traffic earlier that summer; this is reported in narrative rather than a formal log with coordinates.[48north]

Because no full logbook with timestamps and a stop‑by‑stop breakdown has been released, we cannot reliably provide exact date/time for each anchorage or describe every single accomplishment beyond these broad functions.ysi+1

Vessel sightings by One Ocean

- The 48° North article and project materials describe One Ocean working through areas that had “blocked ships from transiting the Northwest Passage all summer,” but they do not name specific other vessels sighted or give positions of notable close‑quarters encounters.belfercenter+1

- Without AIS data or a detailed log, we cannot state “where One Ocean sighted another vessel” with confidence; those details are simply not in the public written record yet.[48north]

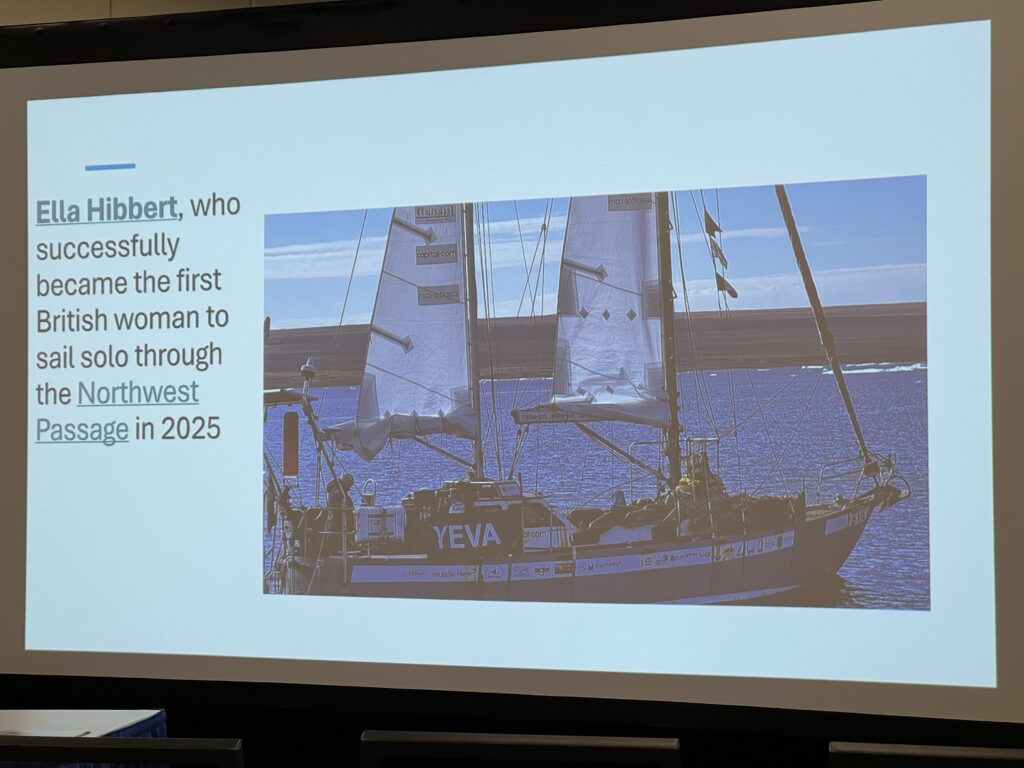

Who is Ella Hibbert?

- Ella Hibbert is a 28‑year‑old British sailor, RYA Yachtmaster Instructor and PADI divemaster who, in 2025, became the first British woman to sail the Northwest Passage solo.yacht+1

- She is attempting a solo circumnavigation of the Arctic Circle in her 38‑foot steel ketch Yeva (built 1978), combining the Northwest Passage and, in a later season, the Northeast Passage.pbo+1

- Her project also has a scientific component: in collaboration with the British Scientific Exploration Society and the International SeaKeepers Society, she is collecting seabed and oceanographic data to contribute to the Seabed 2030 mapping initiative.[yacht]

- In 2025 she completed the Northwest Passage portion, sailing from southern England past Iceland, along Greenland, then through the Passage, but had to pause the overall Arctic circumnavigation due to delays, equipment failures, rough weather, grounding, and Russian authorities warning her about late‑season ice in the Northeast Passage.pbo+1

Private Northwest Passage transits and failed attempts in 2025

- A recent policy summary notes 117 complete Northwest Passage transits between 2020 and 2024, of which 48 were yachts or other private vessels (about 41%).[belfercenter]

- However, no authoritative, consolidated dataset for 2025 transits is yet published in the main open statistics sources; the widely cited transit tables currently extend only through 2024.thenorthwestpassage+1

- Media and expedition reports confirm that at least a handful of private boats, including One Ocean and Ella Hibbert’s Yeva, made successful 2025 transits, but they do not yet aggregate into a verified count like “X private vessels completed in 2025.”yacht+2

- Likewise, while narratives mention that the Beaufort–Amundsen ice “plug” stopped other ships earlier that summer, they do not provide a systematic list of failed private attempts or detailed reasons beyond the usual combination of heavy ice, equipment problems, schedule pressure, and, in Ella Hibbert’s case, late‑season ice risk in the Russian sector leading to a voluntary stop.pbo+2

So at this point you can say with confidence that several high‑profile small‑craft transits occurred in 2025 (One Ocean, Yeva), that heavy ice forced some vessels to turn back or delay, and that solo sailor Hibbert suspended her full Arctic circumnavigation attempt; but you cannot yet quote a precise number of private transits or a complete catalog of failures for the 2025 season from public data.belfercenter+3

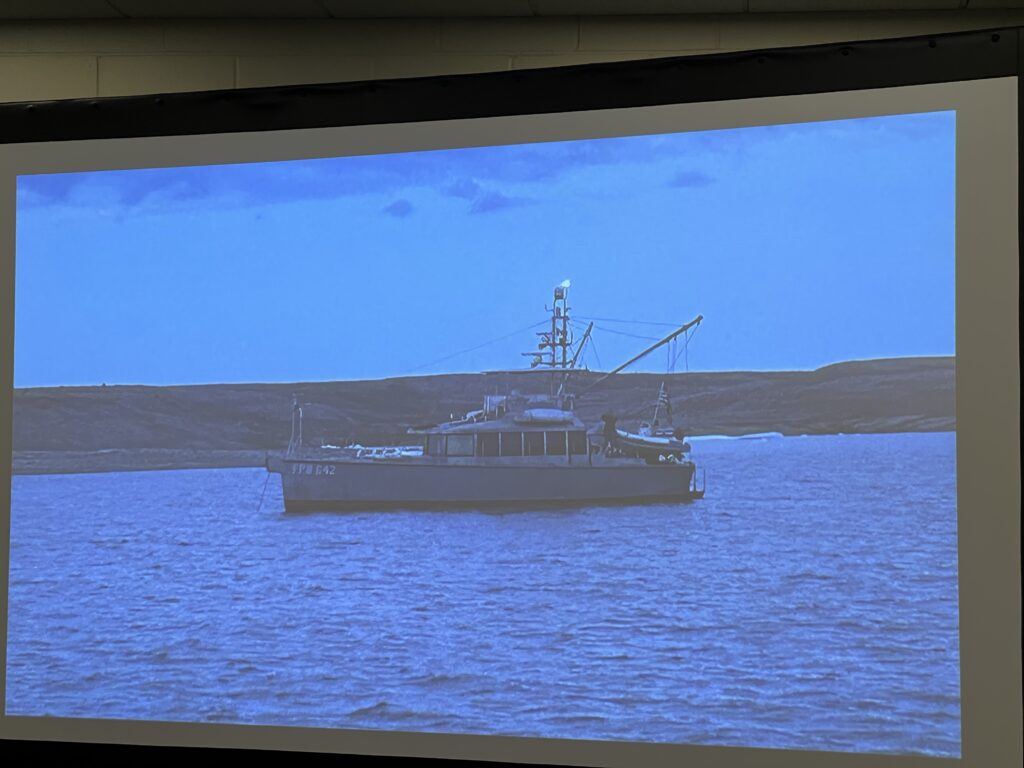

Sarah-Sarah

Sarah-Sarah was built by Circa Marine in New Zealand and is Hull #2 of 11 FPB-64s designed by Steve and Linda Dashew. She completed the Northwest Passage going East to West at about the same time One Ocean completed going West To East.

Driven by a single John Deere 6068 SFM Marine Diesel configured for 236 HP, Sarah Sarah cruises at ten knots and could motor from Virginia to Portugal, and back, without stopping to refuel. At 8.6 knots, she could turn around and head back …and make it.

Purpose build to go absolutely anywhere in the world, FPBs are build for function, safety, redundancy, and efficiency.

“Rig the dinghy!” For a second, I thought I was wrong about him being the right captain for the job as I helped sling the 40-hp setup over the side. When Scott drove the dinghy around to the starboard rail and lashed it in a side tow to the 85,000-pound vessel, I really thought I had picked the wrong guy.

Three minutes later, I was at the helm as we made an easy 5 knots. We were fine. Scott put his hand on my shoulder and said with a laugh, “We maintain 9.5 knots using just 75 horsepower from our main engine. It stands to reason that 40 horsepower can get us underway, right?”

Scott wasn’t guessing. His planning job had been vessel operations. He knew his boat, and he had a plan for everything that might go wrong.

Two hours later, we were at anchor in a perfect little bay. We replaced the low-pressure fuel pump the next day. Scott had two spares, of course.

Pg 40 south of Devon Island, engine failure in Soundings February 2026

Sam Devlin, the well‑known Olympia, Washington, plywood‑epoxy designer‑builder, was a crew member on Sarah-Sarah in 2025 and biographical note for Scott, skipper of the motor vessel Sarah‑Sarah, states that he and his father “had a boat built in Olympia, WA by Sam Devlin” and that “2025 was the year for the Northwest Passage. Crew from One Ocean spent time with crew from Sarah-Sarah while at anchor

Also aboard was Sam Devlin of Devlin Designing Boat Build-ers, an expert on marine diesels and vessel propulsion with decades of experience. Sam is also wildly funny. He had five stories for every occasion.

Another Kind of Epic in Soundings February 2026 by Mario Vittone

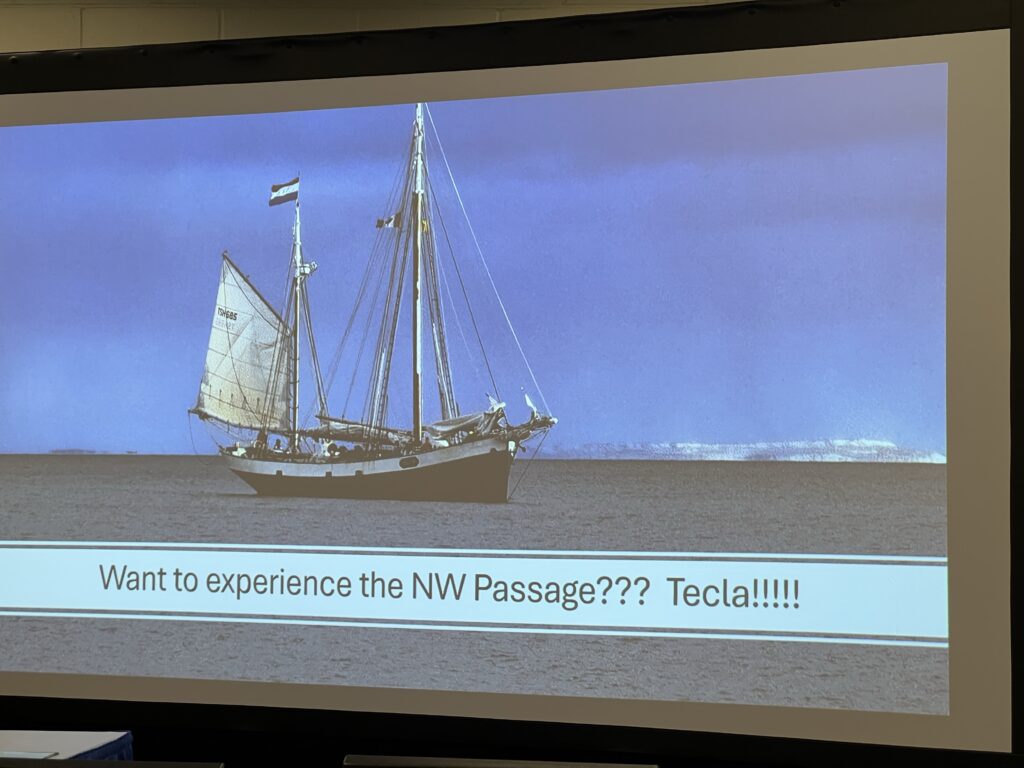

Tecla Tall Ship

Tecla sells its Northwest Passage as a 52‑day, hands‑on tall‑ship expedition from Dutch Harbor (Alaska) to Nuuk (Greenland); you book directly with Tecla or via a partner agency, and the price (~€23,400–€26,000, roughly USD 25–27k) covers your berth, all food, fuel, ice navigation, and guided shore excursions.tecla-sailing+2

Tecla is a Dutch, steel‑hulled, gaff‑rigged former herring drifter (logger) built in 1915 in Vlaardingen for North Sea sail fishing, now converted into a small expedition tall ship for adventure and sail‑training voyages, including the Northwest Passage. She is about 28 m on deck (38 m overall), ketch‑rigged with traditional sails, carries roughly 12–16 guest crew plus 4–5 professional crew, and is owned and run by a single sailing family.

Tecla’s earlier names and how she was named

When launched in 1915 she was not called Tecla at all; she was originally named Graaf van Limburg Stirum, working as a sail‑powered herring drifter out of the Dutch port of Katwijk (fishing number KW143). In 1935 she was sold to Danish owners as a small cargo vessel and renamed Marie/Maria, then around 1960 sold again within Denmark and renamed Tekla when registered in Aalborg.

In the mid‑1980s she was brought back to the Netherlands, rebuilt as a charter/tall ship, and relaunched under the slightly altered form Tecla, which is the name she has carried ever since. None of the operator or history sources explain a specific person or story for the modern name “Tecla”; instead, they emphasize that it is an evolution of the Danish cargo name “Tekla” adopted when she was converted to her current role.

How to book Tecla

- Direct with Tecla:

- Go to Tecla’s official site and open the “North West Passage” voyage page, which lists dates, price (shown as €26,000 with “early bird” €23,400), and itinerary.[tecla-sailing]

- Use their online booking/enquiry form on that page or the site’s contact/booking section to reserve a berth; they confirm availability, send terms and payment schedule, and take a deposit to hold your place.[tecla-sailing]

- Through an adventure agency:

- Agencies like VentureSail Holidays list the same voyage (“North West Passage Sailing Adventure: Alaska to Greenland”) with dates (embark Dutch Harbor 27 July 2025 at 18:00, disembark Nuuk 16 September at 10:00) and price “from £20,275 / €23,400 per person,” with a “View tickets and availability” booking button.[venturesailholidays]

- Booking through them follows normal expedition‑cruise practice: choose date, reserve berth, pay deposit, then complete medical/experience forms.

What you get for the money

Voyage and ship

- 52‑day Northwest Passage attempt: Dutch Harbor → Nome → across the Chukchi/Beaufort Seas → Canadian Arctic (possible stops Taloyoak, Cambridge Bay, Gjoa Haven, Resolute, Beechey Island, Pond Inlet) → finish in Nuuk, Greenland; route and exact stops depend entirely on ice and weather.venturesailholidays+1

- Historic sailing ship: Tecla is a 28 m, family‑run Dutch gaff‑rigged ketch/tall ship carrying up to 12 guests plus 3–4 professional crew, kept traditionally rigged but with modern safety and navigation gear.anotherworldadventures+1

Accommodation and life on board

- Twin en‑suite cabin: Price includes a berth in a 2‑person bunk‑bed cabin with private toilet/shower, bedding and fresh sheets, towels, and weekly laundry.tecla-sailing+1

- All meals: All food on board (or packed lunches for shore days) is included.[tecla-sailing]

- Warm, heated interior: Central heating keeps the saloon and cabins comfortable even when temperatures outside drop below freezing.venturesailholidays+1

What’s included operationally

From Tecla’s Northwest Passage inclusions list (for similar legs):[tecla-sailing]

- Berth in 2‑person en‑suite cabin.

- All meals on board (plus shore‑day lunch packs).

- Bedding, sheets, towels, weekly clothes washing.

- Ice pilotage and fuel.

- Harbour dues/berthing costs.

- Dinghy transfers and excursions.

- Planned shore excursions and permits for Inuit settlements, plus guided walks on land.

- Permanent professional crew of 3–4.

What you do as a guest

- You are treated as “expedition crew”: encouraged (and expected) to help raise and trim sails, stand on deck, take the helm under supervision, and participate in the daily sailing routine.tecla-sailing+1

- You receive presentations and briefings on ice navigation, Tecla’s history, and the history of Northwest Passage explorers, as well as updates from ice charts and weather reports sent to the ship.[tecla-sailing]

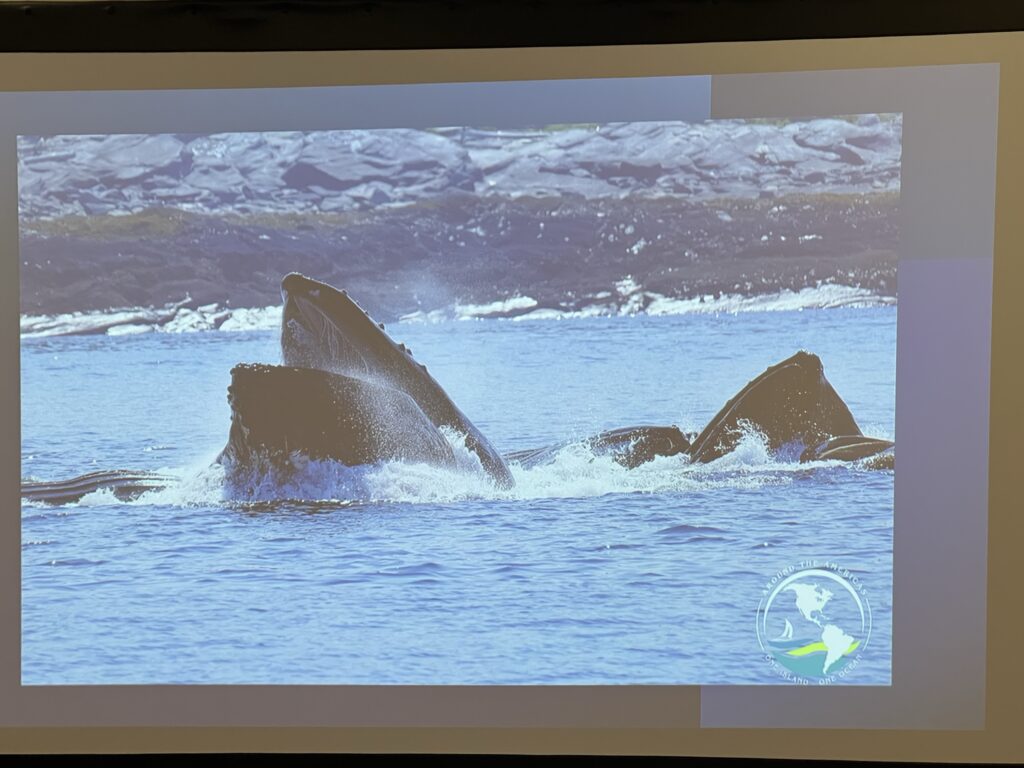

- In off‑watch time you can watch for wildlife (polar bears, whales, seabirds), photograph the landscape, or relax in the heated saloon with books and fellow guests.venturesailholidays+1

In short, that ~USD 27,000 buys you a berth on a small, fully crewed tall ship for about seven and a half weeks, with all meals, fuel, permits, ice navigation, and guided shore time included, plus the chance to actively sail a traditional vessel through the Northwest Passage rather than passively cruise on a larger ship.anotherworldadventures+3

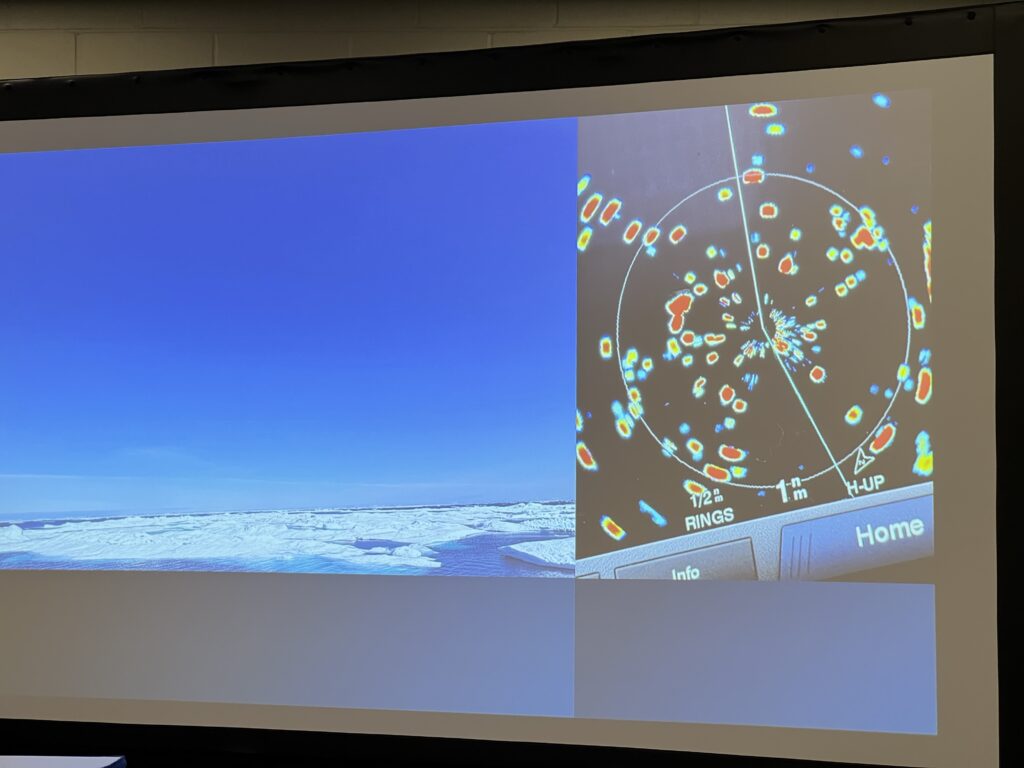

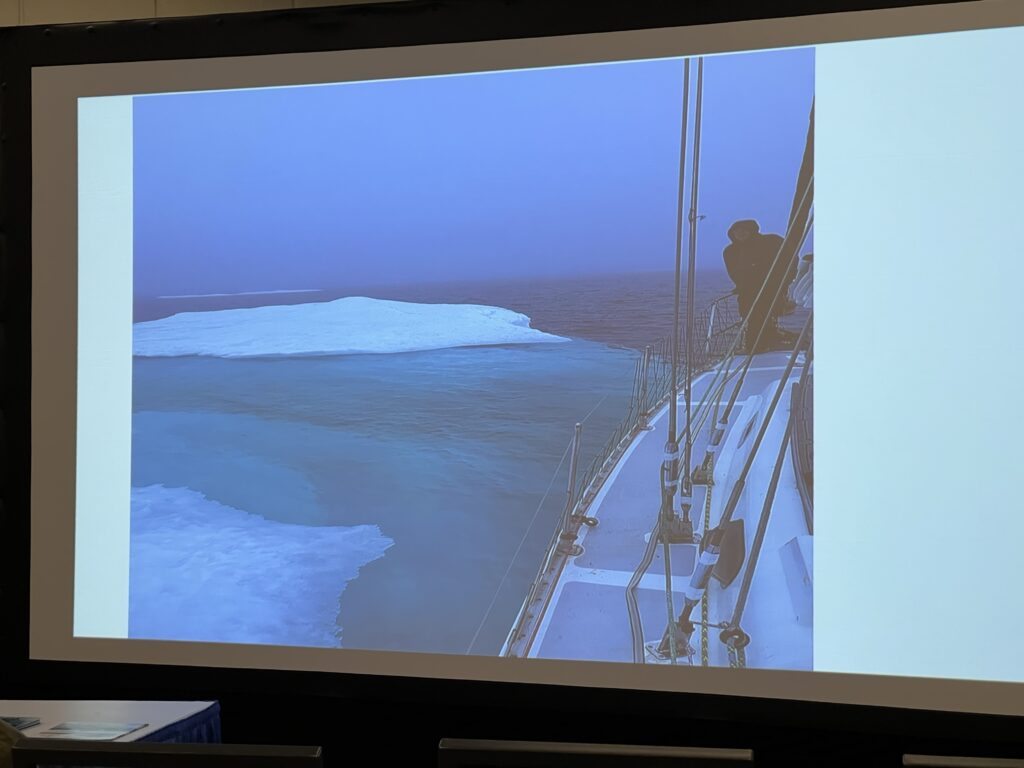

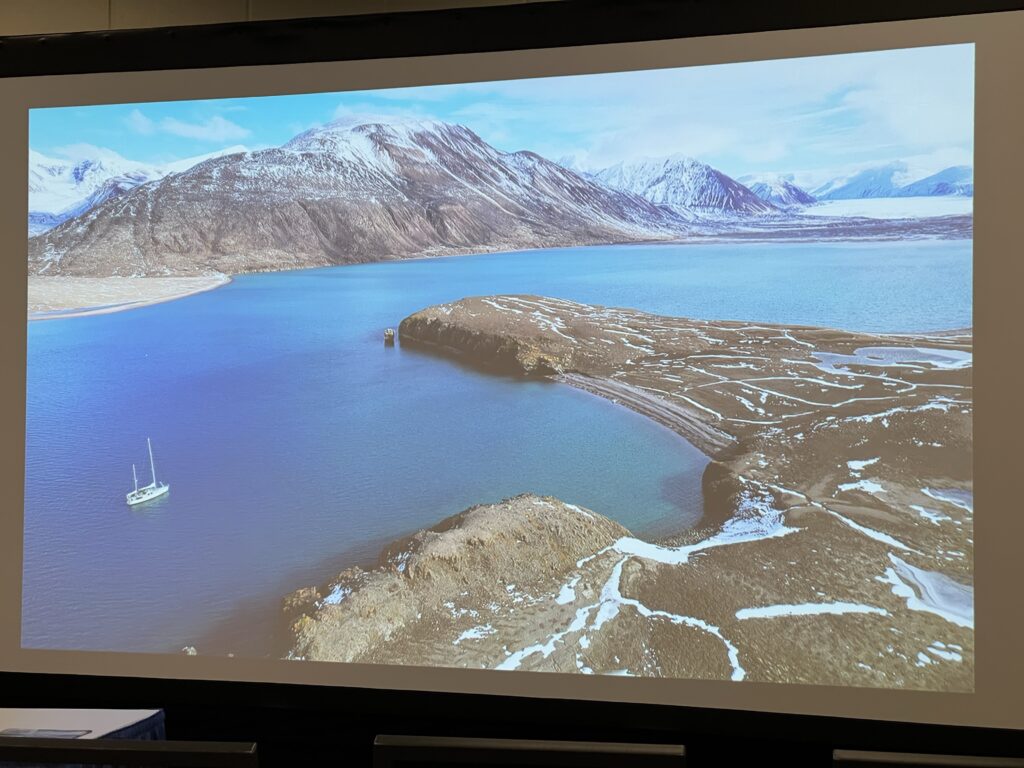

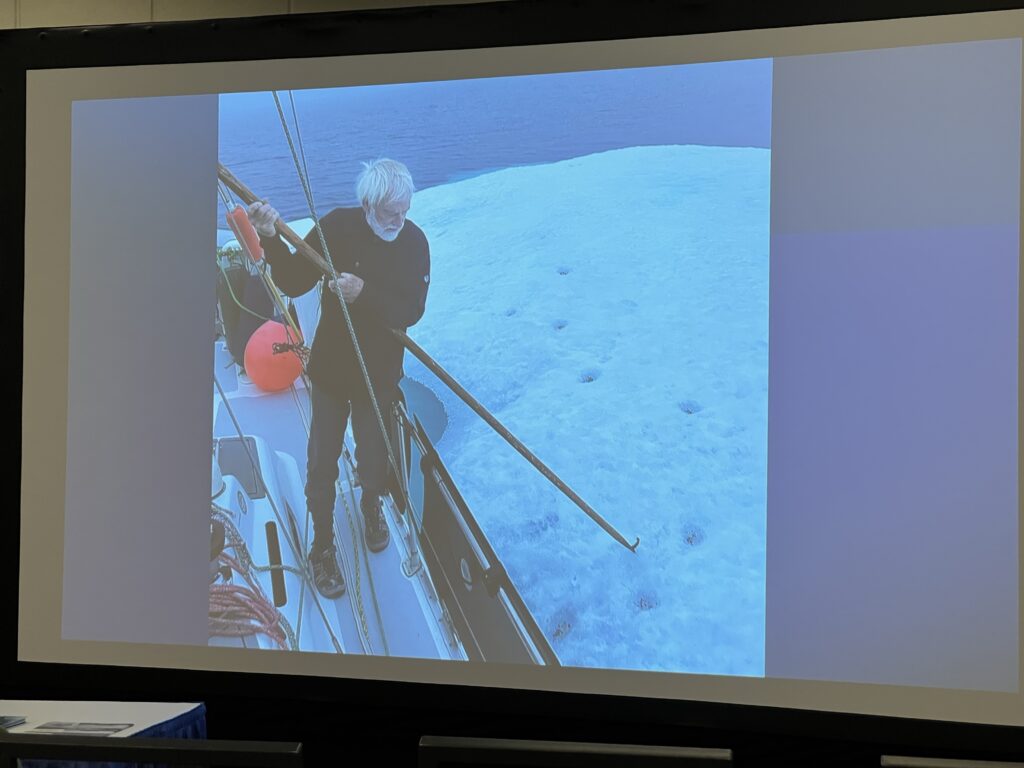

Anchoring rarely lasted all night. Ice from outside the coves used for anchoring, would inevitably threaten, requiring crew to move to a new ice free location.

The first experience anchoring with ice resulted in a berg attaching itself to One Ocean. From then on crew moved the vessel when ice bergs approached.